Three scientists analyzed the article and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be 'debated'. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Accurate.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This August 2017 article in The Atlantic covered a study of the greenhouse gas emissions that could be avoided if beef consumption was reduced in the United States. Beef is a particularly resource-intensive food, due in part to the fact that the conversion of plant foods into beef is much less efficient than obtaining calories and protein from plants directly.

Scientists who reviewed the article were divided. While the article summarizes the main points of the paper effectively, some of the context provided is incomplete or potentially misleading. The carbon footprint of dietary choices is a complex topic that can be easily oversimplified, making context critical.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

This is part of a series of reviews of 2017’s most popular climate stories on social media.

GUEST COMMENTS

Gidon Eshel, Research professor, Bard College:

[Prof. Eshel was an author of the study described in this article.]

The story basically relays well the crux of the paper. Simple and to the point, with not much to complain about…

Alejandro Gonzalez, Research Scientist, National Research Council-Argentina (CONICET):

The article is strongly misleading the reader, who at first gets the impression that all beef eaten is from Brazil, which is totally false. Imports account for around 12% of beef consumed in the US, and Brazil contributes with only 5% of imports, while Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Mexico provide 86% of beef imported (see ERS-USDA webpage). Thus, lowering beef consumption in the US is far from affecting Brazilian forests.

On the other hand, it is not true that eliminating beef from diets will produce such reductions in GHG emissions. The author cites conclusions from a single work, but there are hundreds of works published on diet and mitigation of climate change. The consensus is that a well-planned diet change would lower greenhouse gas emissions, but none agree that banning a single product would bring any benefit. Not only beef but all animal products are much less efficient than plant-based ones, and meats other than beef also carry environmental burdens beyond greenhouse gases. The article is very bad—it mixes up sensational keynotes, climate-forest-Trump-beef-Brazil-efficiency-Paris agreement, in a rather random fashion, likely intending to shock the reader and cause excitement.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

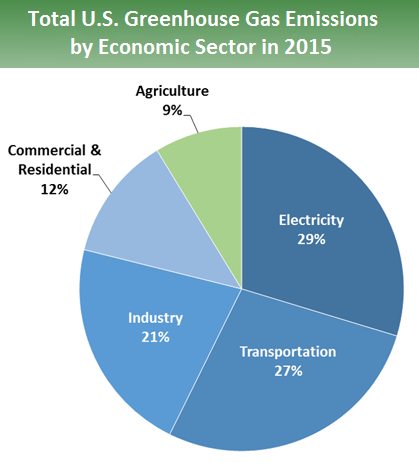

The article reports in a straightforward way on a scientific paper about the potential reductions in greenhouse gas emission in the US resulting from substituting beans for beef. The article explains the issue (meat production diverts crops from humans to cattle) on a simple level. More explanation and more context could have been provided, I think, regarding individual-level and sectoral sources of greenhouse emissions.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Recently Harwatt and a team of scientists from Oregon State University, Bard College, and Loma Linda University calculated just what would happen if every American made one dietary change: substituting beans for beef.”

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

Beans have a carbon footprint between 1-2 kilograms of CO2 equivalent per kilogram, while values for beef range 9-129*. Since they differ in their energy and protein content, the authors of this study calculated separately the CO2 emissions resulting from replacing beans for beef for the same amount of energy or proteins.

- Nijdamet et al (2012) The price of protein: Review of land use and carbon footprints from life cycle assessments of animal food products and their substitutes, Food Policy

“and even if people kept eating chicken and pork and eggs and cheese”

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

A significant share of beef supply in the US comes from dairy cows (around 20% I think)—typically, as processed meat. So switching beef for beans would likely affect the dairy sector as well.

“this one dietary change could achieve somewhere between 46 and 74 percent of the reductions needed to meet the target.”

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

That target should be described explicitly: -17% of greenhouse gas emissions compared to 2005 levels, by 2020. Given that emissions have been decreasing since 2005 (in no uncertain part because of the economic crisis of 2008)—which was already obvious when the Obama Administration made that pledge in 2009—what is needed is a further 7% decrease compared to 2013 levels (according to the authors of the paper cited in this article).

Note, this target is much less than the Paris Agreement: -27% by 2025.

“more so than downsizing one’s car, or being vigilant about turning off light bulbs, and certainly more than quitting showering.”

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

To be honest, the action listed here are rather trivial. I don’t think anybody reasonable is advocating for people to stop showering all together to conserve energy (that’s not even the rationale of the article linked to).

Maybe a more relevant comparison would be against individual carbon emissions from flying, which for people who fly a lot can represent a large part of their footprint.

“Which is to say that these beans will be eaten by cows, and the cows will convert the beans to meat, and the humans will eat the meat. In the process, the cows will emit much greenhouse gas, and they will consume far more calories in beans than they will yield in meat, meaning far more clearcutting of forests to farm cattle feed than would be necessary if the beans above were simply eaten by people.”

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

It would be nice to explain the source of these emissions (methane production, manure management, etc.).

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

Even compared to other meat products, beef has additionally lower meat yield, i.e. the weight of meat produced per kg of live weight*1, and lower energy efficiency (lower energy output per energy input*2).

- 1- Nijdamet et al (2012) The price of protein: Review of land use and carbon footprints from life cycle assessments of animal food products and their substitutes, Food Policy

- 2- Eshel and Martin (2005) Diet, Energy, and Global Warming, Earth Interactions

“Even more, 26 percent of the ice-free terrestrial surface of Earth is used for grazing livestock.”

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

Note that some of this corresponds to marginal lands that wouldn’t necessarily be well suitable for crops, and it could be argued that over such land it would make sense to raise cattle.

“focusing on where efforts will have the highest yield”

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

While there is no doubt that not eating beef would reduce greenhouse gas emissions and may be one the single most efficient individual actions (along with less flying/driving), it’s worth keeping in mind that, according to the EPA, the agricultural sector represents only 9% of US greenhouse gas emissions. (That number is higher world wide—around ~20%—presumably because other source of emissions are also very high in the US…)