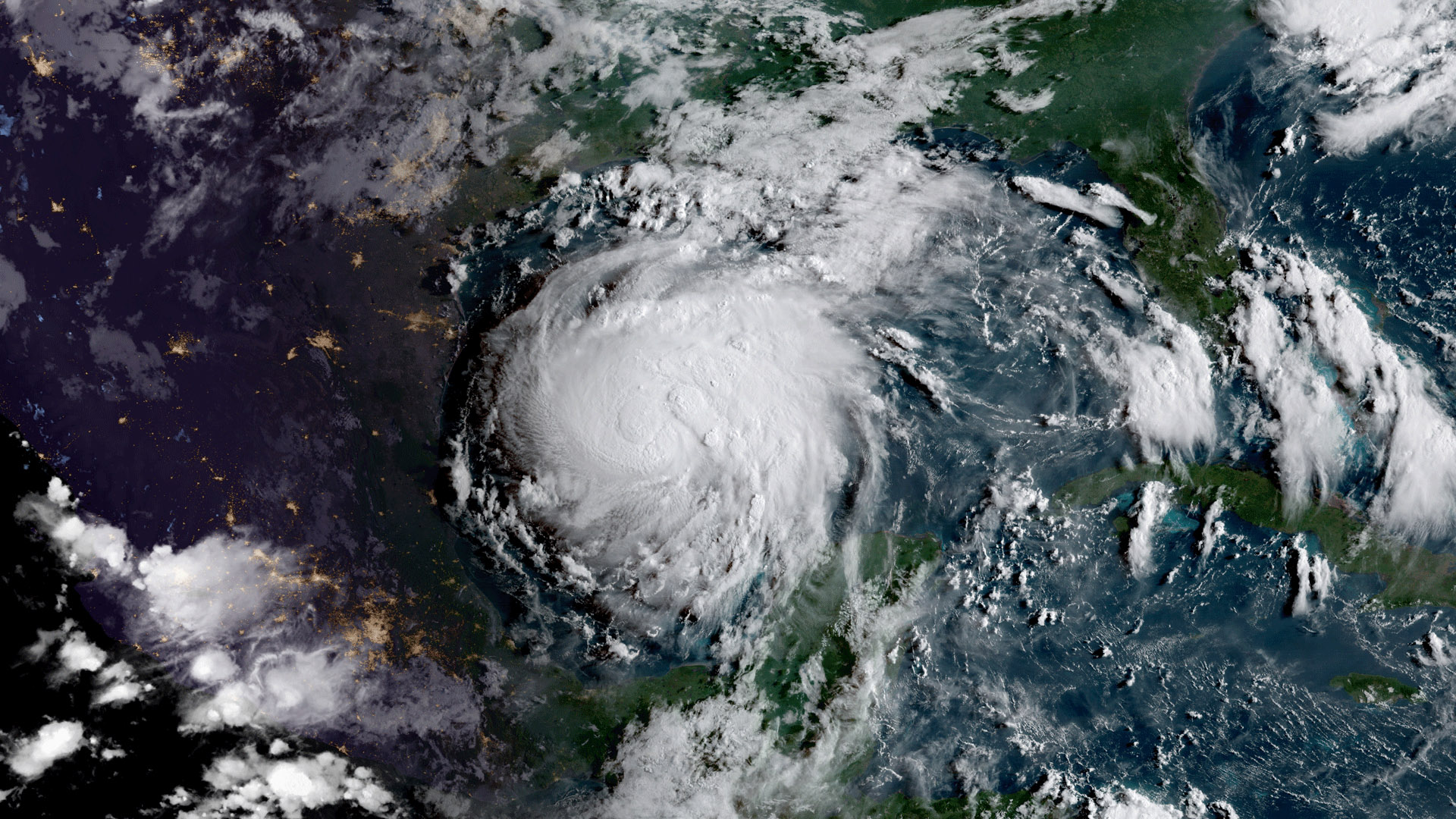

On November 13th, MIT climate scientist Kerry Emanuel published a study estimating the probability of Hurricane-Harvey-like rainfall events for today’s climate and for a future, warmer climate. The study concluded that while there was only about a 1% chance of such a storm hitting Texas in any given year in the 1980s and 1990s, the probability could increase to about 18% by the end of this century if greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase as they have in the past.

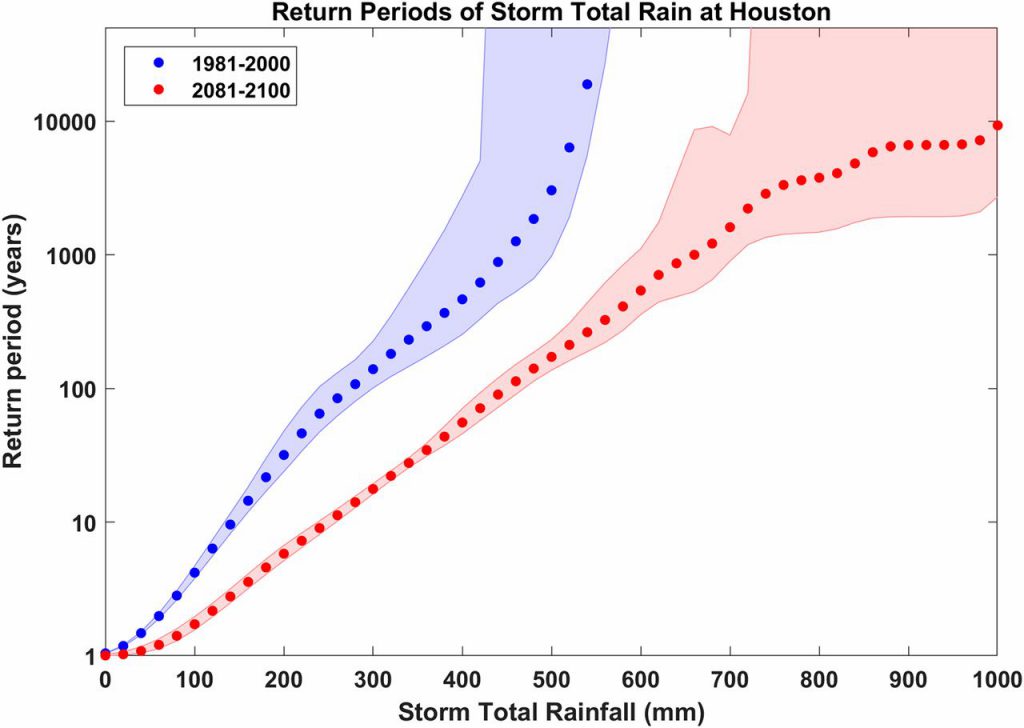

Figure – Return periods of hurricane total rainfall (millimeters) at the single point of Houston, Texas, based on 3,700 simulated events each from six global climate models over the period 1981–2000 from historical simulations (blue), and 2081–2100 from RCP 8.5 simulations (red). The dots show the six-climate-set mean and the shading shows 1 standard deviation in storm return periods. Source: Emanuel (2017).

For example: a 500 mm rain event in Houston is an event that has a probability to occur once in 1000 years in the current climate, but once in 100 years in a warmer climate.

The next day, an article at The Daily Caller criticized the study, claiming that it could draw no conclusions about human contributions to Harvey’s rainfall because it didn’t analyze the blocking high pressure systems that stalled the storm over Houston for days.

On November 20th, an op-ed written by US Congressman Lamar Smith (R-TX) was published by The Daily Caller under the headline “BAD SCIENCE: An MIT Study Linking Hurricane Harvey Rainfall To Climate Change Is Alarmist Bunk”. The op-ed praises The Daily Caller’s article, which Smith says “rightly exposes the major flaws in a newly-published Massachusetts Institute of Technology climate change study”.

Rep. Smith’s op-ed contains a number of misleading claims about the study as well as the relationship between climate change and weather extremes. Rep. Smith selects very specific statements about weather extremes to argue that climate change has played no role. But this ignores a great deal of evidence and research on various extremes, which does show a significant influence on certain types of weather.

Rep. Smith thinks that “The MIT study attempts to attribute rainfall during Hurricane Harvey to climate change.” But this is not what the study does. It does not study the influence of climate change on Harvey’s rainfall per se, but the probability of an event that brings as much precipitation as Harvey. The study states this clearly in its abstract: “We estimate, for current and future climates, the annual probability of areally averaged hurricane rain of Hurricane Harvey’s magnitude.” And the study finds that hurricane-related rainfall events of this magnitude are expected to become more frequent if the climate warms further.

In one misleading statement, for example, Rep. Smith writes, “Hurricane Harvey was portrayed in the media as a deadly consequence of a warming climate. However, the facts are that this just isn’t the case. When looking at historical data for hurricanes affecting the United States, the data shows no trend over time.”

Purdue University Assistant Professor Dan Chavas examined Smith’s statement:

Our historical record is very short, especially for rare events such as the extreme rainfall induced by Harvey. As a result, it is hard to understand the effects of climate change on these events by looking at historical data alone. More specifically, determining how climate change will alter the impacts of hurricanes that make landfall requires thinking not only about how frequently a storm makes landfall in the U.S. but also how severe the hazards associated with each storm—wind, storm surge, rainfall-induced flooding—will change. In the case of Harvey, the extreme rainfall was the result of a mix of factors occurring together: a very intense storm that remained nearly stationary for multiple days near the coastline near Houston. This situation allowed Harvey to continuously evaporate incredible amounts of water from the Gulf of Mexico and then rain all of that water out over nearly the same place for multiple days in a row. This study uses a clever method to capture all of these factors in order to calculate how climate change may increase the frequency of these extreme rainfall events in the Houston area.

Prof. Kerry Emanuel also explained that Smith’s claim is misleading:

Congressman Smith is an expert at using seemingly true statements to convey falsehoods. With any sufficiently rare event, by its very definition, there are not enough historical data to detect trends within traditional confidence bounds. The inability to detect a trend in noisy, short historical records cannot be interpreted as evidence for the absence of such a trend.

Similarly, signal detection should not be confused with risk assessment. My paper was explicitly a modeling study, using quite a few different models and reanalyses to estimate current and future tropical cyclone flood risk in Texas. It is entirely consistent with the other studies and with the IPCC in predicting an increased incidence of high intensity tropical cyclones, and greatly enhanced tropical cyclone rainfall. As far as I can tell, the latter is a universal consensus of those who study the effect of climate change on tropical cyclone.

Rep. Smith’s op-ed also claims that “[F]looding has been found to have no correlation to climate change. Even the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found in its latest report that there is a lack of scientific evidence pertaining to floods and thus it has low confidence regarding any trends in magnitude or frequency of floods on a global scale.”

By focusing on all types of flooding in all regions of the world, Smith misrepresents the scientific understanding of this topic. The latest IPCC report did find a likely increase in the frequency of intense rainfall events, for example, and projected that this trend should continue as the world warms.

As Dan Chavas notes, Smith’s claim also ignores the content of Emanuel’s study:

This statement correctly highlights how it can be difficult to use the historical record to attribute historical trends in floods to climate change. However, this is for floods in general, which are usually not caused by hurricanes but rather are caused by a combination of more complex factors related to persistent rainfall patterns over multiple days or weeks in a given region. Here this study focuses specifically on shorter-term extreme rainfall associated with hurricanes, which are isolated events with clear start and end times. This study exploits our collective scientific understanding of hurricanes to examine extreme rainfall events produced by hurricanes and how the frequency of these events may change at a given location in a future, warmer climate.

As Climate Feedback reviewers pointed out in an August claim review related to Harvey, the warming of the ocean and atmosphere increases the moisture-holding capacity of the air. This can boost the rainfall totals of storms like Harvey, which lift tremendous amounts of water vapor from the ocean and later drop it as rain.

In his op-ed, Rep. Smith writes, “Scientists should look to trends before making dire predictions about extreme weather, but the trends show no link to climate change.” Scientists do study weather trends, of course, as well as the physics behind them. Smith simply misrepresents what they have discovered. Rep. Smith concludes the study is bunk without any careful analysis, which indicates his conclusion is likely more a reflection of his wish to reject scientific findings that conflict with his opinion than a dispassionate analysis of the evidence.