Factually Inaccurate The consensus of scientific evidence shows that the average temperature over the Antarctic has not been getting colder. Some of the world’s fastest warming is observed in regions of the continent.

REVIEW

CLAIM: We’re seeing record set for antarctic sea ice extent. Climate models predict that antarctic should be losing sea ice, and it’s exactly the opposite of what’s happening. The antarctic ice cap is not melting, the average annual temperature there is 58 degrees below 0°. There’s not melting going on in the first place, it’s actually growing. The sea ice is at record high because it’s getting colder

Science has shown consistently that adding CO2 to the atmosphere is changing the climate in various ways, including raising the surface temperature of the oceans and atmosphere. As a consequence, scientists anticipate that polar sea ice would decline. This has been observed in the Arctic, which shows a 40% reduction in minimum sea-ice extent over the past 44 years[1]. However, the situation in the Antarctic is more complex because the continent is more isolated from the influence of global warming as explained in this article. This complexity has been seized by climate contrarians to try and cast doubt on the scientific understanding of the impacts of climate change.

The claims that the Antarctic sea ice cover is increasing and that the average temperatures in the continent are getting colder are taken from the 2016 film Climate Hustle, produced by CFACT, an organization part of the climate change countermovement according to a climate change polarization study[2]. A short video snippet from this film has been shared on social media. One post on Instagram received 30 000 likes over a single week in April 2023.

Former climatologist Judith Curry, who called into question the fact that humans are the dominant cause of recent climate change in Congressional Testimony, first claims that “Antarctica sea ice extent is increasing to record levels”. Sea ice extent refers to the cumulative area of all ocean surfaces where water is covered with ice. On the other hand, the terms ice cap and ice sheet refer to ice covering terrain such as land or bedrock. In order to understand the trends in sea ice extent, scientists study its area in February and September, respectively the periods in which the ice cover retreats and peaks.

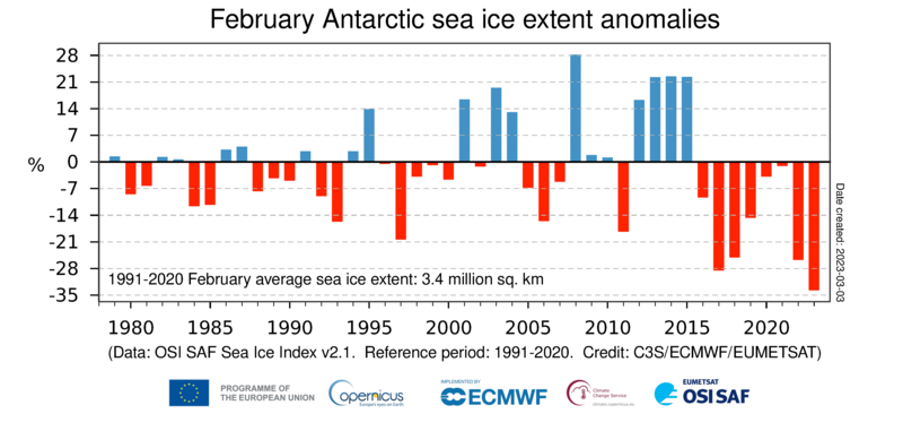

The most accurate data available to detect trends in Antarctic ice coverage are satellite observations, with records starting in the late 1970s. A study compiling 40 years of such records published in 2021 by NASA Research Scientist Claire L. Parkinson found that the Antarctic sea ice cover has been growing very slightly on average until 2014, at which point it started to decrease vigorously at rates “far exceeding the more widely publicized decay rates experienced in the Arctic”[3] (see Figure 1 below). So despite a period of growth between 1979 and 2014, the data shows clearly that the Antarctic sea ice cover is not increasing to “record levels”.

Figure 1 – Time series of monthly mean Antarctic Sea ice extent anomalies for all February months from 1979 to 2023. The anomalies are expressed as a percentage of the February average for the period 1991-2020. Source

In the video snippet, Judith Curry also claims that “climate models predict that the Antarctic should be losing sea ice, and it’s exactly the opposite of what’s happening”. This statement comprises correct and incorrect claims. Overall, climate models did predict a decrease in Antarctic sea-ice cover[4]. For instance, scientists ran the HadCM3 model in 2002 to simulate past sea ice extent between 1970 and 1999. The model simulated Antarctic Sea ice extent decreasing to 12.5 million km2 in 1999 while observations in 1999 showed sea ice extent grew over 14 million km2. Authors of the study attribute the difference with observations to the scarcity of data on the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. By comparison, the model accurately simulated a 2.5% decrease per decade trend in average Arctic sea ice extent for 1970–1999, which is very similar to observations[5].

Nonetheless, current observed trends do not totally contradict these projections, since a shift occurred from a period of sea-ice growth (1979-2014) to a period of sea-ice decline (2014-2022). Moreover, one purpose of models is for scientists to test their understanding of complex issues, and the Antarctic ice coverage is one of those.

“Antarctic sea ice has puzzled modelers for a while. They expected a decrease in sea ice, not a slight increase; and the abrupt change in 2016 was not expected.” comments Eric Rignot, Earth System Science Professor and Chair at UC Irvine, in an email to Science Feedback. Even though the individual elements driving sea ice evolutions are fairly understood, the case for modeling the Antarctic sea ice coverage is especially difficult because of their interactions. “Complex feedbacks involving not only the sea ice and its snow cover but also the ocean, atmosphere and ice sheet (as well as biogeochemical processes)” are the main causes, according to scientist Kyle Clem’s article on Antarctica sea ice predictions[6]. Yet, this subject is not a blind spot in scientific research as, for more than 20 years, numerous scientists have examined reasons for sea ice coverage increase during the 1979-2014 period, formulating different hypotheses[7-10].

In any case, the complexity in modeling Antarctic sea ice extent isn’t enough for undermining all climate models’ accuracy. Indeed, climate models can’t forecast every variable perfectly, but they still skilfully forecasted the evolution of global temperatures. After testing the most prominent climate models predicting global temperature used since 1973, climate scientist and journalist Zeke Hausfather found that “they all show outcomes reasonably close to what has actually occurred”.

Later in the same video, former Geology Professor Don Easterbrook then claims that “the Antarctic ice cap is not melting, [because] the average annual temperature there is 58 degrees below 0°” and then adds “I think it’s getting colder, very simple”.

First, according to measurements reviewed by scientists John Turner and Thomas Bracegirdle in an article for the British Antarctic Survey, there is no evidence to support the claim that it’s getting colder. “Many long-term measurements from Antarctic research stations show no significant warming or cooling trends, and temperatures over most of the continent have been relatively stable over the past few decades” they write[11]. Moreover, temperatures vary greatly depending on the location of the weather station within the Antarctic, which is twice the size of Australia. According to the World Meteorological Association (WMO), in 2022 the average annual temperature ranges from about −10°C (14°F) on the Antarctic coast to −60°C (-76°F) at the highest parts of the interior[12].

Second, surface temperature is not the only factor responsible for ice cap melt. Don Easterbrook shows a lack of understanding of ice caps dynamics with his claim that ‘if the temperature is below 0°C, it cannot melt’. Ice caps are masses of ice formed on the Antarctic’s bedrock, and ice mass changes are dominated by changes in snowfall and glacier flow[13]. Additionally, the ice cap’s grounding lines and the bordering ocean’s temperatures also contribute to mass changes. Contrary to Easterbrook’s claims, observations show that Antarctic’s ice caps can lose mass (i.e. ‘melt’) at current temperatures. In fact, between 2003 and 2013 Antarctica’s ice caps have been losing mass at an estimated rate of 84 gigatons per year, according to a study by University of Bristol researcher Alba Martín-Español[14].

It is also important to note that some regions of the Antarctic are indeed warming. “The Antarctic Peninsula (the northwest tip near to South America) is among the fastest warming regions of the planet, almost 3°C over the last 50 years” said meteorologist Petteri Taalas in an article for the WMO in June 2021[15]. Significant warming is also occurring in the Southern Ocean, bordering the Antarctic. “For what matters most to us, which is sea level rise from melting Antarctica, the air/ocean temperature is increasing in a lot of regions along the coast” confirms Earth Systems Science researcher Eric Rignot. Influencing the Antarctic’s air temperatures, winds, and ice shelves, the Southern Ocean’s warming is yet another evidence of climate change impacting the frozen continent[16].

REVIEWERS’ FEEDBACK

Eric Rignot, Professor, University of California Irvine & Jet Propulsion Laboratory:

The Antarctic sea ice cover has been growing very slightly on average until about 2016*, at which point it started to decrease vigorously. Year to year fluctuations are expected and are not indicative of long term trends. To detect trends, you need multiple years and decades.

The mean ground/air temperature in Antarctica is not getting colder. It also depends on whether you are looking at the coastline or the Antarctic plateau. For what matters most to us, which is sea level rise from melting Antarctica, the air/ocean temperature is increasing in a lot of regions along the coast.

The Antarctic is part of the global climate system and also impacts the global climate system. The evolution of Antarctic sea ice has puzzled modelers for a while. They expected a decrease in sea ice, not a slight increase; and the abrupt change in 2016 was not expected. Overall, a decrease in sea ice cover since the 1970s was expected and observed. There are several interpretations of the recent record of Antarctic sea ice and its switching to a rapid decrease. I will not delve into this because the debate is still open on the thorough interpretation of these observations. I would simply say that it is consistent with a warming signal in Antarctica and the rest of the planet.

*Editor’s note : 2016 is when the average Antarctic sea ice extent for November set a record low. The growth trend previously mentioned started to reverse in 2014.

REFERENCES

- 1 – NASA (2023). Arctic Sea Ice Minimum Extent. Global Climate Change Vital signs of the planet. Date accessed April 15 2023

- 2 – Farrell (2016). Corporate funding and ideological polarization about climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- 3 – Parkinson (2019). A 40-y record reveals gradual Antarctic sea ice increases followed by decreases at rates far exceeding the rates seen in the Arctic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- 4 – Turner et al. (2017). Solve Antarctica’s sea-ice puzzle. Nature.

- 5 – Gregory et al. (2002). Recent and future changes in Arctic sea ice simulated by the HadCM3 AOGCM. Geophysical Research Letters.

- 6 – Clem et al. (2022). Antarctic sea ice# 3: trends and future projections. Antarctic Environments Portal.

- 7 – Thompson et al. (2002). Interpretation of recent Southern Hemisphere climate change. Science.

- 8 – Stammerjohn et al. (2008). Trends in Antarctic annual sea ice retreat and advance and their relation to El Niño–Southern Oscillation and Southern Annular Mode variability. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.

- 9 – Bintanja et al. (2013). Important role for ocean warming and increased ice-shelf melt in Antarctic sea-ice expansion. Nature Geoscience.

- 10 – Swart et al. (2013). The influence of recent Antarctic ice sheet retreat on simulated sea ice area trends. Geophysical Research Letters.

- 11 – John Turner et al. (2022). Antarctica and climate change. British Antarctic Survey. Date accessed April 21 2023.

- 12 – World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (2021). Antarctic heat, rain and ice prompt concern. World Meteorological Organization. Date Accessed April 21 2023.

- 13 – Pörtner et al. (2019). The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate. IPCC special report on the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate.

- 14 – Martín-Español et al. (2014). Spatial and temporal Antarctic Ice Sheet mass trends, glacio-isostatic adjustment, and surface processes from a joint inversion of satellite altimeter, gravity, and GPS data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface.

- 15 – WMOs Evaluation Committee (2021). WMO verifies one temperature record for Antarctic continent and rejects another. World Meteorological Organization. Date Accessed April 21 2023.

- 16 – Holland et al. (2020). The southern ocean and its interaction with the Antarctic ice sheet. Science.