On June 1, US President Donald Trump announced his intent to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement. In his remarks, he misrepresented the agreement itself as well as the economic and climatic effects of the greenhouse gas emissions reductions pledged by nations around the world.

To support an argument that participation in the agreement would be economically harmful to the United States, President Trump cited the same National Economic Research Associates report that US Senators Rand Paul and Ted Cruz relied on in recent op-ed articles that researchers have helped us analyze.

The reviewers explain that this report fails to represent our best understanding of the expected impacts of the Paris Agreement. The report only assessed the costs of climate actions, excluding the benefits of avoided climate change and of renewable sources of energy. It also makes a number of important assumptions that lead to extreme estimates of the economic costs.

While the initial emissions reductions pledges submitted as a part of the Paris Agreement are not sufficient to limit global warming to no more than 2 °C above pre-industrial times, they would constitute a significant step towards the actions that would be required to meet that goal. And research shows that the economic effects of the United States’ pledged emissions reductions could be minimal or even positive, as declines in fossil fuel sectors (for example) are compensated by growth in renewable energy sectors and the benefits of improved human health.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

The statements quoted below are from Pres. Donald Trump’s speech; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Compliance with the terms of the Paris accord and the onerous energy restrictions it has placed on the United States could cost America as much as 2.7 million lost jobs by 2025, according to the National Economic Research Associates.

This includes 440,000 fewer manufacturing jobs[…]

According to the same study, by 2040, compliance with the commitments put into place by the previous administration would cut production for the following sectors: paper, down 12 percent; cement, down 23 percent; iron and steel, down 38 percent; coal, and I happen to love the coal miners, down 86 percent; natural gas, down 31 percent.

The cost to the economy at this time would be close to $3 trillion in lost GDP and 6.5 million industrial jobs, while households would have $7,000 less income, and in many cases, much worse than that.” -Pres. Trump

Kenneth Gillingham, Associate Professor, Yale University:

[Comment taken from an evaluation of similar statements.]

It is true that this is what the NERA study says, with many caveats. However, this statement is misleading and taken out of context. There are three reasons for this.

First, and most importantly, the NERA study looked at the costs of a hypothetical set of policy actions. These may not be the actions that will be taken to comply with the Paris Agreement. One could easily model other actions with much lower costs.

Second, it is only the costs that are modeled. The benefits from avoiding climate change (sea level rise, greater storm surges, greater spread of diseases, etc.) are entirely ignored. The net costs from the policies would be entirely different and likely even positive.

Third, there is some cherry-picking going on here. The NERA model is known to be inflexible in how it allows for innovation to influence economic activity, and thus it tends to provide much higher cost estimates than other well-known models such as the U.S. Department of Energy’s NEMS or ICF Consulting’s IPM. The NERA model provides useful information, but it is important for it to be taken in context of model results from other models and not cherry-picked as was done here.

Valentina Bosetti, Professor, Bocconi University:

[Comment taken from an evaluation of similar statements.]

The claim on jobs lost is totally unsubstantiated by any scientific assessment. Depending on HOW we decide to decarbonize, the effect on jobs could be either positive or negative. In general, the large investments in infrastructure required might increase jobs. This is not accounting for the totally unrelated reduction in jobs that will be most likely materialize due to robots*.

- Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper

Gary Yohe, Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies, Wesleyan University:

[Comment taken from an evaluation of similar statements.]

The numbers he quotes are from an analysis that adds new meaning to the term “business as usual”. They look to frame their vision of the future on the basis of static behavior across major sectors of the economy; i.e., they do not allow their sectors to adapt their business operations in response to changes in their economic environment. This allows the analysis to report prices for carbon that vary by orders of magnitude across 4 major sectors and leads them to expecting investment to fall by nearly 20% at a time when increasing investment in alternative energy and new production technologies would allow them to grow their profits and support more jobs. The reported losses in jobs, GDP, and personal income are the result of these rigid assumptions and not their similarly rigid depictions of how the US would implement its plan to meet its Paris Accord target.

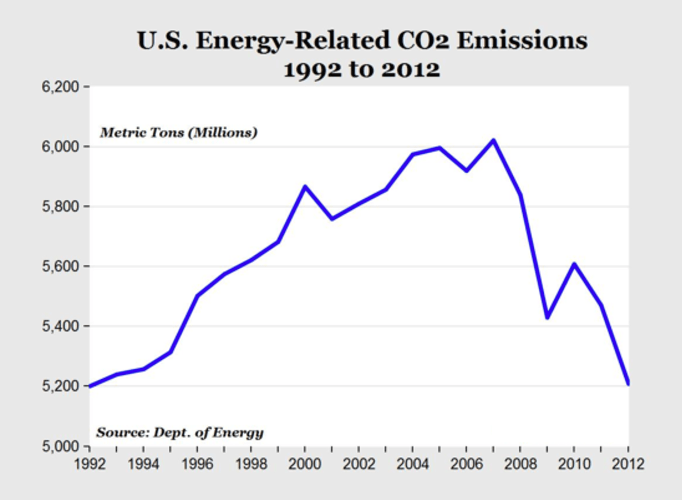

Rather than quote a different report from a different set of experts that show economic growth in both GDP and employment (though they exist, doing so would fall into the same ordering trap as the Senator), let’s look at the recent experience in the United States. The first figure below shows that US carbon emissions have fallen by 14% since 2006, a period of time during which the unemployment rate also fell from nearly 9% to around 4.4% and the annual rate of GDP growth climbed to the historically normal range of 1.5% to 2%.

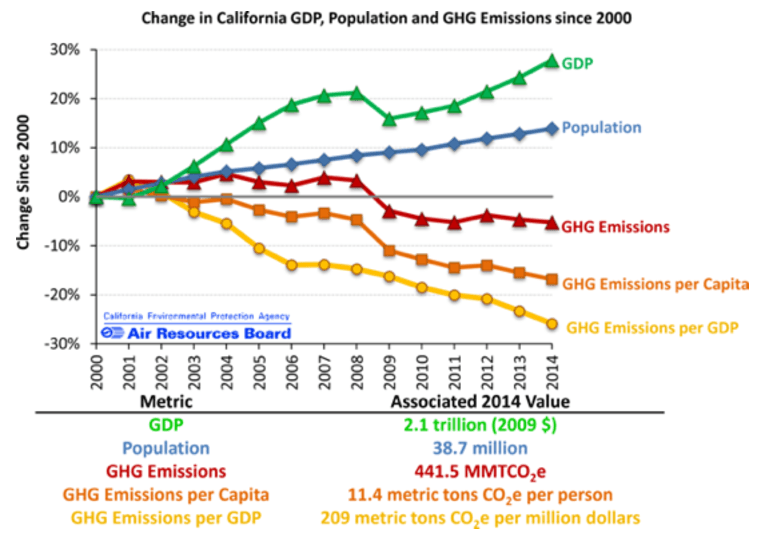

The second figure shows emissions falling in California by nearly 8% since 2008 partly in response to a cap and trade program that has generated $4billion in revenue—revenue that has been used to support investment in adaptation and simultaneous expansion of the employment of less carbon intensive and/or carbon free sources of energy at scale. Over the same period, California GDP has climbed by nearly 10%. These simple economic observations contradict the Senator’s claims.

Energy related carbon emissions for the United States (1992-2012)

Change in California GDP, population, and GHG emissions since 2000. Source: California Air Resources Board, 2015

Bob Ward, Policy and Communications Director, London School of Economics and Political Science:

[Comment taken from an evaluation of similar statements.]

The National Economic Research Associates study assumes that the United States meets the 2025 target for reducing annual emissions of greenhouse gases, which is set out in its “nationally determined contribution”, and goes on to reduce its annual emissions by 80% by 2050 compared with 1990.

The authors of the study admit on pages 10-11 to making the astonishing assumption that every other country in the world ignores the targets in their nationally determined contributions and make no further efforts to reduce emissions, so that much of the calculated costs to the United States economy subsequently arise from high-carbon companies relocate or lose business to competitors in other countries.

The model assumes no increase in low-carbon electricity generation over the next four decades compared with the baseline scenario, so no increase in economic growth or jobs in the low-carbon sector and no substitution of low-carbon energy for high-carbon energy—emissions reductions are achieved by imposing very high carbon prices that reduce the consumption of coal and energy.

The study makes the unrealistic assumption that there will be no economic benefits to the United States from avoided impacts of climate change or co-benefits from reducing local air pollution from fossil fuels which currently contributes to the premature deaths of 200,000 Americans each year, according to a study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology*.

Overall, this is an inaccurate and misleading assessment of the cost to the United States of participating in the Paris Agreement and honouring the commitments in its nationally determined contribution—indeed, the extreme assumptions mean this a study of the costs of policy-makers attempting to achieve emissions reduction targets in some of the least cost-effective ways available.

- Caiazzo et al (2013) Air pollution and early deaths in the United States. Part I: Quantifying the impact of major sectors in 2005, Atmospheric Environment

“Even if the Paris Agreement were implemented in full, with total compliance from all nations it is estimated it would only produce a two tenths of one degree—think of that, this much—Celsius reduction in global temperature by the year 2100.” -Pres. Trump

Gary Yohe, Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies, Wesleyan University:

[Comment taken from an evaluation of similar statements.]

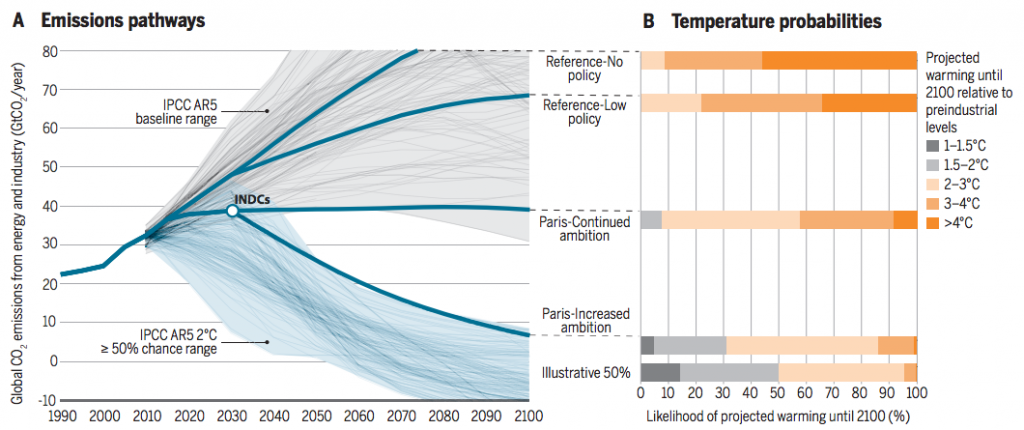

The statement about the climate impact of the Paris Agreement is incorrect. The figure below, appropriated from Fawcett et al (2015)*, displays the nuances of correctly projecting the impact of the Paris Accord through 2100. Business as usual creates an emission trajectory that rapidly passes by 80 gigatons of CO2 per year by 2070; the likelihood of seeing warming less than 3 °C through 2100 along this path is 10% with a median of more than 4 °C. Abiding by the Paris Accord through 2030 and continuing its momentum through 2100 would increase that likelihood to nearly 60% with a median somewhere around 2.5 °C – a reduction of approximately 1.5 °C and not 0.2 °C.

Figure — Ranges of emissions scenarios with and without the Paris Accord through 2030 and beyond. The bars on the right indicate distributions of warming through 2100, and the trajectories show a no policy case as well as a modest policy, the Paris Accord extended, and an accelerated policy case. Source: Fawcett (2015)

- Fawcett et al (2015) Can Paris pledges avert severe climate change?, Science

Valentina Bosetti, Professor, Bocconi University:

[Comment taken from an evaluation of similar statements.]

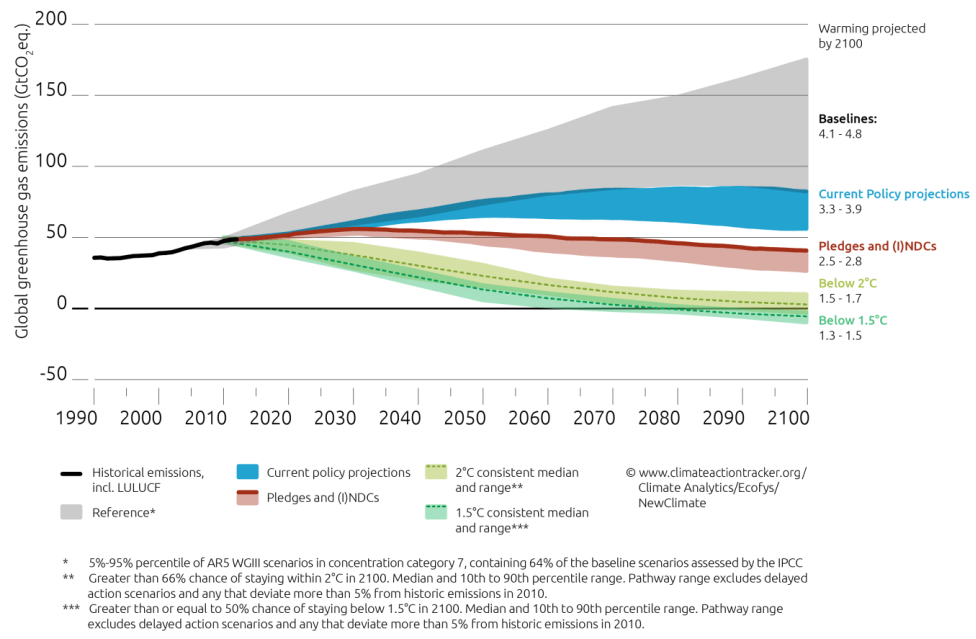

The Paris Climate Agreement alone will not solve the climate change problem (meaning we need even more action, not less). It puts us on the right track, though.

See the Climate Action Tracker website for details.

Figure — Expected emissions projections based on NDC commitments and current policies with corresponding temperature rise (right). Source: Climate Action Tracker

Ken Caldeira, Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science:

The US emits over 5 GtCO2 per year, or approximately 1.5 GtC [billions of tons of carbon] per year. Each GtC heats the Earth by about 0.002°C. Over a century (if there are no emission increases), this would be about 0.3°C, so Trump is in the right ballpark regarding effects of our direct emissions under optimistic assumptions regarding climate sensitivity and future US emissions under a business-as-usual scenario.

However, President Trump’s statement does not take into consideration the key role for US leadership. About 80% of emissions this century are expected to come from newly industrializing countries that are much less wealthy than the United States. It is hard to see how the United States can expect the rest of the world to develop along low-carbon-emission pathways if the United States is not leading by example. The effect of US leadership on global emissions could easily be 10 times more important than the direct effect of our own emissions.

Nearly 25 years ago, Republican President George H. W. Bush signed the UN Framework Convention and said “I am confident the United States will continue to lead the world in taking economically sensible actions to reduce the threat of climate change.” Apparently, President’s Bush’s confidence was misplaced.