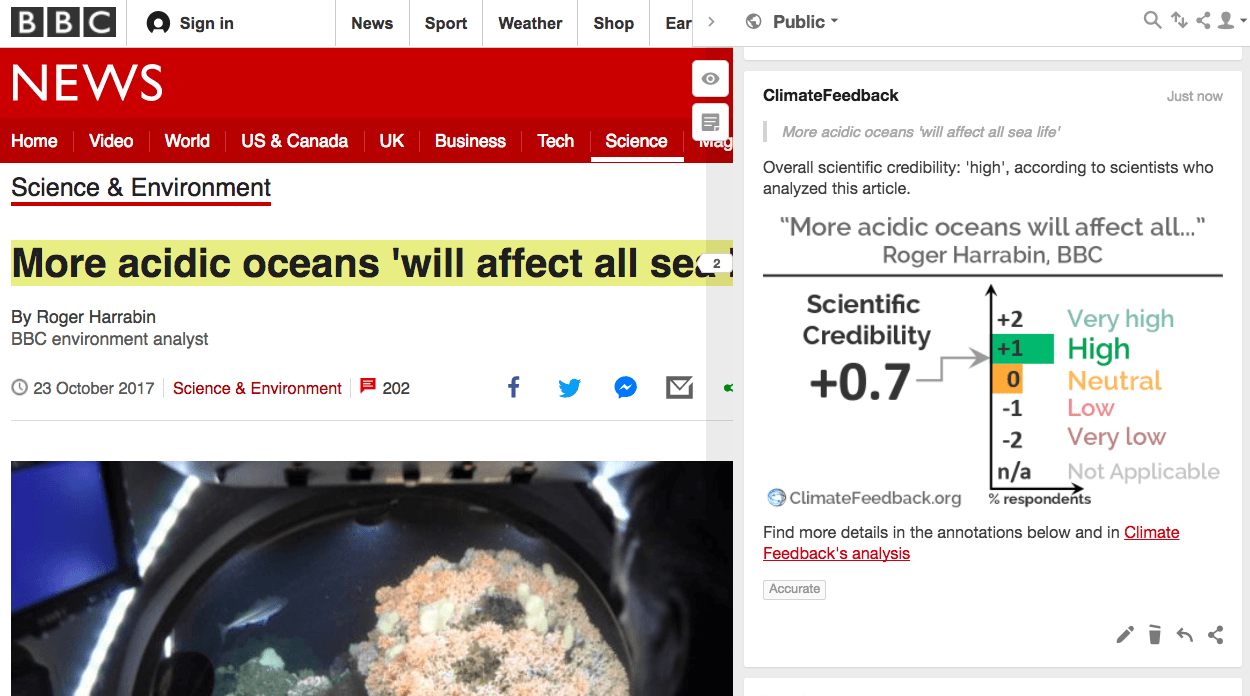

Three scientists analyzed the article and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be 'high'. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Accurate.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This BBC article describes an as-yet-unreleased report on ocean acidification from a major collaborative scientific project called BIOACID. The report will summarize the state of research on the impacts of ocean acidification—the changing pH and chemistry of seawater due to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide—on marine life.

Scientists who reviewed the article found that it was generally accurate in its description of the forthcoming report’s overall conclusions that ocean acidification poses an important threat to marine ecosystems. However, the BIOACID report will cover a broad and complex field of research, very little of which is explained in this short article.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Lennart Bach, Postdoctoral research fellow, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel:

A good summary of BIOACID’s key results. The information provided here is based on peer-reviewed scientific articles. I am glad the author mentions the statement that “[…]even if an organism isn’t directly harmed by acidification it may be affected indirectly through changes in its habitat or changes in the food web.” I think these complex (and so far poorly understood) food web interactions deserve attention by both the public and the scientific community. It is also important that the author mentions that there are potential winners (e.g. macroalgae) in an acidified ocean and that not every organism is negatively affected.

Jean-Pierre Gattuso, Research Professor, CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie and IDDRI:

The German program BIOACID has generated an impressive amount of knowledge on ocean acidification and its impacts. The BBC article is based on a brochure that is not available to me. It does not contain any inaccuracies but only skims the surface of the issue by highlighting a few scientific results with just one sentence. The synthesis of more than 350 publications on the effects of ocean acidification alluded to would deserve an in-depth article to provide important insight and better explain implications of the science.

Adam Subhas, PhD candidate, Caltech:

This article is a well-done presentation of a newly published long-term study on ocean acidification. Such studies are useful for documenting long-term, larger-scale effects and the author seemed to do a pretty good job in stating the findings accurately.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

FEATURED ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“More acidic oceans ‘will affect all sea life’”

Lennart Bach, Postdoctoral research fellow, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel:

“More acidic” is not entirely correct as the ocean is strictly speaking still alkaline (pH>7) and will remain so in the future. It is nevertheless true that the pH will most likely decrease (and has already done so in the past). A small change in the pH leads to large shifts in seawater carbonate chemistry (as the author correctly mentions later in the main text).

The pH change will affect many species. I am not sure if the statement “all sea life” is justified at this stage. Indirect effects will likely play a major role here (as mentioned later in the text) but this still lacks evidence. This is more like “work in progress” I would say.

“Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the average pH of global ocean surface waters have fallen from pH 8.2 to 8.1. This represents an increase in acidity of about 26%.”

Lennart Bach, Postdoctoral research fellow, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel:

Correct.

“This means the number of baby cod growing to adulthood could fall to a quarter or even a 12th of today’s numbers, the researchers suggest.”

Lennart Bach, Postdoctoral research fellow, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel:

This statement is based on on a study by Stiasny et al*. The authors write: “Here, we obtain first experimental mortality estimates for Atlantic cod larvae under OA and incorporate these effects into recruitment models. End-of-century levels of ocean acidification (~1100 μatm according to the IPCC RCP 8.5) resulted in a doubling of daily mortality rates compared to present-day CO2 concentrations during the first 25 days post hatching (dph), a critical phase for population recruitment. These results were consistent under different feeding regimes, stocking densities and in two cod populations (Western Baltic and Barents Sea stock). When mortality data were included into Ricker-type stock-recruitment models, recruitment was reduced to an average of 8 and 24% of current recruitment for the two populations, respectively. Our results highlight the importance of including vulnerable early life stages when addressing effects of climate change on fish stocks.”

The author of the BBC article referred to their work correctly.

- Stiasny et al (2016) Ocean Acidification Effects on Atlantic Cod Larval Survival and Recruitment to the Fished Population, PLOS ONE

“[Riebesell] is a world authority on the topic and has typically communicated cautiously about the effects of acidification.”

Adam Subhas, PhD candidate, Caltech:

This is good to note, as it shows that scientists directly involved in the research are driven by these experiments to speak out about these effects now.

“‘But even if an organism isn’t directly harmed by acidification it may be affected indirectly through changes in its habitat or changes in the food web.’”

Lennart Bach, Postdoctoral research fellow, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel:

A very important statement which is often neglected. It is good that the author included this statement.

“And some plants – like algae which use carbon for photosynthesis – may even benefit.”

Lennart Bach, Postdoctoral research fellow, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel:

This sentence is not really wrong but imprecise. First, plants use carbon dioxide (or in the case of aquatic photosynthetic organisms CO2 and often bicarbonate). The term “carbon” is too general. Second, the sentence implies that only some plants use carbon dioxide. I am sure the author is aware that “all” plants use CO2 for photosynthesis.

Adam Subhas, PhD candidate, Caltech:

The use of “carbon” here is confusing. However the statement is not totally wrong. It is fine in my opinion to say “some plants maybe benefit” because experiments have only been run on some types of plants and algae.