In early November, several photos were shared via social media and news outlets showing what was allegedly the ‘first-ever snowfall on record’ in the Al-Jouf (or Al-Jawf) desert in Saudi Arabia. This ignited polarized discussions on social media with some people blaming climate change, and others claiming this ‘contradicts’ global warming.

On an X/Twitter post about the weather event, one user commented “Probably a result of global warming?” Yet, another user wrote ‘Yeah…”global warming” – with SNOW in the DESERT for the FIRST TIME! I don’t know about you turkeys but I’m gonna buy an SUV and start cranking out the CO2 and a blanket!’

Photos showing the visual contrast of ice-white hills in an arid (i.e., dry) desert seemed to stir up confusion about what caused this weather event. So what really occurred and how rare was it? Below we will investigate the details of this weather event and the claims that followed. Stay tuned to read quotes from our discussion with a climate scientist who studies how convective weather hazards – such as hail – respond to anthropogenic climate change.

Main Takeaways:

- The early November 2024 storm in the Al-Jouf (Al-Jawf) region of Saudi Arabia produced hail – not an ‘unprecedented snowfall’, as social media posts and news outlets incorrectly stated;

- A single weather event – such as this recent hailstorm – is not enough evidence to ‘confirm’ or ‘deny’ the occurrence of climate change;

- Climate scientists have determined, however, that climate change is occurring, but came to this conclusion through robust scientific studies at regional and global scales – not by looking at single weather events;

- Hailstorms – while potentially less common in the Al-Jouf region – are not uncommon in Middle Eastern deserts in general;

- Hailstorm severity is expected to increase in most regions; however, climate scientists acknowledge that high uncertainty remains about how climate change will impact hailstorms.

It was hail and rainfall – not snow – that blanketed the desert of Al-Jouf in early November, based on local weather reports.

Despite what recent viral social media posts have stated, it was hail and rainfall – not snow – that coated areas of the Al-Jouf (Al-Jawf) region (Figure 1) in Saudi Arabia on 1 and 2 November 2024, according to the Saudi Press Agency (SPA). However, it is no surprise that many social media posts got this detail wrong, as the same misinformation echoed across multiple online news outlets.

Figure 1 – Location of Al-Jouf (also spelled Al-Jawf or Al-Jowf) in Saudi Arabia. Source: Google Maps

Various sources (linked here and here) shared photos and videos of the Al-Jouf – or ‘Al-Jawf’ – region, claiming that this was the first-ever recorded ‘snowfall’ in this part of the Al-Nafūd desert. However, as the SPA explained, what the storm actually produced was a combination of rainfall and hail – the latter is evident in photos (Figures 2 and 3), which show numerous individual small white spheres – clear characteristics of hail, not snow.

Figure 4 from NOAA NSSL shows different forms of frozen precipitation (i.e., hail, graupel, sleet, and snow). Note the key distinction between hail’s dense semi-spherical shape and snow’s lightly-packed flakes.

Figure 2 – Hail in the Al-Jouf region of Saudi Arabia from early-November 2024. Source: Saudi Press Agency (SPA)

Figure 3 –Hail in the Al-Jouf region of Saudi Arabia from early-November 2024. Source: Saudi Press Agency (SPA)

Figure 4 – Different forms of frozen precipitation. From left to right: hail, graupel (soft hail), sleet, and snow. Source: NOAA NSSL

As explained by the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL):

“Hailstones are formed when raindrops are carried upward by thunderstorm updrafts into extremely cold areas of the atmosphere and freeze […] Hail falls when it becomes heavy enough to overcome the strength of the thunderstorm updraft and is pulled toward the earth by gravity.”

However snow forms in a completely different way. As explained by the National Snow and Ice Data Center:

“Snow forms when the atmospheric temperature is at or below freezing (0°C or 32°F) […] the snow can still reach the ground when the ground temperature is above freezing if the conditions are just right […] As a general rule, though, snow will not form if the ground temperature is at least 5°C (41°F).”

Snow has formed in certain regions of Saudi Arabia in the past – particularly in the mountainous region of Tabuk. In fact, old photos of a snowfall in Tabuk (linked here) have been mislabeled as being part of the recent storm in Al-Jouf (Al-Jawf).

However, reports show that the recent event in Al-Jouf was hail, not snow. This was also checked by the ArabiaWeather Regional Center for Meteorology, who explained:

“In this regard, specialists at the [ArabiaWeather] Regional Center confirmed that the region did not witness any snowfall, and that what happened was heavy hail showers, and that the scenes and images circulated are of hail showers accumulating in the desert and do not show any snowfall.”

The evidence above suggests that recent social media posts and news outlets claiming that ‘Al-Jouf (Al-Jawf) received its first ever snow on record’ are incorrect. While this misinformation alone may seem inconsequential, the public perception that this desert region received its ‘first ever snowfall’ spurred polarized climate discussions rooted in false information.

Furthermore, one of the online news outlets (linked here) posted a video about the event with – what appeared to be – a related interview with Dr. Friederike Otto, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science at Imperial College London, who discussed climate change attribution to weather phenomena. However, after reaching out to Dr. Otto about this video, we received a response from the communications team at Imperial College explaining that “This video of [Dr.] Otto is taken out of context.” So, not only were the details of the weather event incorrectly reported, but the expert opinions were also taken out of context.

In the next section we will explore what climate scientists understand about the connection between climate change and this type of weather phenomenon.

Single weather events cannot ‘confirm’ or ‘deny’ climate change; scientists monitor global climate trends over decades

The misinformation about this weather event spurred many speculative claims. But commenters generally fell into one of two camps: those who claim this ‘proves’ climate change, and those who claim this ‘refutes’ climate change (as seen in the post here). But in fact, both claims are misleading: single weather events cannot ‘prove’ or ‘disprove’ the occurrence of climate change. Single events are only small pieces in a much larger puzzle of Earth’s climate.

In a recent review (linked here), we highlighted some of the key differences between weather and climate – two terms which some people incorrectly use interchangeably. But, in fact, these terms have different meanings and timescales: climate change is typically measured over timescales of decades or more, whereas weather is measured over days to weeks. In this sense, a single weather event is just a small data point in a proverbial ‘sea’ of data that scientists collect and analyze over decades.

This is one reason – as we explained in a past review – why a single weather event (such as a cold week in the middle of summer) does not ‘refute’ the robust evidence of climate change scientists have collected from around the world. Based on extensive research, climate scientists have found unequivocal evidence that global warming is occurring and is primarily driven by increased human greenhouse gas emissions[1]. A single event from one region does not impact these findings – this type of argument is rooted in a misunderstanding of how climate change is assessed.

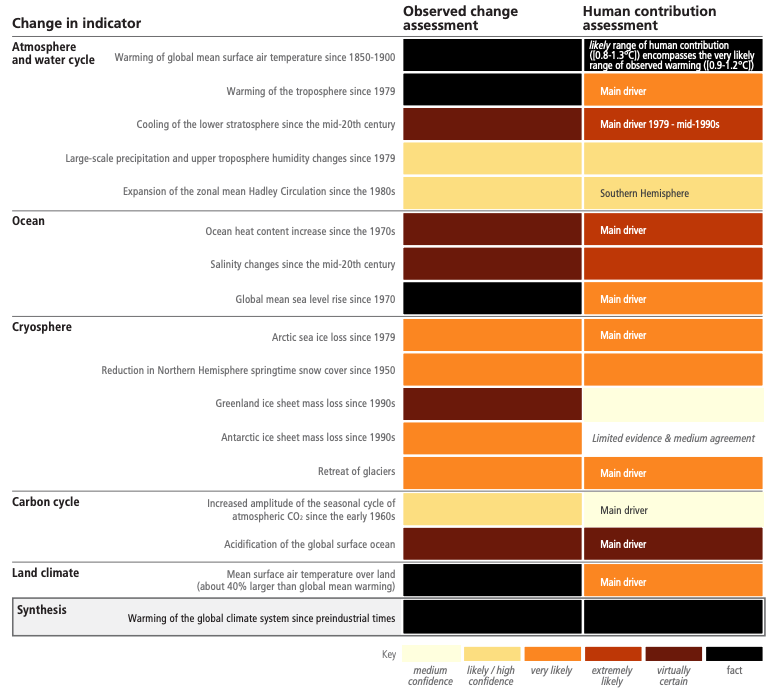

In addition to timescale differences, ‘climate’ also describes more than just atmospheric conditions. More broadly, climate change is assessed by monitoring numerous other climate indicators, which reflect changes in different parts of Earth’s climate system (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Table showing observed changes in climate change indicators for different parts of the climate system. The colors in the first column represent the degree of confidence/certainty in a given change, and the second column represents the confidence/certainty of human contribution to that change. Note that for many of the observed changes in climate indicators, humans have been the main driver with very high likelihood. Source: IPCC (2023)[2]

For these reasons, claims on social media that the early November 2024 hailstorm – often mislabeled as a snow storm – are a result of climate change are misleading. Although there is unequivocal evidence of climate change[1,2], a single weather event is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about climate change. For the same reason, claims that this weather event ‘refutes’ climate change are also misleading.

So how does a single weather event fit into the larger puzzle of Earth’s climate? Climate scientists do know with high certainty that – globally – certain weather events will become frequent and/or severe[1]. However, not all types of weather are equally affected by climate change – nor is every region.

To learn more, we discussed this topic with Dr. Abdullah Kahraman, Senior Researcher in Severe Weather and Climate Change at Newcastle University, whose current research focuses on the responses of weather hazards – such as hail – to anthropogenic climate change.

Dr. Kahraman explained that it can be tricky to attribute a singular weather event, such as this recent hailstorm, to climate change – particularly without dedicating the necessary time and scientific approaches. More specifically, Dr. Kahraman explained:

“Yes, it is really hard to attribute a single extreme event. There are methods to approach that, but it requires a considerably long dedicated time, and connecting it to climate change without proper work could damage the reputation of science, as you are aware.”

But why is that? Dr. Kahraman explained the following:

“Changes in severe convective storms are of high uncertainty. We are more confident on overall increases in moisture with warming, hence convective available potential energy for thunderstorms […] For specific hazards, further analysis is needed, as even [if] an organized storm exists, conditions leading to hail slightly differ from those of tornadoes, for instance. And models tend to have diverse results not only on kinematics, but also on specific layers of the atmosphere. Global models are too coarse to include local effects, and km-scale [kilometer- scale] simulations don’t exist for every region, and even where they do exist, not all possible future scenarios [are] captured due to need for really high computational resources. I think it is fair to say that we don’t know if climate change is increasing these in the middle east or not, at least yet.”

But again, these recent claims about climate change were triggered by what social media users and reporters thought (or at least claimed) was a rare snow event, but – as we’ve demonstrated above – was actually a hailstorm. With added context, is it surprising to see hail in a Middle Eastern desert? Not necessarily.

As Dr. Kahraman explained to Science Feedback:

“Although rare for a given locality, hailstorms are not uncommon in desert areas in the Middle East. Such storms require instability, sufficient moisture, high wind shear, and a small scale mechanism to push the moist air upwards, in order to trigger convection.”

However, broadly speaking, hailstorms are still rare relative to other more common weather phenomena, such as rain. And there lies part of the problem in studying hail in relation to climate change. As explained in a 2021 Nature Nature Reviews Earth & Environment paper, scientists explain that “Efforts to understand the effects of climate change on hail are complicated by the small scale and relative rarity of hailstorms, which make hail hard to observe and model.”[3] The authors also explain that, while modeling suggests that climate change will increase hail severity in most regions, there is still considerable uncertainty[3]. The authors summarized this as follows:

“Owing to a dearth of long-term observations, as well as incomplete process understanding and limited convection-permitting modelling studies, current and future climate change effects on hailstorms remain highly uncertain.”[3]

Conclusion

A recent storm in Al-Jouf (Al-Jawf) blanketed the desert floor with hail, which was mistaken for snow by several news outlets and social media users. This misinformation spread online and sparked discussions about what could cause such a seemingly – although not actually – rare event. Some speculated that this event could either be attributed to climate change or somehow contradicts observed global warming trends; however, both of these statements are misleading. Climate scientists have found unequivocal evidence that climate change is occurring and primarily being driven by human greenhouse gas emission; however, a single weather event is insufficient evidence to ‘confirm’ or ‘deny’ that climate change is occurring. Climate scientists assess climate change by monitoring numerous climate indicators (e.g., global mean surface temperatures) and observing trends in this data over decades or more. Although scientific evidence has shown that climate change has increased the frequency and/or severity of some weather events at a global scale, it is very difficult to link a single weather event to climate change – especially for certain types of events and regions. This is particularly true for changes in severe convective storms – such as those that produce hail – which involves high uncertainty. Climate scientists do not currently know if climate change is affecting hail in the Middle East.

Scientists’ Feedback:

SF: Weather and climate are often mistakenly conflated. However, the IPCC has indicated that climate change can (and has) increased the frequency and/or severity of certain weather events[1]. Given that this recent hailstorm [in Al-Jouf, Saudi Arabia] is a singular weather event in a specific region, is it possible to attribute the event to climate change? Or is that not possible in this case (or for single weather events in general)?

Abdullah Kahraman, Senior Researcher, Newcastle University:

“Yes, it is really hard to attribute a single extreme event. There are methods to approach that, but it requires a considerably long dedicated time, and connecting it to climate change without proper work could damage the reputation of science, as you are aware.

Changes in severe convective storms are of high uncertainty. We are more confident on overall increases in moisture with warming, hence convective available potential energy for thunderstorms. However, stronger convection inhibition limits the effects of it, at least partially. Changes in wind shear are thought to be negative, due to weaker jets in midlatitudes, stemming from uneven warming among the low and high latitudes (poles warm more than tropics), but some studies showed that increases in windshear during the storms could be possible. There are regional differences as well, so it is a really hard to anticipate the future of this component. These apply to all severe thunderstorms. For specific hazards, further analysis is needed, as even [if] an organized storm exists, conditions leading to hail slightly differ from those of tornadoes, for instance. And models tend to have diverse results not only on kinematics, but also on specific layers of the atmosphere. Global models are too coarse to include local effects, and km-scale [kilometer-scale] simulations don’t exist for every region, and even where they do exist, not all possible future scenarios [are] captured due to need for really high computational resources. I think it is fair to say that we don’t know if climate change is increasing these in the middle east or not, at least yet.”

SF: Can you explain what meteorological conditions may have caused this event to occur, given that hail is supposedly rare in that region of Saudi Arabia?

Abdullah Kahraman, Senior Researcher, Newcastle University:

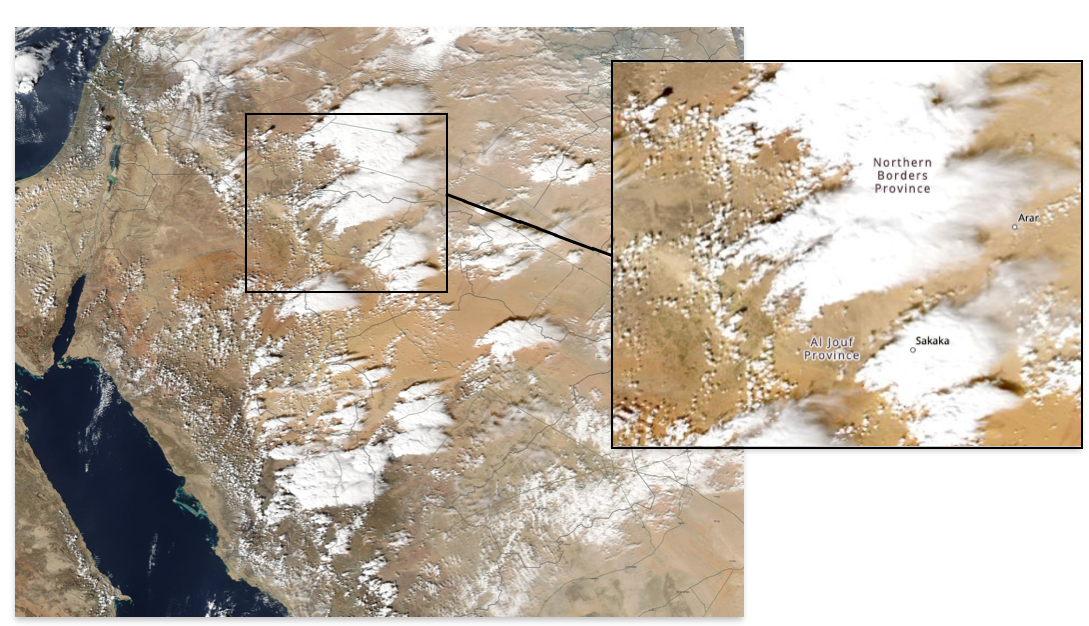

“I have looked [at] what has happened on 2nd of November, and below is the context I can provide. The satellite image [Figure 6] is from NASA’s Aqua, so-called “True Color” product. As this is a polar-orbiting satellite, it captures 2 snapshots per day, and it is likely that the storms visible are in early stages of their lifetimes at the time the satellite passed over the region. EUMETSAT’s geostationary satellites provide better evolution, but I couldn’t reach 15-min interval products, and 3-hour interval images do show the storms moving towards northeast after hitting that region. The spatial resolution is much lower in geostationary satellites, per their distance from the earth.

Although rare for a given locality, hailstorms are not uncommon in desert areas in the Middle East. Such storms require instability, sufficient moisture, high wind shear, and a small scale mechanism to push the moist air upwards, in order to trigger convection. Instability and high moisture usually exists on surrounding seas in the region, occasionally to a higher extent, i.e. thousands of J/kg energy for thunderstorms. What is missing is mostly the high wind shear, and almost always, lift. The lift needed in these regions is very high (sometimes up to a thousand J/kg convection inhibition exists), and convection initiation is not easily achieved due to widespread subtropical high in these latitudes (which is also the reason why the largest deserts lie in these ranges of the planet). One setting that can lead to convection initiation is an extraordinary fluctuation of mid-tropospheric waves, at this time, in the form of an upper level cut-off low over NE Africa. On the eastern flank of this disturbance, southwesterly flow aloft produces positive vorticity advection, which creates upward motion in the region. Furthermore, this not only leads to advection of moist air from the Red Sea and parts of the Mediterranean, but also increases the environmental shear, which helps storm organization. Once the convection is triggered, it becomes well organized, in this case as discrete cells merging with time, sweeping parts of the desert moving along further northeast afterwards. Several storms might have produced hail [on] this particular day, but a thorough analysis is not possible due to scarcity of publicly available weather data for that part of the world.”

Figure 6 – Satellite image of Saudi Arabia captured on 2 November 2024 – the day of the recent hailstorms that formed over Al-Jouf (Al-Jawf) region of Saudi Arabia. [Note: map inlay (right image) and boxes added by Science Feedback for geographic context]. Source: NASA’s Aqua True Color product.

References:

- 1 – IPCC (2021). Sixth Assessment Report.

- 2 – IPCC (2023) Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report.

- 3 – Raupach et al. (2021) The effects of climate change on hailstorms. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment.