Scientists’ reactions to House Science Committee hearing

Here is a list of scientists’ comments in reaction to statements made during the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology hearing held on March 29th. [A more complete list of comments can be found here.]

“there is disagreement among scientists as to whether human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases is the dominant cause of recent warming, relative to natural causes” [Judith Curry]

Timothy Osborn, Professor, University of East Anglia, and Director of Research, Climatic Research Unit:

This is incorrect: assessments of the cause of recent warming consistently find that greenhouse gases are the dominant cause of recent warming. These assessments consider other climate forcings, including natural effects (the most important ones on timescales of decades are variations in solar and volcanic activity) and human-caused aerosols, but the most likely effect of these other forcing would have been to cause global cooling in recent decades. Thus, there is agreement between scientists that the observed warming is due to human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases.

“It is an empirical fact that the Earth’s climate has warmed overall for at least the past century. However, we do not know how much humans have contributed to this warming and there is disagreement among scientists as to whether human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases is the dominant cause of recent warming, relative to natural causes” [Judith Curry]

Gavin Schmidt, Director, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies:

There is indeed overwhelming evidence for warming in the last century. Curry’s claim that no one knows the attribution of this to human impacts is not a valid description of the state of knowledge. There are indeed plenty of studies that use statistical or model-based fingerprints to assess this and they overwhelmingly find a dominance of human activities over natural forcings or internal variability. For the more recent period (1950 onwards) the claims are even stronger—that effectively all the warming is caused by human activity with only a ~10% uncertainty due to internal variability. One can always find something to disagree with in such a statement, but disagreement in the absence of any quantitative result to the contrary is not worth much. Curiously, the paper that Curry cites to claim a low sensitivity (Lewis and Curry, 2015) assumes that all the warming is human caused.

“Current global climate models are not fit for the purpose of attributing the causes of recent warming or for predicting global or regional climate change on timescales of decades to centuries, with any high level of confidence.” -Judith Curry

Reto Knutti, Professor, ETH Zürich:

This statement is at odds with just about every detection and attribution study, every climate model, and basic physical principles of the global energy budget. The trend in natural forcing (solar and volcanic) from about 1950-2000 is nearly zero and can therefore not explain the observed warming. Natural variability is much smaller than the observed warming. In a recent study* we showed that “even if models were found to underestimate internal variability by a factor of three, it is extremely unlikely that internal variability could produce a trend as large as observed.” This leaves anthropogenic forcings as the main drivers, and we understand why: it is the physics of the greenhouse effect, which have been known for more than a century.

In terms of projections, confidence is high for large scale temperature trends, ocean acidification, or sea level rise over multiple decades, but of course lower for other local impact-relevant quantities. But the fact is that even projections made decades ago with much simpler models were remarkably accurate*.

As Kevin Trenberth and I argued in a recent post, an important question to me is whether as a society we are better off with imperfect predictions than with no predictions at all. If we absolutely want to go down a potentially likely path, it would be smarter to have an imperfect map than no map at all.

- Huber and Knutti (2012) Anthropogenic and natural warming inferred from changes in Earth’s energy balance, Nature Geoscience

- Stouffer and Manabe (2017) Assessing temperature pattern projections made in 1989, Nature Climate Change

- Fischer and Knutti (2016) Observed heavy precipitation increase confirms theory and early models, Nature Climate Change

- Allen et al (2013) Test of a decadal climate forecast, Nature Geoscience

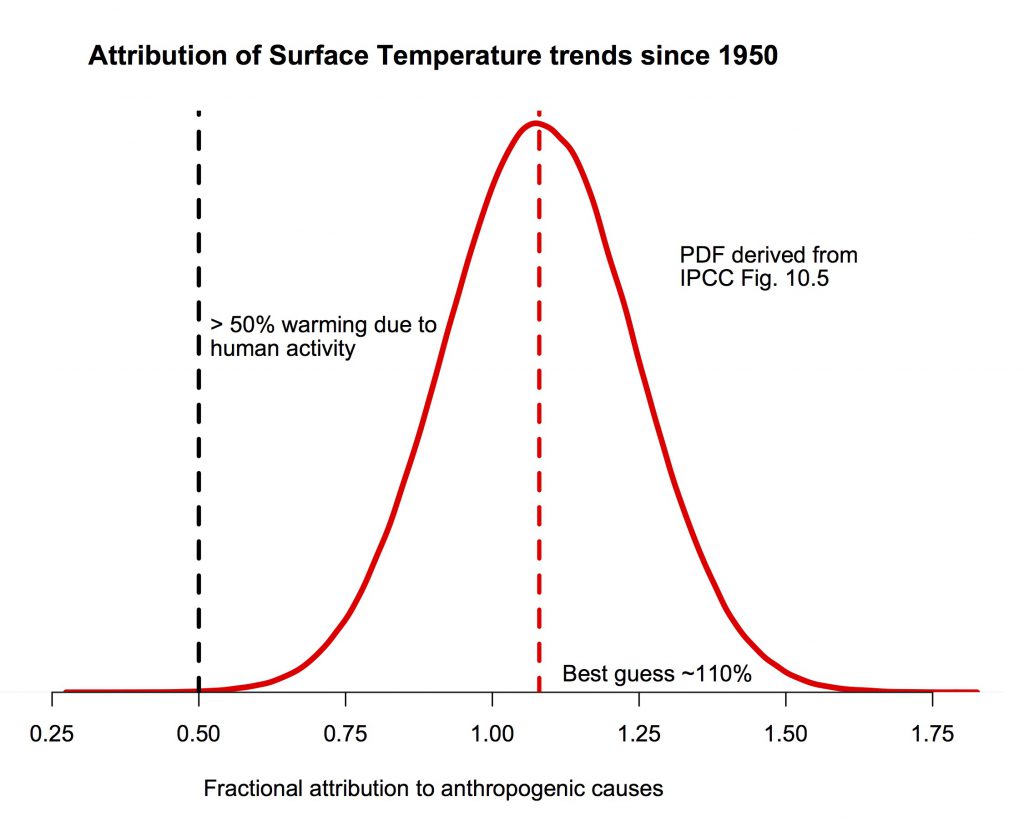

“And even the IPCC says more than half. That’s from 51 percent to 99 percent. That is a big interval… I just don’t know how much is human vs. how much is natural and I think there is a great deal of uncertainty and it is very difficult to untangle it” -Judith Curry

Timothy Osborn, Professor, University of East Anglia, and Director of Research, Climatic Research Unit:

Judith Curry’s interpretation of the IPCC’s assessment as meaning a range from 51 to 99 percent is incorrect. First, the range extends beyond 99 percent, because natural influences may have offset some of the warming from human activity. Second, because it suggests a uniform likelihood within that interval whereas the likelihood that the real contribution is near the edges of the range (i.e., as low as 51 percent of the observed warming or as much as one and a half times the observed warming).

There is indeed a great deal of uncertainty, but the IPCC assessed range takes this into account—by quantifying those uncertainties than can be quantified, and by making a broader, more conservative range to account for those that can’t be quantified.

“the models are simply too sensitive to the extra greenhouse gases that are being added to both the model and the real world.” [John Christy]

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

John Christy provides no evidence that the discrepancy is due to the models and not due to errors in his dataset; see below. Or due to errors in the comparison.

Even if the reason were the climate models themselves, his claim that models are thus too sensitive to greenhouse gases is a second step into evidence-less territory. Without given any evidence for it, Christy seems to assume that the reason cannot be any other factor such as the historical increases in small airborne particles (aerosols) or historical land-use changes or how much the ocean delays warming.

James Renwick, Professor, Victoria University of Wellington:

Misleading. There is a range of sensitivity to greenhouse gases [among models], some probably too insensitive and some likely overly sensitive. The distribution of model sensitivities lines up well with our understanding based on the paleoclimate record and other estimates.

Mark Zelinka, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:

Actually there are many plausible reasons why the models tend to simulate more warming during this period, and one cannot point unambiguously toward this one explanation (model climate sensitivity errors). Among the plausible reasons are (1) their temperature fluctuations due to internally-generated variability are not synchronized with those in nature because they are freely evolving coupled simulations (e.g., El Nino events will not occur at the same time in these simulations as they did in reality, nor are the phases of decadal modes of variability in models required to track those in nature), and (2) that the external radiative forcing applied to models was systematically overestimated, which has been demonstrated to be partly caused by the neglect of cooling induced by increased stratospheric sulfate aerosols from a series of moderate volcanic eruptions post-2000 (Santer et al 2014*), as well as errors in the treatment of recent changes in solar irradiance (Kopp and Lean 2011*), stratospheric water vapor (Solomon et al. 2010*) , stratospheric ozone (Eyring et al. 2013*), and anthropogenic aerosols (Shindell et al. 2013*).

In fact, recent studies (Santer et al 2014*, Huber and Knutti 2014*) suggest that the model-observation discrepancy is very unlikely to be caused by model sensitivity errors, in contrast to Dr. Christy’s claim. For example, Huber and Knutti (2014)* note “…recent claims of much lower climate sensitivities and future warming seem much less plausible. We show that the reduced warming and mismatch between models and observations since about 1997 or 1998 can, to a large extent, be explained by the combined effect of reduced forcing and natural variability, each of these components contributing about an equal amount.”

- Santer et al (2014) Volcanic contribution to decadal changes in tropospheric temperature, Nature Geoscience

- Kopp and Lean (2011) A new, lower value of total solar irradiance: Evidence and climate significance, Geophysical Research Letters

- Solomon et al (2010) Contributions of Stratospheric Water Vapor to Decadal Changes in the Rate of Global Warming, Science

- Eyring et al (2013) Long-term ozone changes and associated climate impacts in CMIP5 simulations, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres

- Shindell et al (2013) Radiative forcing in the ACCMIP historical and future climate simulations, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics

- Huber and Knutti (2014) Natural variability, radiative forcing and climate response in the recent hiatus reconciled, Nature Geoscience

A growing body of evidence* indicates the exact opposite [of Dr. Christy’s claim]—that low-level cloud coverage (which largely determines this planetary heating effect) tends to decrease with warming in observations, and that the models that agree best with observations are those who predict stronger-than-average decreases in low-level cloud cover with future warming. Though far from being settled, the growing evidence lines up against Dr. Christy’s claims.

- Sherwood et al (2014) Spread in model climate sensitivity traced to atmospheric convective mixing, Nature

- Qu et al (2015) Positive tropical marine low-cloud cover feedback inferred from cloud-controlling factors, Geophysical Research Letters

- Zhai et al (2015) Long-term cloud change imprinted in seasonal cloud variation: More evidence of high climate sensitivity, Geophysical Research Letters

- Brient and Schneider (2016) Constraints on Climate Sensitivity from Space-Based Measurements of Low-Cloud Reflection, Journal of Climate

- Myers and Norris (2016) Reducing the uncertainty in subtropical cloud feedback, Geophysical Research Letters

- McCoy et al (2017) The change in low cloud cover in a warmed climate inferred from AIRS, MODIS and ECMWF-Interim reanalysis, Journal of Climate

“There is little scientific basis in support of claims that extreme weather events – specifically, hurricanes, floods, drought, tornadoes – and their economic damage have increased in recent decades due to the emission of greenhouse gases. In fact, since 2013 the world and the United States have had a remarkable stretch of good fortune with respect to extreme weather, as compared to the past.” [Roger Pielke Jr]

Kerry Emanuel, Professor of Atmospheric Science, MIT:

Most of the published scientific work concerns the expected response of tropical cyclones to climate change and anticipates that such storms will become stronger and perhaps less frequent, but at a rate that should not be formally detectable until mid-century. Yet there is clear satellite-based evidence (e.g. Elsner et al., Nature, 2008; Kossin et al. J. Climate, 2013)* of increasing incidence of the strongest storms, as theory dating back to 1987 predicted.

- Elsner et al. (2008) The increasing intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones, Nature

- Kossin et al. (2013) Trend Analysis with a New Global Record of Tropical Cyclone Intensity, Journal of Climate

James Elsner, Professor, Florida State University:

While there is little scientific evidence that there will be more (or fewer) hurricanes or more hurricanes hitting the U.S., there is strong theoretical and statistical evidence that the strongest hurricanes are getting stronger as the oceans heat up due to global warming from the emission of greenhouse gases. In fact, there is statistical evidence that the magnitude of economic damage in the U.S. from hurricanes increases with rising ocean temperature.

- Elsner, J. B, J. P. Kossin and T. H. Jagger (2008). “The increasing intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones”. In: Nature 455.7209, pp. 92-95

- Elsner, J. B. (2007b). “Granger causality and Atlantic hurricanes”. In: Tellus A 59.4, pp. 476-485.

- Jagger, T. H, J. B. Elsner and R. K. Burch (2011). “Climate and solar signals in property damage losses from hurricanes affecting the United States”. In: Natural Hazards 58.1, pp. 541-557.

“they added that if there was a slight or modest global warming that the sea levels would fall not rise” [Mo Brooks]

Matt King, Professor, University of Tasmania:

This is incorrect. Warming has been occurring through the 20th century and glaciers around the world, plus Greenland, have been melting. Further melting in the future will see a substantial further reduction in glacier and ice sheet mass, most of which will end up in the ocean and produce sea level rise.

Andrea Dutton, Visiting Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin:

This summary is not correct. The data clearly show that even with the amount of global warming that we have already experienced, that the global mean sea level has risen. The amount of snowfall over Antarctica is not enough to balance this effect of the seas rising, which itself is a function of seawater expanding as it heats up as well as the addition of meltwater from mountain glaciers and polar ice sheets (IPCC, AR5).

“I have demonstrated that we cannot predict the behavior of climate.” -John Christy

Timothy Osborn, Professor, University of East Anglia, and Director of Research, Climatic Research Unit:

This statement is incorrect: there are multiple examples where we have predicted the behaviour of climate, ranging from the seasonal cycle, the response to volcanic forcing, the warming of recent decades to some palaeoclimatic changes. See: Schmidt and Sherwood (2015)*

It is unfortunate that John Christy dramatically overstates the implications of his comparison between model simulations and tropical tropospheric temperatures to imply that we can make no predictions, because this is an important challenge for testing climate models from which we can learn much about climate response and about how to evaluate confidence in models. But his demonstration has flaws in its presentation (e.g. using too short a baseline period) and distracts from the key information about how models and observational trends differ in this region. See Santer et al. (2017)* for a comparison and an assessment of the implications — there are differences in simulated and observed warming trends in this part of the atmosphere but they are much less than Christy claims and don’t support a blanket assertion that “we cannot predict” climate.

- Schmidt and Sherwood (2015) A practical philosophy of complex climate modelling, European Journal for Philosophy of Science

- Santer et al (2017) Comparing Tropospheric Warming in Climate Models and Satellite Data, Journal of Climate

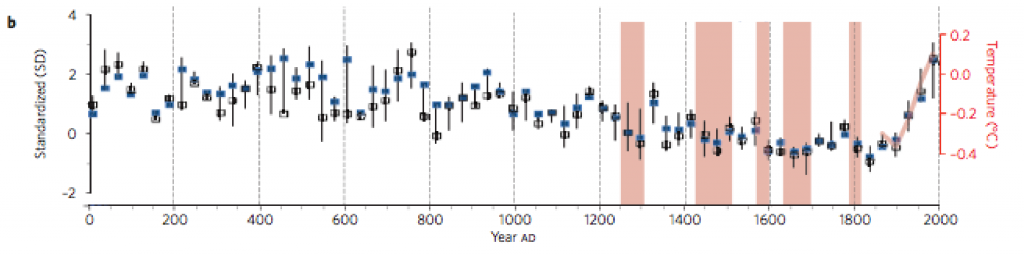

“It’s been warming for hundreds of years! And we can’t explain all of that due to human causes..” -Judith Curry

Valerie Trouet, Associate Professor, University of Arizona:

The first sentence is a very general statement (what is “it”?), but I’m assuming Dr. Curry means Northern Hemisphere, Southern Hemisphere, or global average temperatures. None of these have been warming for hundreds of years, as she claims, but the available proxy data show a warming since approximately 1850 (see Fig. 5.7 in IPCC AR5 and Fig. 4b in PAGES2Kconsortium, 2013*, below). These results are based on paleoclimate data, not on models.

Figure – Composite temperature reconstructions: Standardized 30-year-mean temperatures averaged across all seven continental-scale regions. The red line is the 30-year-average annual global temperature from the HadCRUT4 instrumental time series relative to 1961–1990.

As to Dr. Curry’s 2nd statement, no one claims that all past warming is due to human causes. More important, however, is that the warming since 1850 cannot be explained by natural climate variability alone, without human causes. Only by including anthropogenic CO2 emissions as a forcing (in addition to the other external forcings) can models replicate the recent warming that is shown in the data.

- Pages 2k Consortium (2013) Continental-scale temperature variability during the past two millennia, Nature Geoscience