Inaccurate: Retaining an old combustion engine car is less beneficial for the climate than replacing it with an electric vehicle (EV), which offsets the initial emissions in a few years (driving ~40,000 km), particularly when the EV is lightweight and equipped with a smaller battery.

REVIEW

CLAIM: The EU could SEIZE and SCRAP your old car if it doesn't meet their criteria as part of their climate agenda. Repairing an already existing car with spare parts is by far the best thing to do if you care about carbon emissions.

In July 2023, the European Commission introduced a regulation proposal for end-of-life vehicles (ELV) to enhance vehicle life-cycle circularity in the European Union (EU). This initiative aims to ensure that vehicles are used to their fullest potential and that their components are recycled or repurposed at the end of their lifecycle.

Following its announcement, numerous claims emerged on social media suggesting that the regulation would allow the EU to infringe on personal freedoms and threaten car ownership under the alleged guise of climate change and environmental concerns.

The new end of life vehicles regulation targets the automotive industry, not consumers

One such viral post was published by Peter Imanuelsen, also known as “Peter Sweden”, who has regularly shared climate change misinformation according to Climate Action Against Disinformation. Imanuelsen claimed that the EU could “SEIZE and SCRAP your old car if it doesn’t meet their criteria as part of their climate agenda.” His post further claimed that the state would dictate “how long you will be allowed to own your car”, suggesting there would be mandatory scrapping of vehicles that miss their regular EU checkup for two years or if the cost of repairing a car exceeds its market value.

In reality, the EU Commission’s proposal does not mandate the seizure and scrapping of vehicles simply for not meeting certain environmental criteria. Instead, it provides guidelines for assessing vehicles that are neither economically repairable nor roadworthy, without stipulating specific consequences. In accordance with this, Annex 1 of the ELV proposal specifies that a vehicle is considered economically irreparable if its market value is lower than the cost of the necessary repairs required to meet road worthiness standards in the Member State where it is registered. This clause relates to evaluating the economic viability of repairing a vehicle; it does not enforce the seizure and scrapping of vehicles based solely on their condition.

Furthermore, the EU Commission’s proposal does not specifically target car owners or consumers. The focus is on regulatory measures aimed at manufacturers and the automotive industry. In fact, the proposal is designed to promote new industrial practices in manufacturing and disposal, relevant only to the industrial sector. Thus, there is no evidence in the regulation’s terms that private cars could be seized and scrapped, contrary to Imanuelsen’s claim.

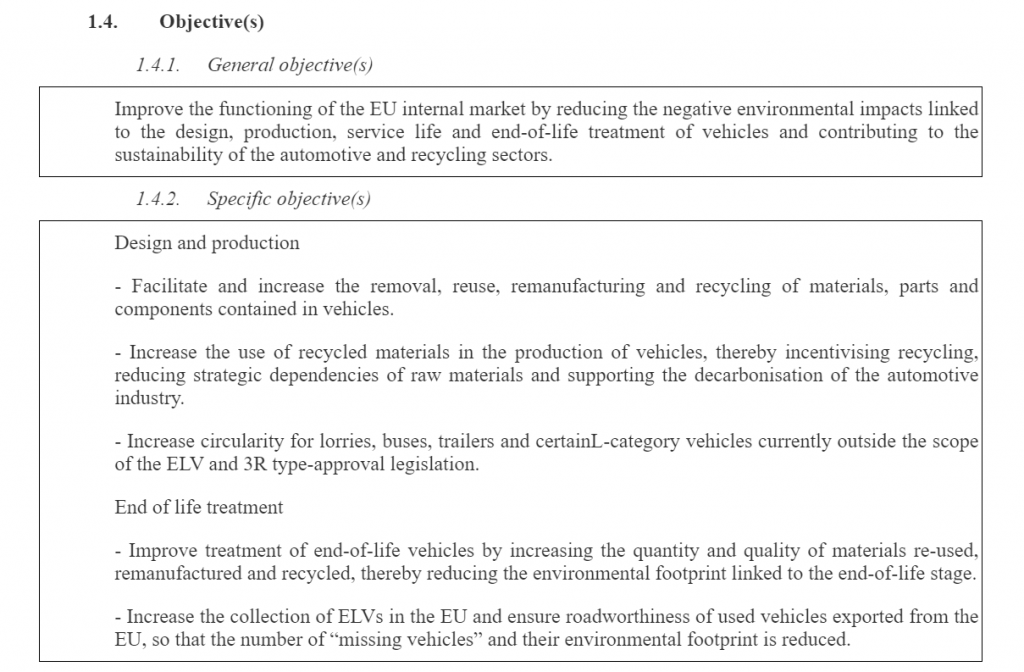

Figure 1 – Extract detailing the proposal’s objectives, in the terms of the EU Commission’s proposal on circularity requirements for vehicle design and on management of end-of-life vehicles (source).

Another document that reacted to the proposal is an online petition against it written by a Swedish bikers’ Magazine, which garnered over 12,000 signatures. The petition claimed that the proposal “concerns the purchase, sale, right to ownership of vehicles, parts and components, repair, renovation, restoration, preservation, and modification.” However, these claims are false, as the proposal does not introduce changes to the private rights related to car modifications. Indeed, the proposal focuses on transforming design and production industry requirements to increase both the quantity and quality of materials that are reused, remanufactured, and recycled (see Figure 1). The regulation’s potential impacts are openly available in an Impact Assessment Report, which is based on feedback from stakeholders.

Would the regulation reduce carbon dioxide emissions?

An overarching claim repeated several times in Imanuelsen’s post is that reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions is merely a pretext for this proposal “to take away your freedom and control your life”. This new regulation is actually very likely to result in reducing carbon dioxide emissions as intended. The increased circularity of car parts and materials will reduce the need for production and shipping of new materials, thereby lowering greenhouse gas emissions associated with manufacturing and transport. This type of circular economy policy is indeed recognized by scientists as an “effective approach to mitigate industrial greenhouse gases emissions” in the latest IPCC assessment’s summary to policy-makers.

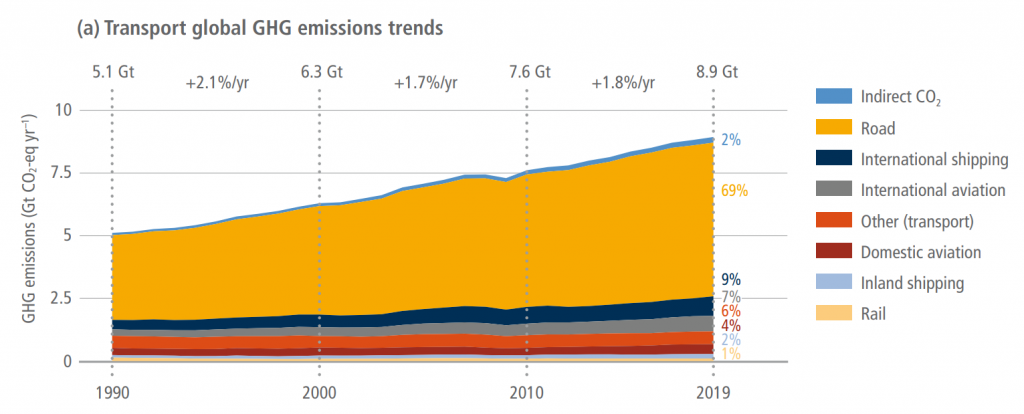

Imanuelsen’s claim overlooks the very significant role of road vehicles in contributing to global greenhouse gas emissions. In 2019, direct greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector accounted for 23% of global energy-related CO2 emissions, according to the IPCC’s latest assessment1. Most importantly, about 70% of direct transport emissions came from road vehicles (see category “Road” in Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Evolution of the transport sector’s global greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions by transportation category from 1990 to 2019. Emissions are measured in gigatons, or billions of tons, of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2-eq). This unit standardizes the climate effects of various greenhouse gases by equating their warming potential to that of carbon dioxide (source).

While most CO2 emissions occur when a car is being driven, reducing emissions in the manufacturing phase still represents a significant opportunity, given the scale of the transport sector’s greenhouse gas emissions. According to the German Environment Agency, the manufacturing phase of an internal combustion vehicle, in case of a lifetime mileage of 168,000 km, has a share of 15% of the overall CO2 emissions (64% for the use-phase, 17% for fuel production and 4% for disposal and maintenance).

The EU Commission has estimated that the proposed regulation would lead to an annual reduction of 12.3 million tons of CO2-equivalent in 2035. To put it into perspective, it can be compared to avoiding about 24 million flights from Paris to Helsinki a year, which emit about 0,5 tons of CO2-equivalent per passenger in Premium Economy class according to myclimate’s flight emissions calculator.

Keeping an older car is not more beneficial for the climate

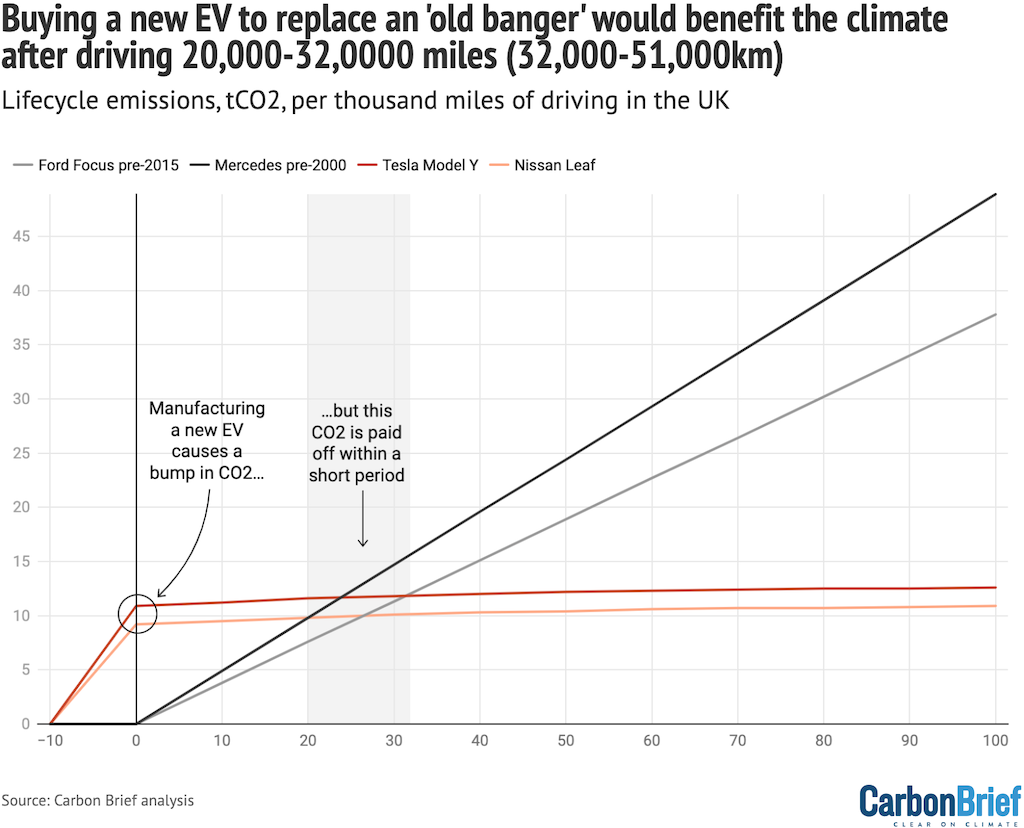

Imanuelsen also claims that “repairing an already existing car with spare parts is by far the best thing to do if you care about carbon emissions”. However, replacing an old, inefficient vehicle with an electric vehicle (EV) does lead to a reduction in carbon dioxide emission. Although there is a bump in CO2 emissions during the production of an EV and its battery, the EV begins to offset these emissions after being driven for approximately 20,000 to 32,000 miles in the UK (equivalent to 32,000 to 51,000 kilometers), as illustrated in the chart below, according to a Carbon Brief analysis.

Figure 3 – Lifecycle tonnes of CO2 (y-axis) per thousand miles of driving in the UK (x-axis) for an old pre-2015 petrol Ford Focus (grey trendline), old pre-2000 petrol Mercedes (black trendline), a new Tesla Model Y (red trendline) or new Nissan Leaf (peach trendline). Purchasing a new EV implies adding new CO2 emissions during its production and during the production of its battery (emissions accrued before the first mile driven, trendlines left of 0 on x-axis), but the lower emissions involved in the operation of an EV mean that these initial emissions are offset within a short period when compared to the continued operation of an old vehicle. After this crossover point (where trend lines cross in the gray shaded area), changing to and operating a new EV results in less total emissions than retaining an “old banger” (source).

This analysis shows that a typical UK driver replacing an old vehicle, colloquially known as “bangers”, with a new electric vehicle (EV) will offset the initial carbon emissions from the EV purchase in about four years. The precise period for this carbon offset is dependent on several factors, including the fuel efficiency of the replaced car, the annual mileage of the driver, and the battery size of the new EV.

Overall, retaining an old combustion engine car is not more beneficial for the climate compared to replacing it with an electric vehicle (EV), particularly when the EV is lightweight and equipped with a smaller battery.

The regulation is expected to undergo several stages before it has a chance of being fully implemented. During this process, the proposal may be amended and will be subject to scrutiny by the European Parliament and the Member States. According to the proposal’s terms, it is acknowledged that implementation could take up to 8 years.

REFERENCES

- 1 – IPCC (2022) Chapter 10: Transport. In: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change