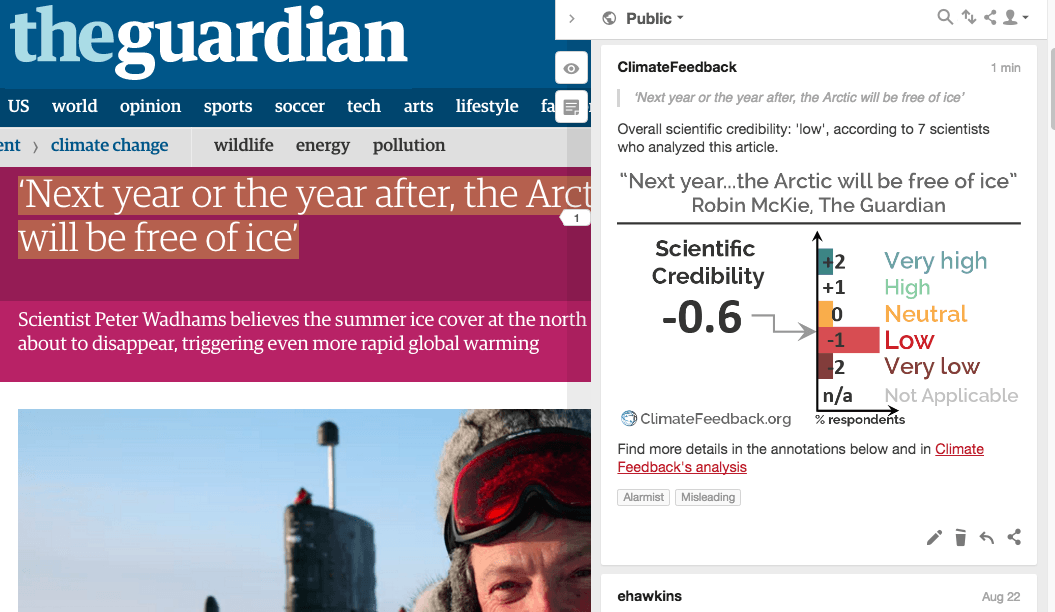

Seven scientists analyzed the article and estimated its overall scientific credibility to be ‘low’. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Alarmist, Misleading.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

The Guardian published an interview with Peter Wadhams, who discusses the consequences of human-induced global warming on Arctic climate and opines that “Next year or the year after, the Arctic will be free of ice”. This claim appears not to be supported by proper scientific argumentation based on evidence and a physical understanding of how that forecast would realize, either in the article or in previously published scientific papers.

The scientists who have reviewed the article indicate that while some statements are science-based, several claims are inaccurate or are opinions unsupported by current science. Most of the scientists tagged the article as ‘alarmist’ (meaning that “it overstates or exaggerates the risks of climate change”) and most indicated that the title of the article is not properly supported by its content. Widely publicizing this kind of guess, which has a low probability of turning out to be true, risks undermining public trust in science.

Note: scientists’ ratings are intended to assess the credibility of the information contained in an article, regardless of whether a journalist or an “expert” is the author.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

GUEST COMMENTS

Kyle Armour, Assistant Professor, University of Washington:The article contains numerous statements that are not supported by the scientific literature, but instead appear to be the personal opinion of Professor Wadhams. It is difficult to provide any meaningful rating for such an interview piece — Wadhams has the right to share his opinions when asked (however unsupported they may be) and at times even makes it clear that his statements are far outside the scientific mainstream. But I give the article low marks overall since it makes no attempt to distinguish which statements are rooted in science and which are simply speculation.

Ed Hawkins, Principal Research Fellow, National Centre for Atmospheric Science:Peter Wadhams’ views are well known to lie far outside the scientific mainstream. He makes several statements that are inaccurate and some are alarmist. There is no balance in the article from a more mainstream scientist.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

The interview/article should make it clearer that the claim by Prof Wadhams that the Arctic sea ice will be gone this year or next is at odds with mainstream climate science on that topic, and that he has repeatedly made such predictions that haven’t been borne out by subsequent observations. One could argue that climate model projections regarding Arctic sea ice are dire enough that there is no need to repeatedly provide unsubstantiated “guesstimates” of imminent collapse, and that doing so might even detract the public from the slower, but all too real, steady decline in sea ice, or even worse, that it eventually decreases the public’s trust in climate scientists.

Allen Pope, Research Associate, National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado Boulder:

I gave the “low” rating because the article’s discussion of expected Arctic sea ice retreat is misleading and inaccurate. The statements are not solidly based on the most up to date science.

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:

While the basic topics mentioned in the article are important to address, some of the statements are misleading and alarmist and the article is more of an opinion piece than a science-supported point.

The question concerning sea ice is tricky due to the many and complex factors involved, and the lack of good ice models that embody all scales involved.

Patrick Grenier, Specialist in climate scenarios, Ouranos:

This interview article covers and links several issues (sea ice projections, seabed methane bubbling, carbon capture, etc.), and I agree with some of the messages. The central claim, as conveyed by the title, is that disappearance of the summer Arctic sea ice cover will occur either in 2017 or in 2018.

This is not what most sea ice experts consider. Before propagating a marginal view, one should ensure having a very strong argumentation; in this interview no argumentation is put forward to support Peter Wadhams’ central claim. The journalist has chosen to interview a researcher known for having made wrong predictions in the past, and he has chosen not to balance Wadham’s view against that of other sea ice experts. Wadhams’ alarmism is potentially harmful, because when such spectacular predictions are not realized some people may perceive the whole scientific community or science itself as untrustworthy.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

The statements quoted below are from Peter Wadhams; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Ice-free means the central basin of the Arctic will be ice-free and I think that that is going to happen in summer 2017 or 2018.”

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

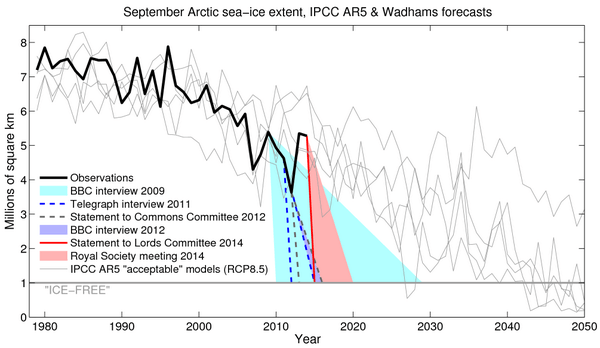

Readers should be reminded that under a business-as-usual greenhouse gas emissions scenario, climate models project an “ice-free” (less than 1 million km2 of ice) Arctic in September by ~2050. Peter Wadhams claims almost every year that it will happen sooner than that, in a matter of a few years – implying some total collapse of Arctic sea ice. This hasn’t happened so far, even if Arctic sea ice is decreasing a bit more rapidly than most models predict. I am borrowing this telling graph from Ed Hawkins (more details in this post):

Kyle Armour, Assistant Professor, University of Washington:

There is no reason to believe that the sea ice cover will disappear this quickly. Our best estimate for this comes from climate models projections, which show that the Arctic could become ice free (less than a million square km) by mid-century — at the earliest — under business-as-usual emissions. Observations show that sea ice is declining somewhat faster than models predict, but even accounting for this suggests that an ice-free Arctic is decades away.

Patrick Grenier, Specialist in climate scenarios, Ouranos:It is not clear whether a permanent or a one-year phenomenon is meant here (probably the former), but in any case the scientific support for the claim is weak.

- In the former case (permanent disappearance), this would not correspond to what most sea ice experts do consider. Indeed, section 11.3.4.1 of the last (2013) IPCC assessment report suggests a very low probability for permanent disappearance within the current decade. In fact, from the scientific literature it seems the phenomenon is more likely to take place during the period 2040-2060. Of course, a very low probability does not necessarily mean a zero probability, and IPCC’s report could possibly underestimate the odds for disappearance within the next few years. But before propagating a marginal view (relative to IPCC conclusions), one should ensure having a very strong argumentation; in this interview no argumentation is put forward to support Peter Wadhams’ central claim.

- In the other possible case (isolated single-year disappearance), it has to be said sea ice has strong year-to-year variability superimposed on its long-term declining trend, and no one has the tools to precisely predict the outcome one year in advance. Seasonal-to-decadal prediction groups equipped with physically-based models have some potential prediction skill for lead times up to 12-24 months, but they currently cannot guarantee to be right for any specific forecast (e.g.: Seasonal Forecasts of the Pan-Arctic Sea Ice Extent Using a GCM-Based Seasonal Prediction System and Pan-Arctic and Regional Sea Ice Predictability: Initialization Month Dependence). So, if it turns out in 2017 or 2018 that Wadhams was right, it will have been luck more than justified certainty.

Ed Hawkins, Principal Research Fellow, National Centre for Atmospheric Science:“Next year or the year after that, I think it will be free of ice in summer and by that I mean the central Arctic will be ice-free. You will be able to cross over the north pole by ship. There will still be about a million square kilometres of ice in the Arctic in summer but it will be packed into various nooks and crannies”

Professor Wadhams has been making this type of prediction in the media for several years, but they have not been borne out by the subsequent observations. For example: Telegraph, 2011 – “ice free by 2015”; Guardian, 2012 – “ice free by 2015 or 2016”; Financial Times, 2013 – “ice free no later than 2015”.

Allen Pope, Research Associate, National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado Boulder:I would also add that predictions of an ice-free Arctic (also defined as ~1 million square kilometers of remaining ice) are shown to be subject to quite a bit of uncertainty stemming from natural variability – on the order of about two decades.

“Most people expect this year will see a record low in the Arctic’s summer sea-ice cover.”

Ed Hawkins, Principal Research Fellow, National Centre for Atmospheric Science:

This is incorrect. The SIPN team (Sea Ice Prediction Network) have collected forecasts from 40 international groups and none are predicting a record low in 2016.

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:“People tend to think of an ice-free Arctic in summer in terms of it merely being a symbol of global change.”

This is a good point. Changes in one part of the Earth system due to warming are not in isolation and result in feedbacks in other parts of the Earth system.

“One key effect will be albedo feedback”

Rasmus Benestad, Senior scientist, The Norwegian Meteorological institute:

Albedo is one effect, but it is moderated by cloud cover and only is effective during summer (winter gives dark “polar nights”). Other – perhaps equally important – factors involve the effect open sea has on exchange of moisture, the way temperature varies with height, cloud cover …

Kyle Armour, Assistant Professor, University of Washington:“These effects could add 50% to the impact of global warming that is produced by rising carbon emissions.”

The sea-ice albedo feedback is thought to contribute about 10% to global warming (it’s the smallest of the various climate feedbacks); that’s including the impact of Antarctic sea-ice loss as well. So this estimate of 50% for Arctic sea-ice loss alone seems far too high.

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:These effects are admittedly included in climate models projections (even though sea ice disappears later in these models than Wadhams suggests here). What Wadhams is describing here is useful to understand these projections, but it doesn’t mean that these effects will come on top of current projections.

“Russian scientists who have investigated waters off their coast have detected more and more plumes of methane bubbling up from the seabed.”

Ed Hawkins, Principal Research Fellow, National Centre for Atmospheric Science:

However, there is evidence from a dedicated field campaign that the methane in ocean plumes does not affect the atmosphere: Extensive release of methane from Arctic seabed west of Svalbard during summer 2014 does not influence the atmosphere

Jeremy Fyke, Postdoctoral researcher, Los Alamos National Laboratory:“Underneath the permafrost there are sediments full of methane hydrates. When the permafrost goes, you release the pressure on top of these hydrates and the methane comes out of solution”

It’s unclear what is meant by ‘permafrost goes’. Nothing particularly ‘goes’ anywhere, it just melts (and has been naturally melting due to post-Last Glacial Maximum sea level rise and the resulting thermal flux due to shelf inundation). Consequentially, I would not expect the pressure seen by the underlying hydrates to decrease if the overlying permafrost degrades. In fact in the real world it will probably increase due to anthropogenic sea level rise. So it will necessarily be an anthropogenic temperature pulse, not a pressure pulse that will destabilize methane hydrates under relic permafrost.

Finally, methane molecules in hydrates is not ‘in solution’ but rather in the hydrate crystalline lattice.

“The most recent prediction of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is that seas will rise by 60 to 90 centimetres this century. I think a rise of one to two metres is far more likely.”

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:

This range is not entirely accurate. Using different climate scenarios, global mean sea level is predicted to rise by 0.26 to 0.98 m by the end of the century. This does not include potential collapse of marine-based sectors of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, which could raise these estimates. Recent work suggests that Antarctica’s contribution to sea level could contribute more than 1 m to sea level rise on top of the IPCC AR5 estimates.

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:“the first scientists to show that the thick icecap that once covered the Arctic ocean was beginning to thin and shrink.”

Arctic sea ice is typically less than 4 m thick.

The use of ‘ice cap’ traditionally implies a body of ice on land that covers less area than an ice sheet; however, the article discusses sea ice, not an ice cap, which is floating ice that forms due to freezing of surface water.

Jeremy Fyke, Postdoctoral researcher, Los Alamos National Laboratory:This is a misleading term. Ice caps are technically large land-based glaciers, whereas I think ‘Arctic icecaps’ here mean Arctic sea ice.

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:“‘Next year or the year after, the Arctic will be free of ice’”

The title is misleading. Wadhams suggests that the central Arctic (only) will be ice free in the summer.