Misleading: Research unambiguously shows that the net effect of continued climate change this century—factoring in both positives and negatives—is significant harm to humans and the rest of Earth’s ecosystems.

Misrepresents the scientific process: Scientists do not simply assume that warming has dangerous consequences. This is a careful conclusion derived from extensive research.

Pruitt’s claim that the human contribution to global warming is unclear was evaluated in a previous Claim Review and found to be incorrect.

REVIEW

CLAIM: [N]o one disputes that climate changes, is changing. We see that, that’s constant. We obviously contribute to it, we live in the climate, right? So our activity contributes to the climate change to a certain degree. Now measuring that with precision, I think, is more challenging than is let on at times.

But I think the bigger question is what you ask at the very end: Is it an existential threat? Is it something that is unsustainable, or what kind of effect or harm is this going to have? We know that humans have most flourished during times of, what, warming trends. I think there are assumptions made that because the climate is warming, that that is necessarily a bad thing. Do we really know what the ideal surface temperature should be in the year 2100? In the year 2018? That's fairly arrogant for us to think we know exactly what it should be in 2100.

Wolfgang Cramer, Professor, Directeur de Recherche, Mediterranean Institute for Biodiversity and Ecology (IMBE):

“We know that humans have most flourished during times of, what, warming trends.”

It is not clear which times Mr. Pruitt refers to and what exactly he refers to as “flourishing”. From scientific studies, no “time of warming” comparable to current warming is known during human history. There is therefore no basis to ignore the numerous formal impact and risk analyses that have been made by scientists in relation to current and expected climate change.

“I think there are assumptions made that because the climate is warming, that that is necessarily a bad thing.”

There is no basis to qualify the scientific assessment of climate change and its impacts as “assumptions”. Scientific impact studies from all around the world have permitted the IPCC, under maximum scrutiny by government-nominated experts, to conclude that, “In recent decades, changes in climate have caused impacts on natural and human systems on all continents and across the oceans. Evidence of climate-change impacts is strongest and most comprehensive for natural systems. Some impacts on human systems have also been attributed to climate change, with a major or minor contribution of climate change distinguishable from other influences.” For a detailed elaboration of those impacts, observed and expected in the future, Mr Pruitt is invited to take notice of the full Fifth Assessment Report by the IPCC Working Group II*.

“Do we really know what the ideal surface temperature should be in the year 2100? In the year 2018? That’s fairly arrogant for us to think we know exactly what it should be in 2100.”

The concept of an “ideal surface temperature” would require some elaboration. Clearly, temperatures differ widely across the globe, through the seasons, through the day and night cycle, and also between years. As detailed analyses show, practically all systems essential for human life support are adapted to certain ranges in temperature and water availability. While these may differ between regions, they have in common that departure from these ranges by several degrees C often destabilizes the system. Two degrees of warming are known to lead to, among other things, massive glacier loss and substantial sea-level rise. It is a certainty that coastal infrastructures and the livelihoods of people living near the world’s coasts would be massively impacted by such sea-level rise. From this it follows that it is not a matter of arrogance to consider the current climate more suitable for human well-being on the planet than one that differs from current conditions by several degrees C.

William Anderegg, Associate Professor, University of Utah:

“Humans have most flourished during warming trends”

This is deeply misleading. Human civilization has arisen in the relatively stable climate of the past 10,000 years. The rate of warming is absolutely critical for the impacts on human society and the current rate of warming vastly exceeds rates of warming anytime during human civilization and likely the past several million years1.

“Because the climate is warming, is that necessarily a bad thing…”

Scientists are incredibly confident that the current rate of warming is indeed a bad thing with a large amount of costly and dangerous impacts for society. In 2017 alone, the US spent more than $300 billion coping with disasters, many of which were supercharged by climate warming. Future projections indicate that the costs of climate change will be high—more heatwaves, more droughts, major agricultural risks, sea level rise, species losses2. If Pruitt cares about the evidence and input from scientists, the answer is simple—yes, it’s a bad thing, a very bad thing.

- 1-Diffenbaugh and Field (2013) Changes in Ecologically Critical Terrestrial Climate Conditions, Science

- 2-IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report

Peter Neff, Assistant Research Professor, University of Minnesota:

“I think you are right, no one disputes that climate changes, is changing. We see that, that’s constant.”

Climate change is not constant: anthropogenic climate change represents a significant and concerning departure from natural climate variability.

Mr. Pruitt is misrepresenting our understanding of past climate, which is built on the efforts of thousands of Americans who work to develop paleoclimate records (not to mention the multitude of international efforts). This represents not only scientists, but people of all trades and backgrounds who support our institutions, local communities, and remote fieldwork. See evidence of the monumental effort behind one of these records, the WAIS Divide Antarctic ice core, here.

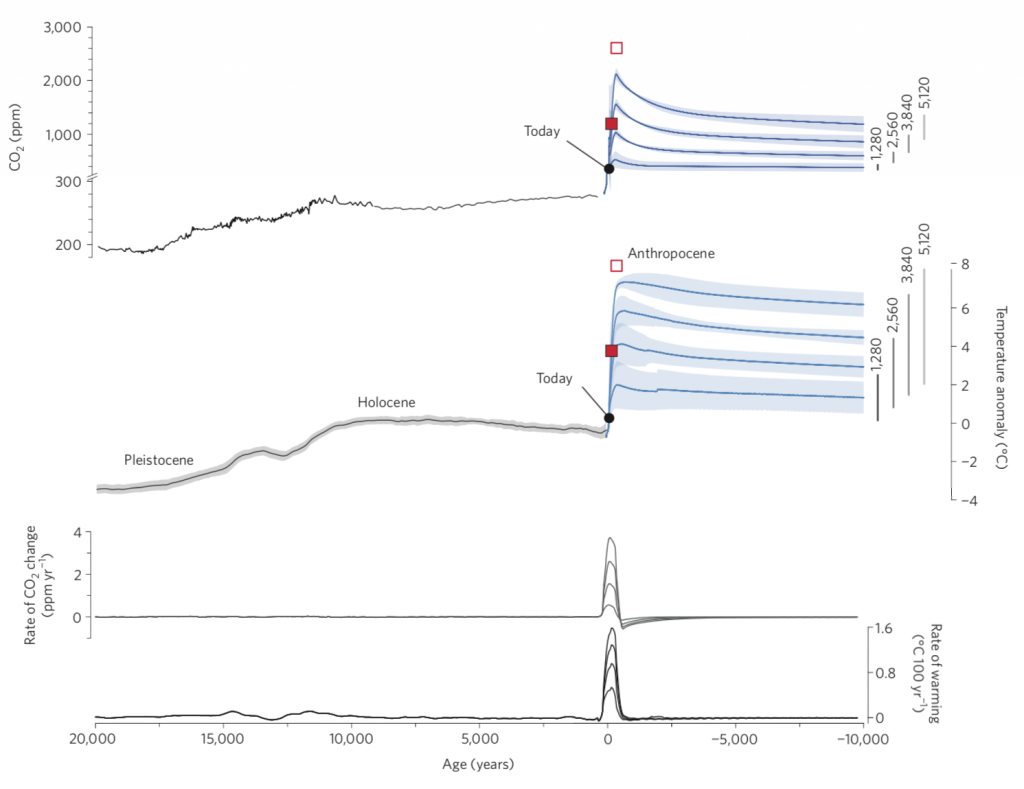

CO2 is rapidly increasing relative to what we know from records of the past, the best examples from my area of expertise being polar ice cores. Before the 1970s, CO2 growth rate in the atmosphere (how much CO2 is added to the atmosphere per year) had not exceeded 1 part per million (ppm) per year in more than 20,000 years (see figure below). But I will limit this response to that time period.

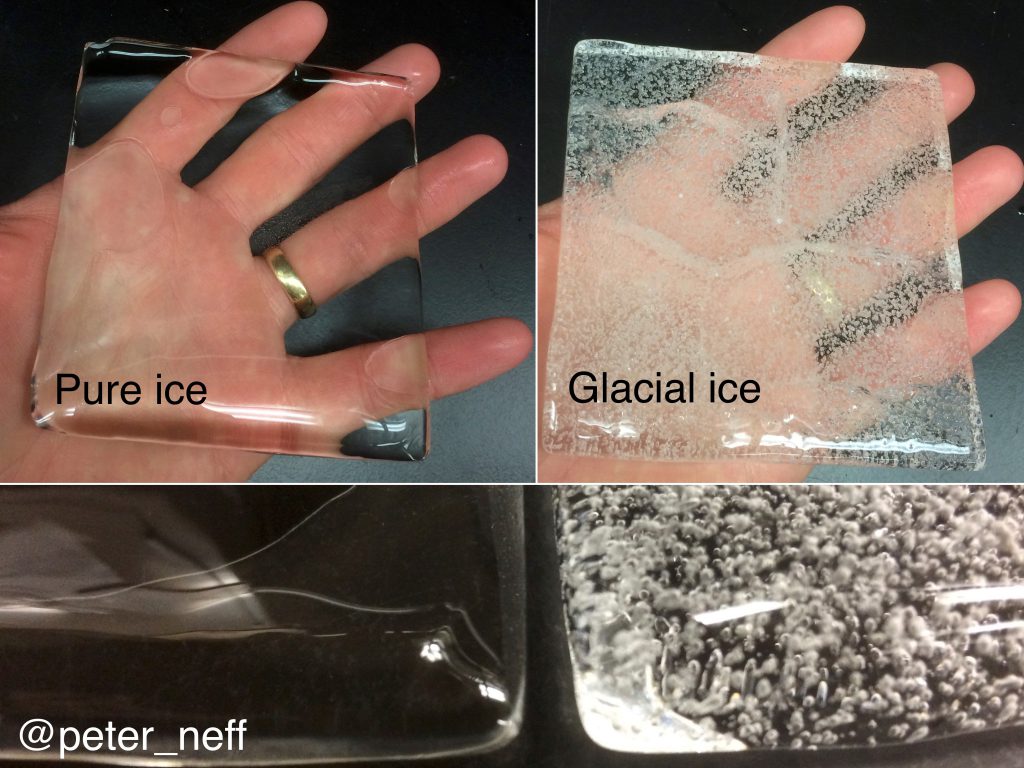

We can directly measure CO2 in the atmosphere today. Ice cores allow us to similarly directly measure atmospheric CO2 from the past, thanks to the fact that snowflakes trap air between their six feathery-fingers. As these fluffy flakes accumulate on the polar ice sheets—never melting—they are compressed by year after year of snowfall, trapping air in bubbles (see below, pure ice that my lab group made on the left, versus glacial ice from Antarctica on the right).

Clark et al*, in the figure above, shows high-resolution records of CO2 and temperature for the past 20,000 years from ice cores including the WAIS Divide ice core from West Antarctica, completed in 2013. They also show model projections of CO2 and temperature for 10,000 years into the future, and you can see the likely impact of anthropogenic greenhouse warming—it will be long-term. It also shows temperature reconstructions from these same records, and the rate of change in CO2 and temperature (bottom two panels).

These data (which are publicly available), demonstrate that anthropogenic CO2 increase and corresponding warming are highly significant and large departures from previous, natural climate change as seen in the WAIS Divide and other ice cores.

In comparison to past atmospheric composition from ice cores, modern CO2 is easy to measure. (See the Keeling Curve from Mauna Loa.)

The rate of CO2 increase—how much CO2 is added to the atmosphere each year—can be quantified from this. We’ve added more than 1 ppm of CO2 to the atmosphere per year since the 1970s. If that seems small to you, consider that 1 part per million of the Earth’s atmosphere is equivalent to 7.8 petagrams of CO2. That’s 1015 grams, or something like the mass of 50 million blue whales.

Before humans, this sort of atmospheric CO2 change and warming took hundreds or thousands of years.

“We obviously contribute to it, we live in the climate, right? So our activity contributes to the climate change to a certain degree. Now measuring that with precision, Gerard, I think, is more challenging than is let on at times.”

Mr. Pruitt is jumping to conclusions here; although it is a herculean effort to measure temperature change the world over, it is not the case that measurement uncertainty means temperature trends are not quantifiable and their causes not attributable.

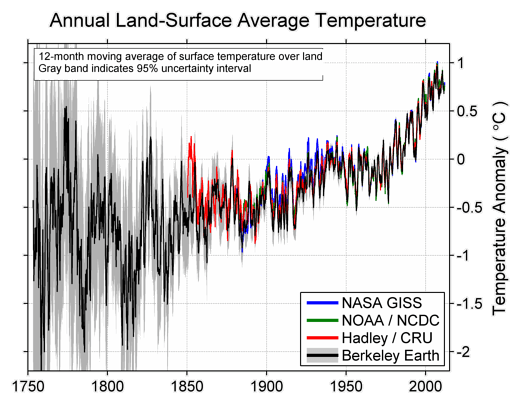

Measurement uncertainty is far smaller than the magnitude of the global average temperature change. Temperature is unequivocally increasing, with independent land and ocean temperature records all in agreement.

Berkeley Earth specifically set out to address bias in temperature records and only reinforced the data of NASA and the UK Hadley Center/CRU.

Source: Berkeley Earth

Attribution of this global temperature increase has been demonstrated ad nauseam. Without anthropogenic greenhouse gases (and slight cooling from anthropogenic soot aerosol emissions) you cannot reproduce the observed warming. One of the best interactive illustrations of this can be found via Bloomberg.

“I think there are assumptions made that because the climate is warming, that that is necessarily a bad thing.”

Briefly, Mr. Pruitt doesn’t do the full work here to cherry-pick why he thinks warming may be a good thing, but any cherry found is overwhelmed by the negative impacts of a warming climate. It is also irrelevant what exactly the temperature in 2100 is, but if that temperature is higher than it is today—and it virtually certainly will be higher—it will have negative impacts on our current societal arrangements, habits, resources, and so on.

For instance: a large percentage of the world’s population lives near the coast (on the order of 40%). The world is warming and will continue to warm unless we reduce greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. Maintaining the current sea level would require maintaining the land ice that is stored on the polar ice sheets, primarily Greenland and Antarctica (they store the equivalent of more than 200 feet of global sea level).

However, both of these ice masses are melting, adding to sea level. The rate of melting is accelerating in both cases. This has raised and will continue to raise sea level, leading to coastal inundation events like that recently observed in Boston, MA during the winter storm Grayson earlier this year. When storm surges coincide with high tide under higher sea level conditions, this will become more common.

This is only one example of why increased global temperatures are a bad thing for humans. Again, it is irrelevant what the exact temperature is in 2100.

- Clark et al (2016) Consequences of twenty-first-century policy for multi-millennial climate and sea-level change, Nature Climate Change

Kelly McCusker, Research Associate, Rhodium Group and Climate Impact Lab:

We know that humans flourished during times of stable climate—for example during the relatively stable climate of the Holocene (the last roughly 11,000 years), humans developed agriculture and settled into civilizations. The warming we are experiencing today is occurring at a much faster pace than anything we have seen in at least that time period*. The pace of change is extremely important for the ability for humans and ecosystems to adapt to rising temperatures. That assumes that adaptation is an option—poor nations do not have the resources to adapt properly. While there are some regions and sectors that could benefit from global warming (e.g. agricultural regions in Canada), the number of objectively negative impacts from projected warming are too numerous to exhaustively list, but include sea level rise wiping out coastal communities and causing economic damage, increased frequency of heatwaves and associated mortality, and many more.

- Marcott et al (2013) A Reconstruction of Regional and Global Temperature for the Past 11,300 Years, Science

Jennifer Francis, Senior Scientist, Woods Hole Research Center:

The issue is not just about warming, it’s about how fast it’s happening. In recent years the pace of warming has been unprecedented in the past thousands, if not millions, of years. When changes happen slowly, people and ecosystems can adapt. Not only is warming happening rapidly now, but costly extremes are increasing, as well, some of which are directly related to global warming: more severe heatwaves and droughts, heavy precipitation events, coastal flooding, and more intense tropical storms. The scientific evidence is unequivocal, but if you don’t allow facts to inform your thinking, then your beliefs will deviate from reality, which unfortunately seems to be the case for the director of our Environmental Protection Agency.

Is warming necessarily a bad thing? It’s not the average change that threatens society, it’s the extremes. Warming may be appreciated in places that are not already too warm and by people who have air-conditioning, but billions of people without air conditioning are being affected by extreme heatwaves beyond the human body’s ability to cool itself. Recent years have brought longer, hotter heatwaves that killed thousands (e.g. Russian heatwave of 2010, European heatwaves of 2003 and 2017) and these are expected to increase in both frequency and intensity. There’s nothing good about that.

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

Indeed humans have lived through periods of strong warming and cooling during pre-historic times. However, civilizations have developed only in the last ca. 10,000 years, coinciding with the beginning of a period with unusually stable climate (the Holocene1). In fact, this climate stability is usually identified as the key enabler of the development of human settlements, agriculture and animal domestication, labour division and trade… civilisation. The rates of increase of greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere (and consequent warming) have no precedent in the past 20,000 years. Human emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases are thus changing the energy imbalance of the planet at a rate never experienced by civilizations.

The ten hottest years since 1880 were all registered after 1998. An increasing number of record-breaking extreme events (heatwaves, floods, droughts, hurricanes, wildfires) has been registered, with high death tolls and devastating costs for the economy and ecosystems2. There is evidence that the likelihood of occurrence of many of these events has increased due to the warming registered in the past decades (global annual average surface temperature reached 0.94 °C in 2016). The frequency and intensity of such extremes is expected to increase with future warming, imposing severe human and environmental costs. Defining targets for additional future warming is responsible, rather than arrogant. This allow us to collectively define measures to mitigate or adapt to the damaging impacts of climate change, protect our societies and the environment.

- 1-Petit et al (1999) Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica, Nature

- 2-Coumou and Rahmstorf (2012) A decade of weather extremes, Nature Climate Change

Alek Petty, Postdoctoral associate, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center:

The rapid rate of warming we’re currently experiencing makes it extremely challenging for ecosystems to adapt to this changing climate. Increases in global temperatures are also associated with increases in extreme weather events, (e.g. heatwaves, droughts, storms, hurricanes) which result in huge costs to society. Our sea levels are also rising as the oceans warm and the ice sheets melt at alarming rates. This is all primarily driven by human emissions of greenhouse gases. Decisions made now will determine the future evolution of our climate system and it’s imperative that policy makers are aware of the overwhelming negative consequences of continued greenhouse gas emissions.

“We obviously contribute to it, we live in the climate, right? So our activity contributes to the climate change to a certain degree.”

This seems to be a new tactic of climate denialism, agree that we are contributing to climate change while making it seem like this is not a big deal. Unfortunately, it’s with high confidence that we know that the ~1.5 degrees F of warming we’ve had over the last century or so is due to human caused increases in greenhouse gases. This article in Bloomberg provides probably the best primer on this.

Ken Caldeira, Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science:

There is no time in the history of human beings on this planet when temperatures have increased as much and as rapidly as temperatures are projected to increase under future “business-as-usual” greenhouse gas emission scenarios.

The suggestion that global warming will cause humanity to flourish runs counter to what we know about heat stress in the already warm tropics. Nevertheless, it is possible that cold countries like Russia and Canada could ultimately benefit from global warming.

One might consider the assumption that it is OK to conduct an irreversible global scale experiment on our planet’s climate system without the buy-in of affected parties to be a bit “arrogant”. One would think that humility might counsel taking a “first do no harm” approach.

Climate change is not an existential threat to humanity at large, but it is an existential threat to people and communities whose existence is threatened by crop failures, severe storms, and/or sea-level rise.

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

Firstly, Scott Pruitt’s first point (about humans flourishing during warming) for me is a real left-field notion. I haven’t heard of a study that supports this, and to be frank I can’t even imagine where this idea has come from. For me, this is at best ill-informed and at worst downright lying. The only example I can think of that he is referring to is the warming going into the Medieval Warm Period, beginning around 800AD until it peaked at around 1000AD. Except perhaps for the Vikings, flourishing on the coasts of Greenland, or if you are a particularly big fan of smallpox, I can see very little evidence that would make this an outstanding period in terms of humankind “flourishing”. Indeed, historically, this period has fallen by most definitions as in the “Dark Ages”.

Scott Pruitt’s second point about climate warming being a bad thing is at best American-centric and naive. If one is living in Iowa, for example, one might agree that a degree or two (or three) of warming wouldn’t be such a big deal. However, temperature rise doesn’t come in isolation. With it comes melting of ice and rising sea levels, and increased intensity of storms, and changing rainfall distributions. For example, the sorts of sea level rises that are predicted if warming continues in a “business-as-usual” scenario means much of the East coast of the USA’s major cities will be, if not totally underwater, then subject to increasing frequencies of flooding events that will most likely be more extreme and costly than Houston or New Orleans. And this is just to take an American perspective; within the last few years we have seen such extreme heatwaves in India, for example, that thousands of people have died. Just one or two degrees change as a global average can make the difference between these being very warm days and these being deadly heatwaves.

In response to Scott Pruitt’s last point about an “ideal temperature,” I would suggest he asks the residents of Kiribati and Vanuatu (or even the Netherlands or Bangladesh), whose houses are at risk from sea level rise, what surface temperature they would like to see in 2100.