Wind energy is the largest source of renewable energy in the United States, and second largest in the world after hydropower.[1] A commonly reported critique of wind energy is that birds sometimes die from collision with its associated infrastructure, such as turbines and transmission lines.[2]

This issue is given a large degree of attention in narratives from groups that are generally opposed to renewable energy or climate policy. However, understanding the impacts of climate change and of our existing fossil-fuel infrastructure on bird populations is necessary to contextualize the damages caused by wind energy and inform an accurate cost-benefit analysis of this renewable resource.

Context is Key

“It is true that renewable energy developments like solar and wind farms (along with the power lines to connect them to the grid) can impact negatively on birds and other wildlife [such as bats], but compared to other human driven causes of bird mortality the impact remains small,” noted Aldina Franco and Jethro Gauld, avian ecologists at the University of East Anglia, in an email to Climate Feedback.

A recent study found that about half of 23 priority bird species are sensitive to renewable energy infrastructure, both wind and solar, in California.[3] The authors found that passerines, small birds like swallows, and raptors, typically larger birds of prey like eagles and kites, tend to be vulnerable to wind infrastructure and are at risk of suffering population-level impacts, or impacts that are large enough to affect the whole population.

The California study was covered by bloggers in Watts Up With That and The Daily Sceptic, two websites that have previously published misinformation about climate science, with Toby Young of the Daily Sceptic equating renewable energy to “avian ecocide.”

Particular attention has been given to raptors. 100% Fed Up, a blog that has published false information in the past, covered the impacts of wind energy on eagles, linking to a video that shows one of these birds suffering a severed wing. The video was retweeted by former Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake, who asked, “Why aren’t environmentalists up-in-arms over this?”

By the proportion of their population, raptors are indeed overrepresented in wind-related fatalities.[4,5] The red-tailed hawk and American kestrel, both of which are listed as “Least Concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, make up most of these deaths in the United States.[4]

However, calculations based on a review of different energy sources and their impacts on birds revealed that wind farms are responsible for about 0.27 deaths per gigawatt hour (a unit of energy; GWh) in the United States, whereas the infrastructure associated with nuclear energy accounts for 0.6 deaths per GWh.[6] Bird deaths caused by nuclear energy are due to both poisoning associated with abandoned uranium mines and collisions with nuclear power plants. Both of these fatality rates are dwarfed by the 9.4 deaths per GWh associated with fossil-fuel energy sources (coal, oil and natural gas), which are caused by a diversity of impacts including mining, collisions, acid rain, pollution and climate change.[6]

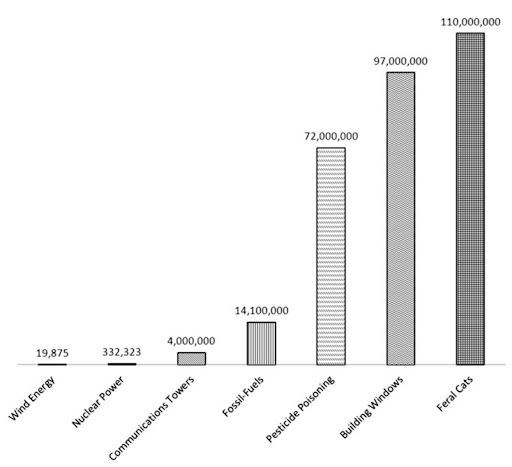

That same study also investigated other anthropogenic impacts on birds. The author found that, in the United States, domestic and feral cat attacks killed 110 million birds, building windows killed 97 million birds and pesticide poisoning killed 72 million birds in 2009 (Fig. 1). By contrast, wind energy was responsible for 19,875 bird deaths during the year. Similarly dramatic contrasts were identified in a 2016 study that looked at bird fatalities in both the United States and Canada. The author found that wind energy killed between 140,000 and 328,000 birds per year, whereas collisions with motor vehicles caused over 200 million bird deaths per year and collisions with buildings caused between 16 and 42 million bird deaths per year.[7]

Figure 1. Bird deaths due to various anthropogenic causes in the United States, 2009. Note that fossil-fuel energy killed more birds than wind energy. Note also that other anthropogenic impacts, such as cat attacks, caused several orders of magnitude more bird deaths than wind energy. Source: Sovacool, 2012.[6]

Climate Change Impacts

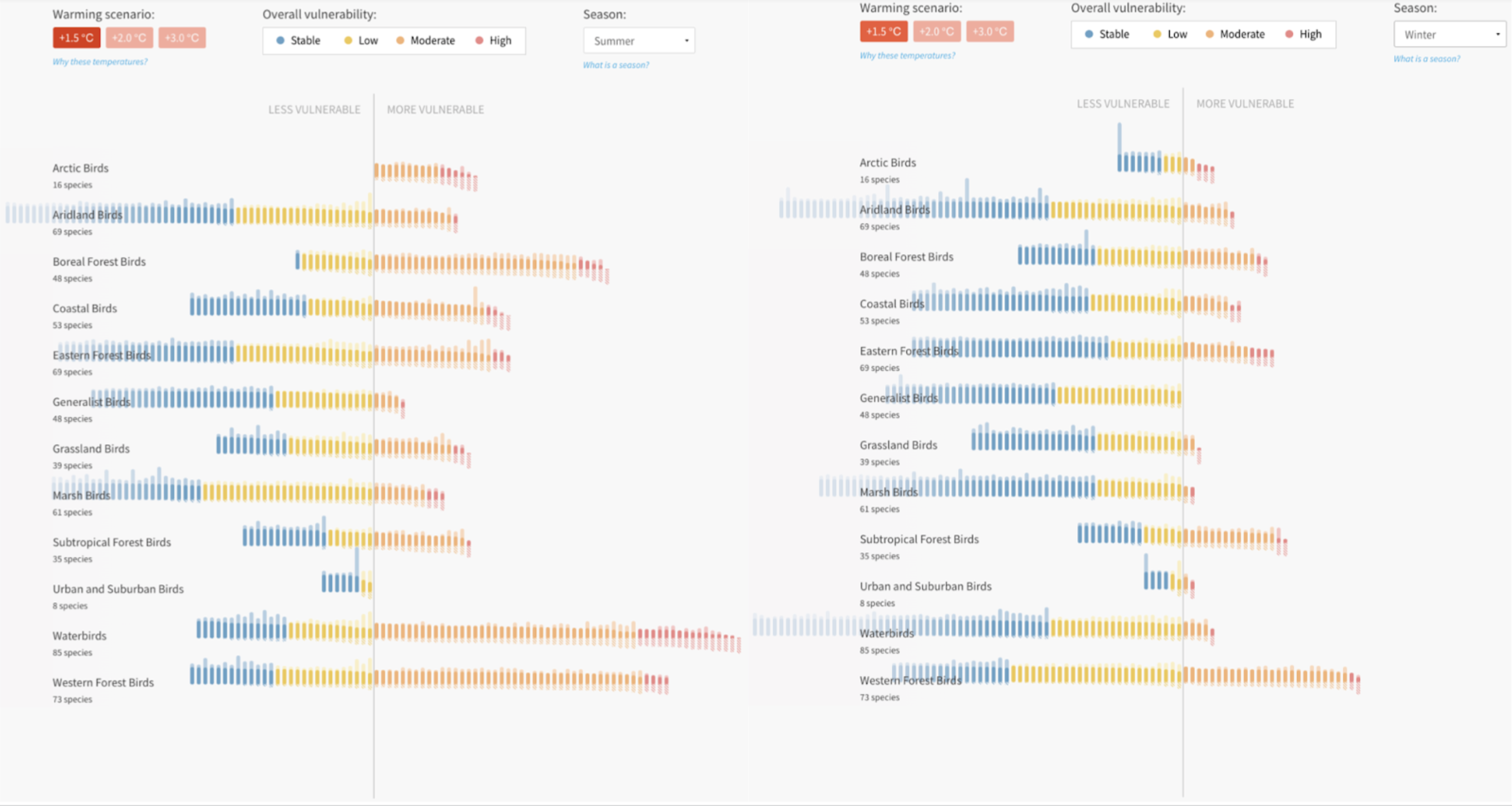

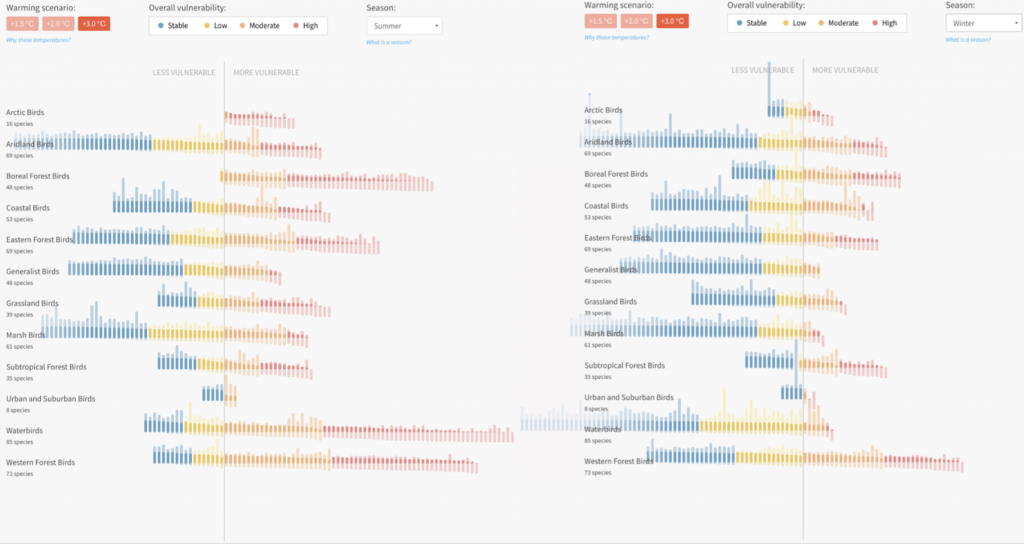

Climate change represents a significant human-caused threat to various bird species. That is because as the planet warms, the geographic area in which birds reside–known as their range–will change. Scientists at the National Audubon Society harnessed 140 million observations to define the range of 604 North American birds. Using climate models, they then estimated changes to the range of these birds under different warming scenarios. The results indicate that climate change drives a redistribution of range, generally resulting in birds relocating to less favorable regions. By limiting warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial temperature, the ambitious target adopted by government signatories to the Paris Agreement, the study found that 76% of vulnerable birds would be better off (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Vulnerability of various North American birds to extinction under the scenario of 1.5 °C warming above pre-industrial temperature during summer (left) and winter (right) seasons. Note that more data to the right of the line, colored by orange and red, indicate higher vulnerability. Compared to 3 °C of warming above pre-industrial temperature, less species are vulnerable to extinction (see Figure 3). Source: National Audubon Society.

Figure 3. Vulnerability of various North American birds to extinction under the scenario of 3 °C warming above pre-industrial temperature during summer (left) and winter (right) seasons. Note that more data to the right of the line, colored by orange and red, indicate higher vulnerability. Compared to 1.5 °C of warming above pre-industrial temperature, more species are vulnerable to extinction (see Figure 2). Source: National Audubon Society.

It isn’t just range that’s changing. As the climate warms, the spring green-up period also shifts, which may affect the timing of bird migration and reproduction. Using both satellite observations and citizen climate data, scientists identified that 9 of 48 passerines throughout North America failed to keep pace with the shifting spring season, potentially leading to deleterious consequences for these species.[8]

Climate change may also affect the availability of food for some birds. A 2019 study, for example, analyzed regurgitated pellets collected from European shags on the Isle of May, Scotland over three decades to understand if the diet of these birds had changed. The authors found that the birds’ consumption of sand eels, previously an important food source, decreased from 1985 to 2014, which they argue could be due to climate-driven declines in the population of sand eels in the North Sea.[9]

Extreme weather events can lead to additional impacts on birds. For example, scientists have found that ground-nesting and neotropical migrant species in western United States are particularly vulnerable to heatwaves and droughts, both of which are expected to worsen under climate change.[10] Some tropical species are also susceptible to intensified heatwaves as well as cyclones, cold spells, and rainfall variability affected by climate change.[11]

“The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, who synthesize the latest research on climate science and the impacts of climate change, estimate that we’re currently on track for approximately 2.5 – 3 °C of warming by the end of this century,” noted Franco and Gauld. “If fossil fuel emission reductions are not implemented fast enough there could be devastating consequences for humanity and wildlife.”

Importantly, the extent of climate impacts on birds may vary by both species and region. And some species in certain parts of the world may be more vulnerable to energy development projects than climate change in the near future. For example, birds in central Europe threatened by wind power “are not the bird species that will suffer most from climate change in the years to come,” commented Wolfgang Fiedler, a bird researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, in an email to Climate Feedback. “In contrast to northerly distributed or mountainous species that already now show clear negative effects of climate change, the species with highest collision risks at power plants [such as some kites, storks and eagles] are different and it is not likely that they will suffer strong population declines due to climate change during the next decades,” Fiedler continued. However, this degree of resilience is not apparent in most of the North American species that have been studied, which generally show high vulnerability to climate change (Figs. 2 and 3).

As such, if one cares about conserving birds, one should also care about addressing climate change. It is nevertheless important to be aware of energy-related risks so that renewable technologies can be deployed in a wildlife-friendly manner. “The impacts of renewable energy infrastructure can be minimized and mitigated, whereas the direct and indirect impacts of fossil fuels are much harder to address,” said Franco and Gauld.

Reducing Risks from Wind Energy

Attention to bird conservation can be made in both the siting and operations of wind farms. When planning to develop a new wind farm, a report by the Renewable Energy Wildlife Institute notes that considerable effort is made to estimate collision risk prior to its construction and operation.[4] High-risk areas, such as those that are known to attract a large number of raptors, ought to be avoided. As such, a better understanding of bird movement will be essential for designing energy infrastructure that is beneficial to both wildlife and humans.

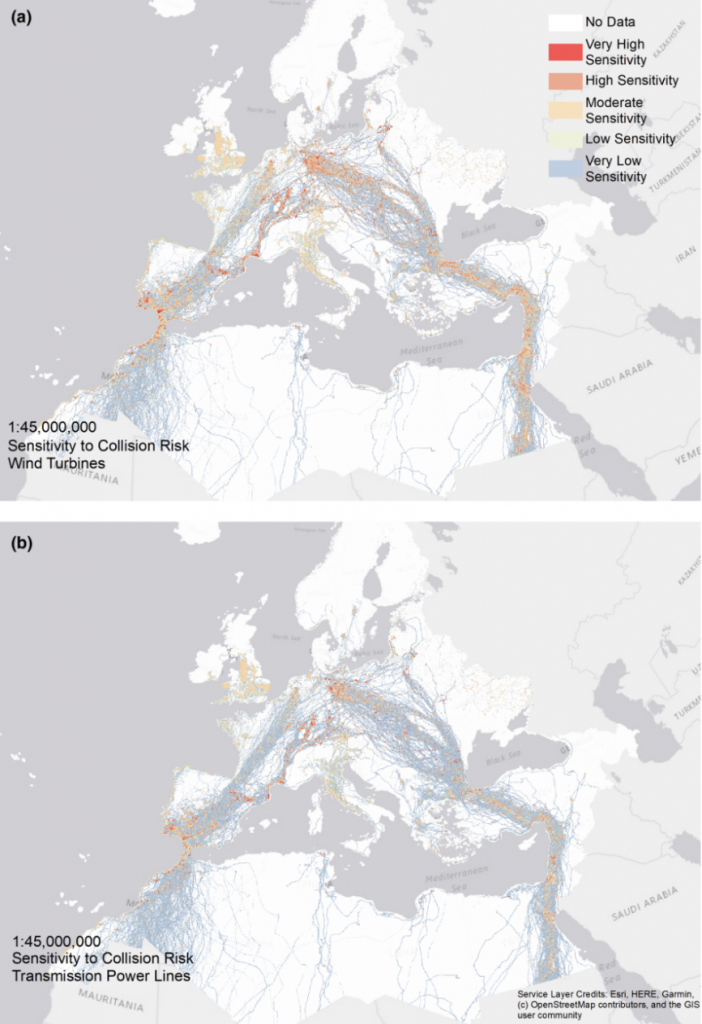

Scientists are working on this very issue. For example, a recent study used GPS data to track the exposure risk of 27 bird species believed to be vulnerable to collisions with energy infrastructure throughout Europe and North Africa.[12] The authors were able to identify “vulnerability hotspots,” where there exist particularly large vulnerability risks (Fig. 4), and recommend that mitigation measures be undertaken at existing energy facilities in such hotspots. At the global level, another recent study found that the expansion of renewable technologies could have a minimal impact on most of the world’s important conservation areas given the appropriate policy and regulatory framework.[13] Such a “nature-positive” approach has already been adopted by some, according to Franco and Gauld, pointing to the Fryslan Wind Farm in the Netherlands.

Figure 4. Sensitivity of 27 species of birds to the risk of collision with wind turbines (upper panel) and with transmission lines (lower panel). Source: Gauld et al., 2022.[12]

Modifications to wind energy operations may also reduce bird fatalities. For example, automated monitoring systems can be installed at wind facilities to track nearby vulnerable species. When these species are within a certain range of a wind farm, these systems slow or stop turbine activity. One study found that such measures decreased the number of golden eagle fatalities by 63% in a Wisconsin wind facility.[14] Scientists are also investigating the possibility of increasing the visibility of rotor blades as a means of reducing collisions[15,16], although this has been met with mixed results.[4]

In summary, the impacts of wind energy on birds need to be contextualized by comparing them to the impacts of fossil-fuel infrastructure and climate change if one wants to design policies that preserve birds. Activists opposed to wind energy routinely highlight the impact turbines can have on birds, but rarely mention the impacts of other forms of energy, thus misleading their audience into believing that wind energy is a bigger problem for birds. As Franco and Gauld noted, ignoring this context “fits within a wider strategy of delay tactics to hinder climate action,” which is required for the conservation of birds and other wildlife.

SCIENTISTS’ COMMENTS

Aldina Franco, Associate Professor, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia:

With input from Jethro Gauld, PhD Student, University of East Anglia

It is true that renewable energy developments like solar and wind farms (along with the power lines to connect them to the grid) can impact negatively on birds and other wildlife but compared to other human driven causes of bird mortality the impact remains small.

It is important to contextualize this in respect to other causes of bird mortality. In raw numbers, Loss, 2016[7] provided a central estimate that combined mortality from wind turbines in the US and Canada is in the region of 140,000 – 328,000 birds per year compared with 16 – 42 million due to collision with buildings and over 200 million killed by collisions with cars and other motor vehicles.

The impacts of climate change (resulting from overuse of fossil fuels) are already affecting many species[17,18] and have the potential to drive species to extinction.[18,19] In terms of comparing the impact of different energy sources on birds, a 2013 study highlighted that fossil fuels cause more bird deaths per unit of electricity produced than wind or solar energy.[6]

When renewable energy developments are situated in inappropriate locations, collision with power lines and wind farms disproportionately affects long lived, large bodied birds like eagles with slow reproduction strategies.[3] Our recent paper highlighted how our current understanding of the movements of birds can help future renewables developments avoid the most sensitive areas such as migratory corridors.[12] Our paper analyzed the impact of power lines used for renewable and non-renewable energy transmission and wind turbines. It is vital going forward that we disincentivize development of energy infrastructure in areas where it would significantly increase collision risks. Onshore energy infrastructure can cause displacement of birds and migratory raptors avoid areas within 1000 m of active turbines. In practice this represents habitat loss[20] but is limited to small areas compared to other human activities (e.g., agriculture).

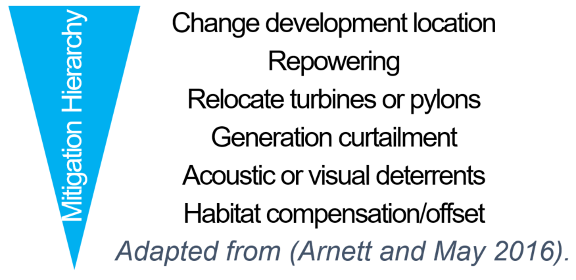

We now have a growing understanding on how to reduce risks to birds from wind energy and how to minimize impacts. These largely fall somewhere on the mitigation hierarchy developed by Arnett and May, 2016[24]:

For example, marking turbine blades or power lines to help make them stand out against the background has been shown by several studies to significantly reduce collisions.[8,9] There are also automated systems which use radar or cameras, sometimes in conjunction with human observers, to shutdown wind turbines as birds move through the area. These shutdown systems are being developed by a number of companies for example in Iberia for onshore systems and in Norway focussing on offshore systems. The message from representatives of wind energy companies at the 2022 Wind Energy and Wildlife Conference was that they are keen to implement these kind of measures to reduce the risk to wildlife but they need to be able to plan and budget for this at an early stage in the development process. Thus, it is vital that all developments are subject to appropriate environmental impact assessments. The Dutch government has shown how with proper planning, mitigation and community involvement, it is possible to build a “nature positive” wind farm, the Fryslan Wind Farm which was constructed in Ijsselmeer, Netherlands. At a global scale, a recent analysis highlighted how with appropriate policy guidance, the expansion of renewables is compatible with efforts to expand protected areas.[13]

On climate and the impact of fossil fuels, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), who synthesize the latest research on climate science and the impacts of climate change, estimate that we’re currently on track for approximately 2.5 – 3°C of warming by the end of this century. If fossil fuel emission reductions are not implemented fast enough there could be devastating consequences for humanity and wildlife. While it is important that detailed environmental impact assessments are undertaken for wind and solar developments alongside mitigation actions to reduce risks to birds, it is vital to the future of humanity and birds that we rapidly phase out fossil fuels from the energy mix. The impacts of climate change are already visible with bird species changing their distributions and life cycles.[22]

In summary, the impacts of renewable energy infrastructure can be minimized and mitigated, whereas the direct and indirect impacts of fossil fuels are much harder to address. We recognise that some groups/lobbies fail to contextualize the impact of renewables alongside that of other sources of energy generation. This, unfortunately, fits within a wider strategy of delay tactics to hinder climate action[23] by those set to lose out financially in the short term from rapid action to phase out fossil fuels as we (under the Paris Agreement at COP21) strive to limit climate warming to well below 2°C.

Wolfgang Fiedler, Research Scientist, Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior:

In the part of the world where I live (Central Europe) the effect of power plants on the mortality of some bird species (Red Kite might be the most prominent one in our national discussion since this is one of the few bird species where Germany holds a significant proportion of the world population) are short term and visible now whereas the effect of climate change is long term and it is likely that this and the next few generations of birds will suffer only very moderately from it’s effects. The majority of the fossil-fuel infrastructure is far away and almost no one here is aware of the pollution problems caused by the oil industry. I personally think it is not bad if the problematic side effects of gaining usable energy are noticeably close to the place where the energy is used insofar as it is fair if everyone sees what is the back side of his energy consumption. Talking of the populations of birds that are threatened by wind power plants in our region, I have to say that those are not the bird species that will suffer most from climate change in the years to come. In contrast to northerly distributed or mountainous species that already now show clear negative effects of climate change the species with highest collision risks at power plants are different and it is not likely that they will suffer strong population declines due to climate change during the next decades.

Sources: see the population trends in EBCC [European Bird Census Council] Breeding Bird Atlas[24] for highly collision-sensitive species such as Red Kite, White-tailed Eagle, Black Stork, Lesser Spotted Eagle. Their population trends are largely driven by (illegal) hunting and its prevention and by anthropogenic habitat change (not directly linked to climate change)

References

- [1] Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, Renewable energy

- [2] Drewitt and Langston (2006), Assessing the impacts of wind farms on birds. Ibis.

- [3] Conkling et al. (2022). Vulnerability of avian populations to renewable energy production. Royal Society Open Science

- [4] Renewable Energy Wildlife Institute (2021). Wind energy interactions with wildlife and their habitats: a summary of research results and priority questions

- [5] Heuck et al. (2019). Wind turbines in high quality habitat cause disproportionate increases in collision mortality of the white-tailed eagle. Biological Conservation

- [6] Sovacool (2012). The avian and wildlife costs of fossil fuels and nuclear power. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences

- [7] Loss (2016). Avian interactions with energy infrastructure in the context of other anthropogenic threats. The Condor: Ornithological Applications

- [8] Mayor et al. (2017). Increasing phenological asynchrony between spring green-up and arrival of migratory birds. Scientific Reports

- [9] Howells et al. (2018). Pronounced long-term trends in year-round diet composition of the European shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis. Marine Biology

- [10] Albright et al. (2010). Combined effects of heat waves and droughts on avian communities across the conterminous United States. Ecosphere

- [11] Şekercioğlu et al. (2012). The effects of climate change on tropical birds. Biological Conservation

- [12] Gauld et al. (2022). Hotspots in the grid: Avian sensitivity and vulnerability to collision risk from energy infrastructure interactions in Europe and North Africa. Journal of Applied Ecology

- [13] Dunnett et al. (2022). Predicted wind and solar energy expansion has minimal overlap with multiple conservation priorities across global regions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- [14] McClure et al. (2021). Eagle fatalities are reduced by automated curtailment of wind turbines. Journal of Applied Ecology

- [15] Bernardino et al. (2019). Re-assessing the effectiveness of wire-marking to mitigate bird collisions with power lines: A meta-analysis and guidelines for field studies. Journal of Environmental Management

- [16] May et al. (2020). Paint it black: Efficacy of increased wind turbine rotor blade visibility to reduce avian fatalities. Ecology and Evolution

- [17] Buchan et al. (2022). Spatially explicit risk mapping reveals direct anthropogenic impacts on migratory birds. Global Ecology and Biogeography

- [18] IPCC (2021). Assessment Report 6

- [19] Thomas et al. (2004). Extinction risk from climate change. Nature

- [20] Santos et al. (2022). Factors influencing wind turbine avoidance behaviour of a migrating soaring bird. Scientific Reports

- [21] Arnett and May (2016). Mitigating wind energy impacts on wildlife: approaches for multiple taxa. Human-Wildlife Interactions

- [22] Pearce-Higgins and Green (2014). Birds and climate change. Cambridge University Press

- [23] Lamb et al. (2020). Discourses of climate delay. Global Sustainability

- [24] European Bird Census Council (2020). European Breeding Atlas