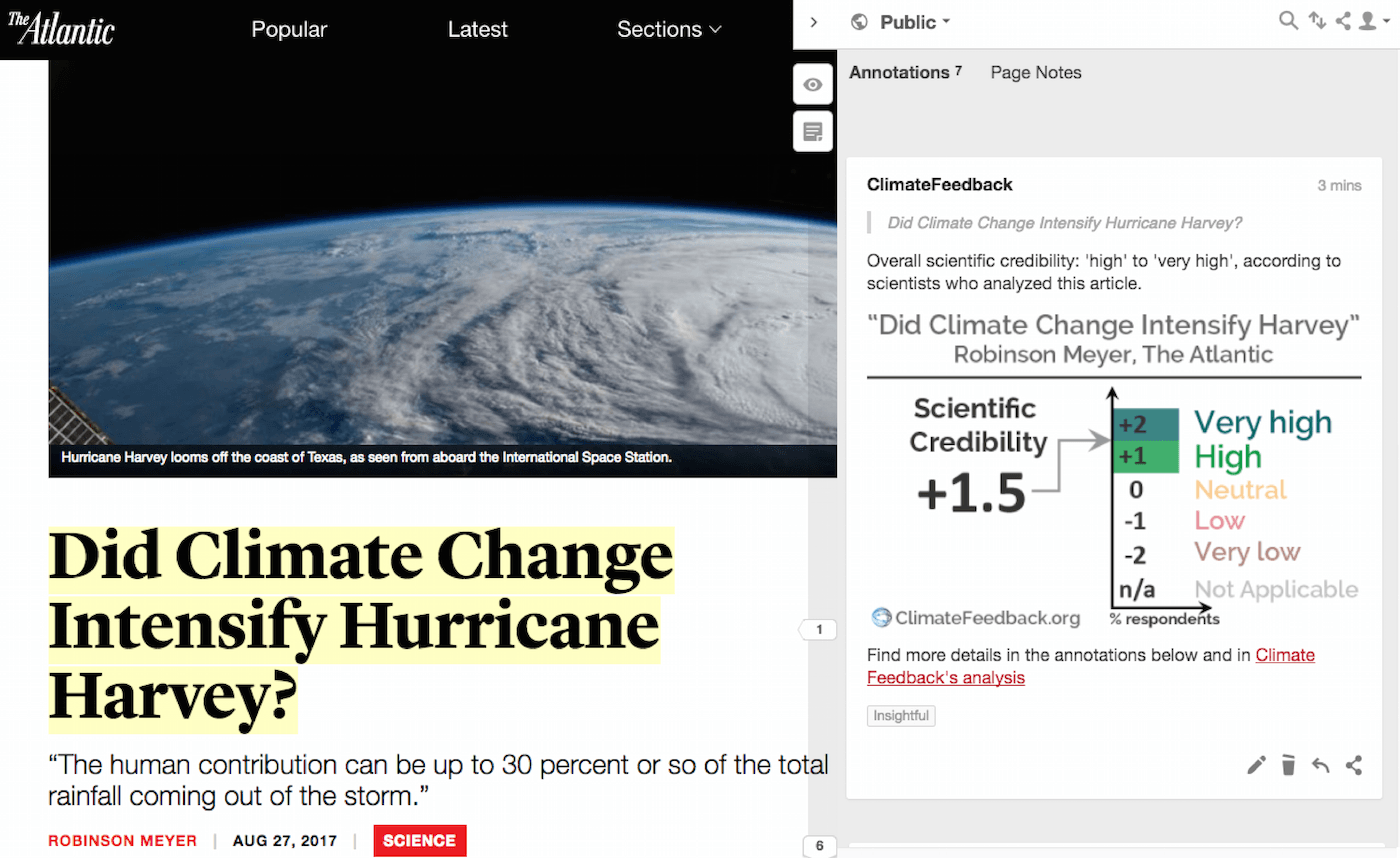

Three scientists analyzed the article and estimated its overall scientific credibility to be ‘high’ to ‘very high’. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Insightful.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This article in The Atlantic attempted to investigate what can be said about the relationship between Tropical Storm Harvey and climate change. Harvey’s record rainfall totals around Houston, Texas are partly the result of how long it has persisted in the same location, making it an unusual storm.

Scientists who reviewed the article indicated that it provides an accurate summary of how tropical cyclones are expected to change due to global warming, as well as what aspects of Harvey do not have clearly understood relationships with climate change.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

This article provides an excellent overview of Hurricane Harvey with good explanations of why it’s so extreme and how climate change may have contributed to this event.

Karthik Balaguru, Scientist, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory:

Overall I think it’s a well written article that captures the essence of our understanding that under climate change storms will likely bring more rainfall. In the case of Harvey, all we can say is that it is consistent with those ideas. But we cannot say that it is the direct consequence of climate change.

Dan Chavas, Assistant Professor, Purdue University:

One must be careful not to assume that warmer waters automatically make all aspects of extreme weather worse. Though for a given storm we do expect rainfall rates to increase at a warmer sea surface temperature, how storm size, regional counts, and track characteristics (e.g. the likelihood that a storm will become nearly stationary as was the case with Harvey) will change in a warmer world are much less well understood.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“But [climate scientists] say that aspects of the case of Hurricane Harvey—and the recent history of tropical cyclones worldwide—suggest global warming is making a bad situation worse.”

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

This is a reasonable statement. As tropical cyclones are such complex events— the confluence of many factors coming together—it is difficult to estimate the climate change role in such events. However, it is likely that human-caused climate change has worsened aspects of this event as described later in the article.

Dan Chavas, Assistant Professor, Purdue University:

It is true that for a Harvey-like event—a storm at this location in East Texas that is nearly stationary—global warming likely increases the total rainfall. But we do not know whether global warming makes it more likely for a Harvey-like events to occur in the first place. Risk combines both of these probabilities. In combination, then, it is difficult to say whether there is a climate change effect on this type of flood risk.

“The human contribution can be up to 30 percent or so of the total rainfall coming out of the storm”

Karthik Balaguru, Scientist, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory:

Climate change doesn’t cause events like this, but probably makes them worse by making storms (which are strong to begin with) more intense and enhancing rainfall in that process. I don’t think anyone can say with confidence that climate change has made tropical cyclones worse. There’s too much natural variability (Pacific Decadal Oscillation, Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, etc.) and the sample size of intense hurricanes is small. It is consistent with what’s predicted for the future, though. However, I’m not exactly sure where the “30 percent” number comes from for the human contribution to rainfall. For every one degree increase in sea surface temperature, the saturation vapor pressure increases by about 7% based on the “Clausius-Clapeyron” equation. There’s also an assumption that hurricanes will likely get stronger because of climate change, so perhaps the stronger winds will also increase evaporation.

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

A reference here would have been useful as it’s unclear exactly where this number comes from. We know that human-caused climate change can increase both the moisture content of the atmosphere, as described by the Clausius-Clapeyron relation, and the energetics of the storm, as there is increased latent heat release. Both of these climate change-influenced drivers have the potential to cause increased precipitation.

Dan Chavas, Assistant Professor, Purdue University:

Again, it is true that in a warmer world we expect the rain rate to increase significantly. (I am not sure about the 30% specifically, but that doesn’t matter.) Thus, given the existence of a Harvey-like storm—a storm at this location in East Texas that is nearly stationary—global warming likely significantly increases the total rainfall.

However, there is a second probability to account for: how likely is it for a Harvey-like event to occur in the first place? This is a much more difficult probability to assess and we do not know how climate change affects it.

Risk combines these two probabilities. As a result, it is difficult to say whether there is a climate change effect on the likelihood of a flood event of this magnitude.

“The tropical storm, feeding off this unusual warmth, was able to progress from a tropical depression to a category-four hurricane in roughly 48 hours.”

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

This storm was quite remarkable in its intensification. It does seem likely that the warmth of the surface and sub-surface waters, primarily linked to variability but also with a small climate change contribution, enhanced the storm.