Flawed reasoning: Climate change is an observable phenomenon – not just a ‘theory’ – and is supported by robust scientific evidence. It is flawed reasoning to suggest that climate scientists’ need to be able to accurately predict the exact number of hurricanes in a season to validate the concept of climate change. Seasonal hurricane predictions and climate change are separate concepts with different time scales and methods of study.

REVIEW

CLAIM:

MW*: “There was a lot of talk about this being an incoming historic hurricane season. You know, because of climate change and all that jazz. But then a funny thing happened during the historic hurricane season, and that is nothing. Nothing happened. There were basically, like — there were no hurricanes.”

MW*: 'Climate change theory is flawed because it cannot exactly predict how many hurricanes there will be. A theory should be able to make predictions, so if a theory makes a prediction that does not come to pass, there is something wrong with the theory.'

BS*: The uncertainty in the data for global warming's effects on hurricanes is fairly high and climate scientists “don’t actually know all that much”; they cannot predict how many hurricanes there will be or their intensity.'

Note:

*Claims in apostrophes are paraphrased and claims in quotation marks are direct quotes.

In early September 2024, Daily Wire hosts Matt Walsh and Ben Shapiro made several claims about the 2024 hurricane season with Ben Shapiro calling it a “light season” and Matt Walsh claiming there were “no hurricanes”. In separate videos, both Ben Shapiro and Matt Walsh attempted to undermine climate scientists’ knowledge of climate change based on a discrepancy between the forecasted 2024 hurricane season and what has occurred thus far. On the basis that scientific theories should be predictive, Matt Walsh claimed that ‘climate change theory must be flawed’ because it can’t accurately predict hurricanes each season. Granted, Matt Walsh also admitted he’s ‘no scientist’ – so what do scientists think about this? To answer this question, we contacted several scientists with expertise in hurricanes and climate modeling and shared their comments below. But before we get to those, what are hurricanes exactly and why try to predict them?

There have been 4 hurricanes in the 2024 season thus far – lighter than predicted, but the season isn’t over

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), “a hurricane is a type of storm called a tropical cyclone, which forms over tropical or subtropical waters.” NOAA explains that “Hurricanes originate in the Atlantic basin, which includes the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico, the eastern North Pacific Ocean, and, less frequently, the central North Pacific Ocean”. But what makes hurricanes different from other storms? To be considered a hurricane, a storm must reach a maximum sustained wind speed of 74 miles per hour. With increasing speeds, hurricanes receive a rating or ‘category’ on an increasing scale of 1 to 5. NOAA explains that higher category hurricanes (e.g., Category 5) have a higher potential to cause property damages. As explained in a 2022 paper in Nature Communications: “Hurricanes are among the most costly and deadly geophysical extremes on Earth. Hurricane damage is caused by extreme wind speeds and flooding due to storm surge and heavy amounts of rainfall over relatively short periods of times”[1]. Scientists try to limit these impacts by predicting their arrival and giving people lead time to prepare and make better informed decisions. NOAA’s National Hurricane Center predicts and tracks hurricanes, which occur, on average, 12 times per year in the Atlantic basin (Figure 1), with the typical hurricane season starting on June 1st and ending on November 30th – although hurricanes can also happen outside of this date range.

Figure 1 – Location of the Atlantic basin; a hurricane-forming region spanning a large area of the Atlantic Ocean. Adapted from the following source: Google Earth

On 9 September 2024 – which is near the typical peak of the hurricane season, but still 2 months before it ends – Matt Walsh claimed that ‘no hurricanes’ occurred. However, this is factually inaccurate; NOAA explains that there have been four hurricanes this season thus far – Alberto, Beryl, Chris, and Debby, as named by the World Meteorological Organization. To put this in context, we discussed these claims with tropical-cyclone expert Dr. Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor at First Street, who commented:

Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor, First Street:“Another weakness in Mr. Walsh’s statements is that it’s a large exaggeration to say ‘there were no hurricanes’. I’m not sure when he said this, but we have in fact had 4 hurricanes so far and one major hurricane, and we are likely to see Helene become a major hurricane. In fact, by some measures this season has been above average in activity. That’s not to say that the seasonal forecasts have been accurate so far, but it’s hyperbolic to say that nothing has happened. And we still have 5 weeks or more of potential hurricane activity in front of us.”

Regarding hurricane activity this season, Dr. Karthik Balaguru, Scientist at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, explains:

“For instance, even in this year, Hurricane Beryl became the earliest forming Category 5 storm. However, other factors may have led to the lull in the hurricane season since, such as Saharan dust [see link here].”

As we noted, the hurricane season starts 1 June and ends on 30 November, meaning new hurricanes could form before season’s end, potentially invalidating conclusions some have drawn prematurely. This was also pointed out to us by Dr. Kevin Walsh*, Professor of Meteorology at the University of Melbourne, who explained:

Kevin Walsh, Professor of Meteorology, University of Melbourne:“Incorrect meteorological forecasts do happen, but […] the hurricane season isn’t over yet. Let’s wait until it is before coming to any conclusions about the hurricane season forecasts.”

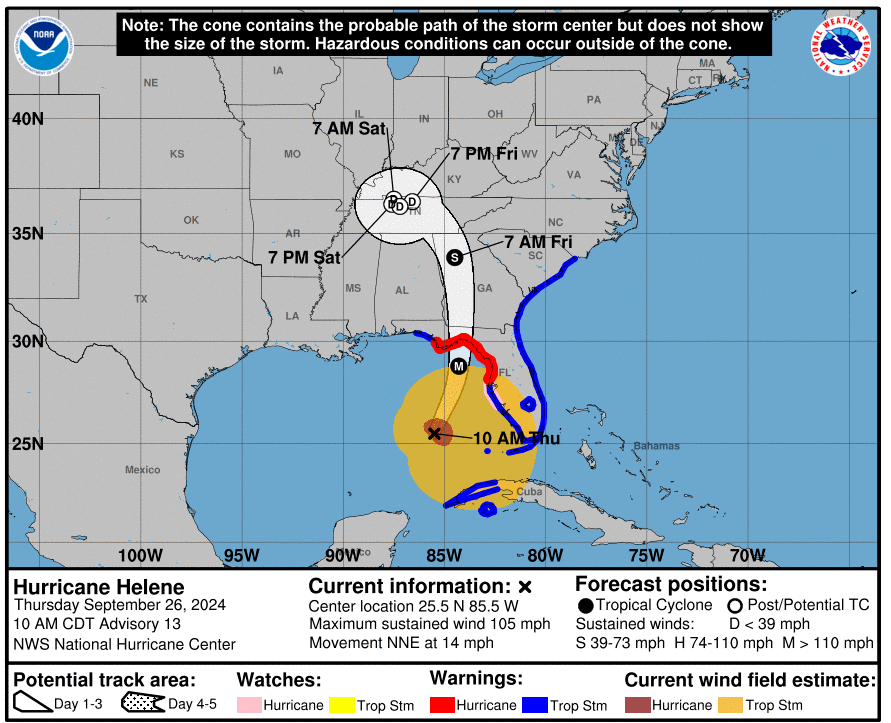

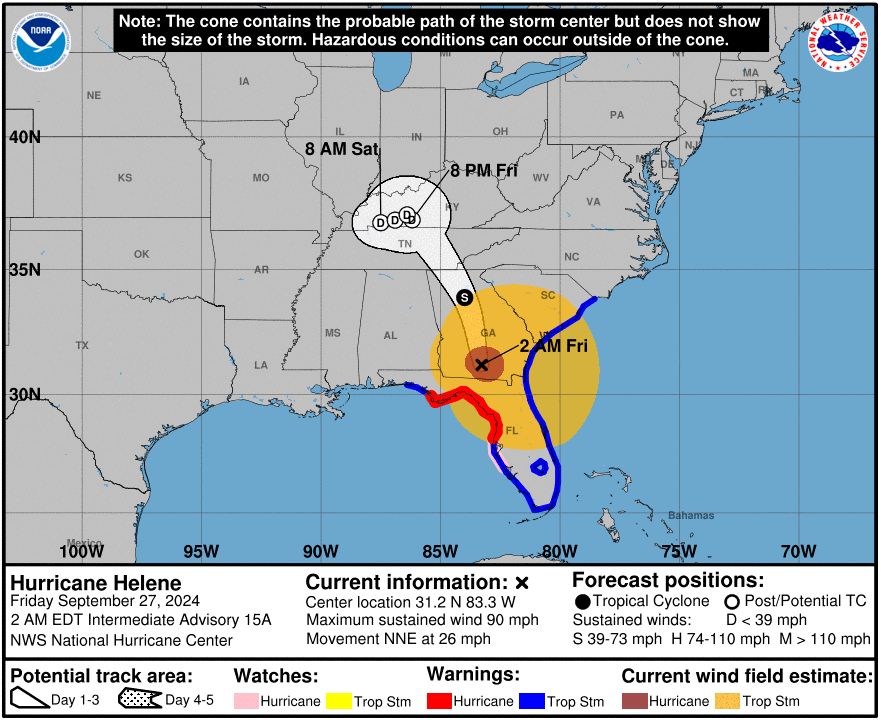

In fact, as we wrote this review, Hurricane Helene was being monitored off the west coast of Florida and a hurricane warning has been issued along the northwest coast of Florida (Figure 2). Before publishing this review, the hurricane moved from the Gulf of Mexico over Florida in the region that was predicted (Figure 3). According to NOAA, at that time, Hurricane Helene was a Category 4 hurricane and had maximum sustained wind speeds of 140 miles per hour; they described the hurricane as “extremely dangerous”. This demonstrates how quickly things can go from ‘quiet’ to dangerous for those in hurricane prone regions. While it is natural to lose faith in predictions that sometimes fall short, there is good reason for staying tuned in to predictions from experts: it could even save your life.

Note: * Dr. Kevin Walsh has no relation to Daily Wire host Matt Walsh.

Figure 2 – NOAA storm/hurricane warnings for Hurricane Helene showing watches and warnings for hurricanes and tropical storms and wind field estimates (26 September 2024 at 10AM CDT). Source: NOAA

Figure 3 – NOAA storm/hurricane warnings for Hurricane Helene showing watches and warnings for hurricanes and tropical storms and wind field estimates (27 September 2024 at 1AM CDT). Note that in a span of only 15 hours Hurricane Helene moved from the Gulf of Mexico, through the northwest coast of Florida, and into southern Georgia (as shown between Figure 2 and Figure 3). Source: NOAA

It is worth noting that late stage hurricanes – while more rare – have also occurred in the past and caused significant damage. For example, Hurricane Sandy which touched down in the United States (U.S.) in late October 2022 was estimated to have caused 65 billion dollars in damage along the east coast.

Hurricane predictions can be ‘hit or miss’, but that does not ‘invalidate’ climate change

Matt Walsh claimed that because theories should be predictive, ‘climate change theory is invalid because it cannot accurately predict the number of hurricanes each season’. However, based on our discussions with climate experts, this is flawed reasoning because it implies that accurate seasonal hurricane predictions are described by climate change theory. But this is not the case and demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of how these concepts and how they differ, as experts explain below. The NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory explains that seasonal hurricane predictions are made using various models which incorporate past hurricane data and known environmental factors such as sea surface temperature, wind patterns, humidity, and El Niño and La Niña events. It is well established that seasonal hurricane predictions are imperfect due to various uncertainties – this is something scientists readily communicate. However, it is misleading to suggest these uncertainties extend to their understanding of climate change – a distinct topic which is studied using different methods and longer time scales. The distinction is well-summarized in a comment we received from Dr. Kerry Emanuel, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

Kerry Emanuel, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, MIT:

“Seasonal prediction of hurricanes is not based on theory but on empirical relationships between the large-scale atmospheric conditions and the frequency of hurricanes. Not one of the many research papers on this topic pretends that these empirical predictions are perfect.”

Note: empirical relationships deal with real-world patterns that we have observed between different variables (e.g., sea surface temperatures and hurricanes). They differ from theories because empirical relationships can approximate ‘how’ things occur without exactly knowing ‘why’.

While there are uncertainties, Ben Shapiro and Matt Walsh make a false leap and claim that these uncertainties indicate a problem with climate scientists’ understanding of the relationship between climate change and hurricanes. For example, on 10 September 2024 Shapiro claimed that “climate scientists want it both ways. They say that when there are hurricanes it is because of global warming, and when there are not hurricanes it is also because of global warming”. And a day prior, Matt Walsh suggested that ‘the concept of climate change is invalidated by climate scientists’ imperfect hurricane predictions’, because “theories must be predictive”. Our discussions with climate experts revealed that these claims are inaccurate and misleading for several reasons. The first is that seasonal hurricane forecasts and climate time-scale forecasts are measured differently. Dr. Kossin elaborates on this in a comment he shared with us:

Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor, First Street:

“The main weakness of Mr. Walsh’s [Matt Walsh’s] statements are that they conflate a seasonal forecast with a climate change forecast. The former is one year or less. The latter is 20-40 years or more. These are fundamentally different in many aspects, just as daily forecasts are fundamentally different from a seasonal forecast. Daily forecasts are only reliable out to 6 days at best and often are a bust even at one day. To say that an inaccurate seasonal forecast means we can’t make a climate time-scale forecast is analogous to saying that an inaccurate daily forecast means that we can’t make a seasonal forecast. Both statements are incorrect.”

Another reason Matt Walsh’s statement is misleading is that it inaccurately portrays climate change as a predictive ‘theory’ that should be able to anticipate all hurricane activity. In reality, it describes observable patterns of change in Earth’s climate. In other words, climate change as a concept does not hinge on the accuracy of hurricane predictions. We discussed Matt Walsh’s claim with Dr. James Elsner, Professor Emeritus at Florida State University, who said:

James Elsner, Professor, Florida State University:

“False. That is like saying all physics is flawed because it cannot exactly predict how the roll of a dice will land. Also, climate change theory explains how the planet warms due to increased amounts of greenhouse gases. The theory is silent on the relationship between greenhouse gases and hurricane activity.”

Dr. Elsner’s comment highlights a subtle difference worth noting: referring to climate change as a ‘theory’ is different from describing ‘changes in the climate’. To those less familiar with the concept, it may sound like climate change – that is, changes in the climate system – is theoretical or unsupported. But this is not the case – there is robust evidence of climate change[2,3]. However, in this case, ‘climate change theory’ is referring to the underlying process that drives climate change – that is, greenhouse gases trapping heat and raising global temperatures (as described in our past review linked here). In a stricter sense, hurricanes are not part of that ‘theory’. However, in a broader sense, changes in the climate system can affect hurricanes – for example, evidence suggests that hurricanes intensity has increased[4]. But what about Shapiro’s claims? While Shapiro is seemingly advocating for more nuance in climate change discussions, some of his conclusions do the opposite by speaking in absolutes. For example, Shapiro claimed that “no one will just come out and say” that there is uncertainty in the data. However, every scientist that we interviewed readily discussed these uncertainties. But these uncertainties do not support Shapiro’s related claim that climate scientists “don’t know all that much” regarding the relationship between global warming and hurricanes. In other words, it’s not ‘black and white’ – there can be both knowns and unknowns. Dr. Kevin Walsh, Professorial Fellow at the University of Melbourne, provided us with the following comment that explains where Shapiro’s statements went astray:

Kevin Walsh, Professor of Meteorology, University of Melbourne:

“I agree with Mr. Shapiro that the uncertainty in the projections of the effects of climate change on hurricanes is pretty high. But this is a lot different from saying that scientists don’t know much. The level of confidence depends on what aspect of tropical cyclones we are talking about. For instance, there is reasonable confidence that the maximum intensity of tropical cyclones is likely to increase. Less certain is whether there are likely to be more or fewer tropical cyclones in a warmer world, but it’s probably fair to say that a global decrease is more likely than an increase. It is very likely that storm surges from tropical cyclones will become more damaging in many coastal regions that are already vulnerable to them, because of highly confident predictions of global sea level rise. Also likely is an increase in maximum rainfall rates, because more moisture is available in a warmer world. Some of these changes may already have been observed. See[extreme storms section in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report linked here]”

Dr. Balaguru shared additional evidence with Science Feedback about how climate change can impact hurricanes:

Karthik Balaguru, Scientist, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory: “there are many studies that have shown that the proportion of intense hurricanes has been increasing[4], storms are producing more rain [5] and storm intensification rates have been on the rise[6]. What climate change does is to make the environment more and more favorable for hurricanes in the longer-term. But whether they form or not in a specific season can also depend on short term or natural variability in the system (eg. El Nino). We should not get confused between the two.”

As climate change drives further global temperature rise[3], tropical cyclones are expected to intensify[7]. As explained to Science Feedback by Dr. Thomas Knutson, Senior Scientist at the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory: “Climate models also project some increase of tropical cyclone intensity, with a magnitude of roughly 5 percent for a 2 degree Celsius global warming scenario[7]”

Conclusion

Scientists study climate change by looking at long-term trends in the climate system (e.g., global temperature increases). Although evidence suggests that climate change has already affected certain aspects of hurricanes (e.g., increasing their intensity), higher uncertainty remains about how hurricane frequency will change. Predictions at shorter time scales (e.g., seasonal forecasts) have inherent uncertainties that can lead to failed predictions. However, failed seasonal predictions do not impact the long-term evidence of climate change. For example, the 2024 hurricane season has seen less activity than predicted; however, in no way does this ‘invalidate’ climate change. Seasonal hurricane forecasts are short-term predictions based on environmental factors (e.g., sea surface temperature, wind patterns, humidity, and El Niño and La Niña events) and past hurricane data. The accuracy of these predictions in a season do not rely on, nor impact the well-established concept of climate change – which is less of a ‘theory’, but rather an observable phenomenon supported by robust scientific evidence.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

Claims:

- 1. Matt Walsh: “There was a lot of talk about this being an incoming historic hurricane season. You know, because of climate change and all that jazz. But then a funny thing happened during the historic hurricane season, and that is nothing. Nothing happened. There were basically, like — there were no hurricanes.”

- 2. Matt Walsh: ‘Climate change theory is flawed because it cannot exactly predict how many hurricanes there will be. A theory should be able to make predictions, so if a theory makes a prediction that does not come to pass, there is something wrong with the theory.’

- 3. Ben Shapiro: ‘The uncertainty in the data for global warming’s effects on hurricanes is fairly high and climate scientists “don’t actually know all that much”; they cannot predict how many hurricanes there will be or their intensity.’

Note:

*Claims in apostrophes are paraphrased and claims in quotation marks are direct quotes.

Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor, First Street:[Response to claims 1-3]

“The main weakness of Mr. Walsh’s [Matt Walsh’s] statements are that they conflate a seasonal forecast with a climate change forecast. The former is one year or less. The latter is 20-40 years or more. These are fundamentally different in many aspects, just as daily forecasts are fundamentally different from a seasonal forecast. Daily forecasts are only reliable out to 6 days at best and often are a bust even at one day. To say that an inaccurate seasonal forecast means we can’t make a climate time-scale forecast is analogous to saying that an inaccurate daily forecast means that we can’t make a seasonal forecast. Both statements are incorrect.

The seasonal hurricane forecasts are generally purely statistical and based on what we have observed in the past. These are not based directly on modeling the complex physics of the atmosphere, and they can perform poorly in any given year for many reasons that have little to do with climate change. Climate time-scale projections need to be considered at long time-scales. This might be compared with the stock market. Day traders will base their forecasts on very different things than people investing in a retirement mutual fund. If a day trader loses their money today, this does not mean that they should liquidate their retirement portfolio.

Another weakness in Mr. Walsh’s [Matt Walsh’s] statements is that it’s a large exaggeration to say “there were no hurricanes”. I’m not sure when he said this, but we have in fact had 4 hurricanes so far and one major hurricane, and we are likely to see Helene become a major hurricane. In fact, by some measures this season has been above average in activity. That’s not to say that the seasonal forecasts have been accurate so far, but it’s hyperbolic to say that nothing has happened. And we still have 5 weeks or more of potential hurricane activity in front of us.

All of this being said, Mr. Walsh [Matt Walsh] and Mr. Shapiro are correct that our long-term projections of hurricane activity have uncertainty in them. More than, say, projections of global average temperature do. We are chipping away at this uncertainty though, and have good confidence that long-term climate change will affect hurricane strength and track. It is true, and it’s no secret, that we have less confidence in predicting how their numbers will change. Judging our ability to forecast hurricane behavior on long time-scales should take everything into account though. Otherwise it’s just cherry picking.”

Kevin Walsh, Professor of Meteorology, University of Melbourne:

1. [Response to claim 1]: “While the hurricane season in the Atlantic is not over yet, it is possible that this will not be a very active hurricane season. This is contrary to the predictions of the seasonal forecasting models, many of which were predicting a very active season. Incorrect meteorological forecasts do happen, but as I said, the hurricane season isn’t over yet. Let’s wait until it is before coming to any conclusions about the hurricane season forecasts.”

2. [Response to claim 2]: “Having said this, the quality or otherwise of seasonal hurricane forecasts for the Atlantic is not that relevant to climate change, as Mr. Walsh [Matt Walsh] appears to be implying. Most scientists would be of the opinion that in the Atlantic, the climate change effect on hurricanes has probably not emerged from the noise yet. One of the reasons is the large year-to-year variability in Atlantic tropical storm and hurricane numbers, as this variability tends to swamp a trend like climate change. See [link here] for a recent authoritative summary. They say “In summary, it is premature to conclude with high confidence that human-caused increases in greenhouse gases have caused a change in past Atlantic basin hurricane activity that is outside the range of natural variability, although greenhouse gases are strongly linked to global warming.” “

3. [Response to claim 3]: “I agree with Mr. Shapiro that the uncertainty in the projections of the effects of climate change on hurricanes is pretty high. But this is a lot different from saying that scientists don’t know much. The level of confidence depends on what aspect of tropical cyclones we are talking about. For instance, there is reasonable confidence that the maximum intensity of tropical cyclones is likely to increase. Less certain is whether there are likely to be more or fewer tropical cyclones in a warmer world, but it’s probably fair to say that a global decrease is more likely than an increase. It is very likely that storm surges from tropical cyclones will become more damaging in many coastal regions that are already vulnerable to them, because of highly confident predictions of global sea level rise. Also likely is an increase in maximum rainfall rates, because more moisture is available in a warmer world. Some of these changes may already have been observed. See https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/chapter/chapter-11/, in the extreme storms section.”

Karthik Balaguru, Scientist, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory:

[Response to claims 1-3]: “Yes, it is true that many predicted an extremely active hurricane season and it has been unusually quiet. But this is seasonal predictability, which is not directly related to climate. Seasonal or sub-seasonal predictability can be challenging at times, as it can be affected by short-term variability in the climate system. For instance, even in this year, Hurricane Beryl became the earliest forming Category 5 storm. However, other factors may have led to the lull in the hurricane season since, such as Saharan dust [see link here]. Climate change on the other hand refers to a long-term (on the order of several decades or longer) change in the system and its [e]ffects on hurricanes are more clear. For instance, there are many studies that have shown that the proportion of intense hurricanes has been increasing[4], storms are producing more rain [5] and storm intensification rates have been on the rise[6]. What climate change does is to make the environment more and more favorable for hurricanes in the longer-term. But whether they form or not in a specific season can also depend on short term or natural variability in the system (e.g. El Nino). We should not get confused between the two.”

James Elsner, Professor, Florida State University:1. [Response to claim 1]: “False. There were at least 4 hurricanes by now, which is about the long-term average. To say “there were no hurricanes” is a lie.”

2. [Response to claim 2]: “False. That is like saying all physics is flawed because it cannot exactly predict how the roll of a dice will land. Also, climate change theory explains how the planet warms due to increased amounts of greenhouse gases. The theory is silent on the relationship between greenhouse gases and hurricane activity.”

3. [Response to claim 3]: “Somewhat true, but misleading. The uncertainty surrounding global warming’s influence on hurricanes is fairly high. We know that hurricanes operate like efficient heat engines (heat-engine theory of hurricane intensity[8] and with all else being equal, warmer ocean temperatures due to climate change (or any other mechanisms for heating the oceans) will result in stronger hurricanes[9,10]. Most of the uncertainty results from the randomness of hurricane frequency. Mechanisms that create hurricanes (as distinct from those that intensify them) are more complicated and those mechanisms are not very sensitive to the amount of additional heat in the ocean (above some threshold).”

Kerry Emanuel, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, MIT:

1. [Response to claim 1]: “There have been 4 hurricanes in the North Atlantic so far this year.”

2. [Response to claim 2]: “Seasonal prediction of hurricanes is not based on theory but on empirical relationships between the large-scale atmospheric conditions and the frequency of hurricanes. Not one of the many research papers on this topic pretends that these empirical predictions are perfect.”

3. [Response to claim 3]: “There is a strong consensus among those [who] study the effects of climate change on hurricanes that these storms will become more intense and produce more rain. Observations of hurricanes strongly support these predictions. On the other hand, research is undecided about how the frequency of hurricanes might change. One quiet season does not invalidate these predictions.”

Thomas Knutson, Senior Scientist, NOAA/GFDL:

1. [Response to claim 1]: “The prediction that this hurricane season would be very active was a seasonal prediction, which is a forecast for the immediately upcoming season. The seasonal Atlantic hurricane prediction problem is based largely on shorter term climate fluctuations like El Nino, and is a different problem from the long-term climate change projection problem for hurricanes. Climate change projections are an attempt to project how various aspects of hurricanes are likely to change in a general sense over the longer term (i.e., the coming century) under warmer climate conditions. Seasonal predictions use various methods including dynamical models to try to forecast the upcoming season. Similarly, future long-term projections of tropical cyclone and hurricane frequency are typically based on model projections, along with examination of historical trends in relevant metrics. A recent assessment of climate change and tropical cyclones concluded that the global frequency of tropical cyclones was projected to decrease due to climate warming, although confidence in this projection was relatively low. Climate models also project some increase of tropical cyclone intensity, with a magnitude of roughly 5 percent for a 2 degree Celsius global warming scenario[7]. This projected intensity change is likely too small a signal to be clearly detectable as a trend in past data, particularly due to limitations of the observational record. Models also project an increase in hurricane rainfall rates in a warmer climate (about 15% for a 2 degree Celsius warming scenario)[7] but again this has not yet been clearly detected in observations, in part due to limitations of and changes in hurricane precipitation observations over time. Sea level rise, all other effects equal, is expected to lead to increased risk of inundation from hurricanes, even if the storm characteristics do not change. For more information, see: https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/global-warming-and-hurricanes/”

2. [Response to claim 2]: “A recent assessment of climate change and tropical cyclones concluded that the global frequency of tropical cyclones was projected to decrease due to climate warming, although confidence in this projection was relatively low. Thus, scientists admit that projecting how hurricane and tropical cyclone frequency will change under climate warming is a difficult task. This does not negate the whole radiative forcing theory of climate change. There are certain aspects of global climate change, like global mean temperature, where scientists have high confidence in certain future projections. For example, confidence is high that global mean warming will continue and that global sea level rise will continue over the next 50 years[3], with the rates of change having some uncertainty due to climate model limitations and uncertainties in future anthropogenic emissions and volcanic activity.”

3. [Response to claim 3]: “It is true that uncertainty in projections the influence of global warming on future hurricane frequency is high. This is a difficult research problem with no easy answers at this stage. There is higher confidence that global warming will cause an increase [in] the rainfall rate from hurricanes, and that the intensity of hurricanes on average is likely to increase. Even those two projections have not yet been detected as trends in past hurricane data, partly due to their size relative to natural variability and to limits of observations. The most confident projection of climate scientists related to hurricanes and their impacts is that in locations with rising sea levels, which is most locations, any hurricanes that do occur will happen on a higher background global sea level than in the past, which is going to generally increase the risk of coastal inundation from the storms that do occur, all else assumed equal. It’s not quite right to say that climate scientists don’t know all that much. For example, we know that U.S. landfalling hurricane frequency has not had any significant long-term increase since 1900 [see Figure 1 (a,b) here][11]. And we know that sea levels have risen in most U.S. coastal regions [see link here; Note the blue dots (decrease in relative sea level) on much of Alaskan coastline, due to large amounts of land rising there as mentioned in the caption]. This is knowing something useful about climate change and hurricanes.”

REFERENCES

- 1 – Reed et al. (2022) Attribution of 2020 hurricane season extreme rainfall to human-induced climate change. Nature Communications.

- 2 – IPCC (2023) Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report.

- 3 – IPCC (2021) Sixth Assessment Report Working Group 1: The Physical Science Basis.

- 4 – Kossin et al. (2020) Global increase in major tropical cyclone exceedance probability over the past four decades. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- 5 – Guzman and Jiang (2021) Global increase in tropical cyclone rain rate. Nature Communications.

- 6 – Balaguru et al. (2024) A Global Increase in Nearshore Tropical Cyclone Intensification. American Geophysical Union: Earth’s Future.

- 7 – Knutson et al. (2020) Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change Assessment: Part II. Projected Response to Anthropogenic Warming. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

- 8 – Emanuel KA (2005) Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature.

- 9 – Elsner et al. (2008) The increasing intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones. Nature.

- 10 – Elsner JB (2020) Continued increases in the intensity of strong tropical cyclones. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

- 11 – Vecchi et al. (2021) Changes in Atlantic major hurricane frequency since the late-19th century. Nature Communications.