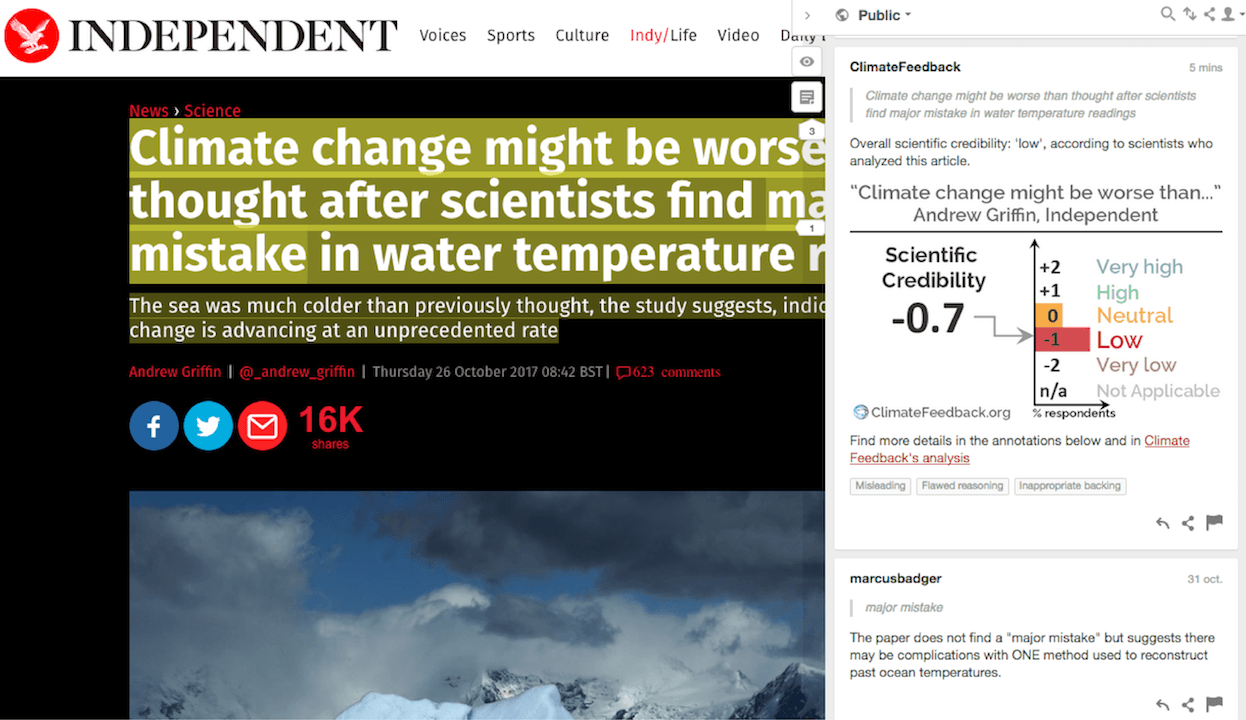

Three scientists analyzed the article and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be 'low'. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Flawed reasoning, Inappropriate sources, Misleading.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This article in The Independent describes a study examining one type of “proxy” record for past global temperatures the geologic record. The study found a potential problem with temperature estimates for time periods tens of millions of years ago, but this article concludes that the study means current climate change is “far worse than previously calculated”.

Scientists who reviewed the article explained that this conclusion is not logically connected to the contents of the study. The article exaggerates the study’s implications for records of past climate—there are multiple types of proxy records that have been used to study those time periods— and invents implications for future warming.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Marcus Badger, Lecturer in Earth Sciences, The Open University:

The article reports on a paper which suggests there may be complications with ONE method we use to determine past ocean temperature. Notwithstanding possible flaws in the methods of the paper, the article ignores significant evidence from other measurements and observations and tells us nothing directly about the severity of future and present climate change.

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

This article takes the results of an experiment and, fuelled by some irresponsible hyperbole from the authors of the study, extrapolates incorrectly to modern climate change. The tone of the article is overly alarmist and unfounded based on the study in question.

Mitch Lyle, Professor, Sr. Research, Oregon State University:

The article has minor inaccuracies reporting a flawed study. The original study has defects. If all the past records of climate warming via oxygen isotopes were wrong, they would need to be buried to the same depth (or at least to the same temperature) to get the common overprint. Depth of burial varies by a huge amount. The study also fails to acknowledge that oxygen isotopes are only one way used to measure ocean temperature.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

FEATURED ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Climate change might be worse than thought after scientists find major mistake in water temperature readings The sea was much colder than previously thought, the study suggests, indicating that climate change is advancing at an unprecedented rate”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

This title and subtitle are totally misleading. The question of whether or not some (and I stress some because this only affects one proxy, not the others that suggest warm temperatures) temperature estimates were wrong has no bearing at all on the rate of current climate change.

Marcus Badger, Lecturer in Earth Sciences, The Open University:

Even if it were correct, there is no direct link between our understanding based on the method discussed in the paper and our understanding of the severity of future and present climate change.

The paper does not find a “major mistake” but suggests there may be complications with ONE method used to reconstruct past ocean temperatures.

“The research challenges the ways that researchers have worked out sea temperatures until now, meaning that they may be increasing quicker than previously suggested.”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

I don’t think there’s a link between alteration of deeply buried sediments in this study (i.e., oxygen isotope measurements from millions of years ago) and current rates of temperature increase (directly measured from satellites and weather stations). It may challenge the way we work out sea temperatures (although as I will note later the paper seriously overstates its case), but this doesn’t change the observed rates of change in the post-industrial era. This is inaccurately presented.

Marcus Badger, Lecturer in Earth Sciences, The Open University:

There is no link between the method the paper studies to construct past temperature changes (oxygen isotopes in foraminifera) and present temperature increase (measured using satellites, direct measurements and other proxies).

“If true, that means that the global warming we are currently undergoing is unparallelled within the last 100 million years”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

The study suggests some periods of time may (according to one proxy) be cooler than originally thought, but this doesn’t change the “rate” of warming seen today. This isn’t anything to do with the study. There are confused messages coming out here about rate of change vs. absolute values. Certainly we are not reaching temperatures today that are warmer than over the last 100 million years, either with or without the results of this study.

“and [current global warming is] far worse than we had previously calculated.”

Marcus Badger, Lecturer in Earth Sciences, The Open University:

This does not follow logically from the previous sentences.

“But [ocean temperatures 100 million years ago] might in fact have stayed relatively stable”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

“Relatively” being the operative word here. And in any case, there is evidence of warmer poles from other proxies besides oxygen isotopes—organic biomolecule-based proxies (like TEX86), for example. Quite aside from that, there were lush forests where today there is only ice. The fact that the poles were warmer is not something to be called into question by this one study on one proxy, on one type of foraminifera subjected to very high temperatures in the lab. I don’t suggest that this can’t be operating on oxygen isotopes at some level, but given the wealth of other evidence, I suggest the authors of this study, and subsequently the author of this piece, have gone well overboard with their assessment.

“‘If we are right, our study challenges decades of paleoclimate research,” said Anders Meibom, the head of EPFL’s Laboratory for Biological Geochemistry and a professor at the University of Lausanne.”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

It seems the authors of this paper are not au fait with the decades of work that has been done with other proxies that also show warmth at these times, since they take their observed changes in oxygen isotopes in deeply buried and heated sediments, and extend their results outrageously, discounting hundreds of papers on either shallow, well-preserved samples, or organic temperature proxies, or pollen assemblages, or leaf margin analysis, or clumped isotopes—all of which show that the poles were indeed warmer at this time.

Marcus Badger, Lecturer in Earth Sciences, The Open University:

It only potentially challenges ONE method used to reconstruct past temperatures. Other methods and observations based on biomarkers, pollen, large fossils support a much warmer ocean at this time.

“Until now, scientists have calculated the temperature of the ancient seas by looking at foraminifera, the fossils of tiny marine organisms found in the sediment on the ocean floor.”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

This is only one way that scientists have calculated the temperature of the ocean, and they will continue to do so.

“But the new research shows that the amount of oxygen in those shells doesn’t actually remain constant over time.”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

It’s nothing to do with the amount of Oxygen. It’s CaCO3, so oxygen content is pretty much fixed—it’s the isotopic ratio of the oxygen that is incorporated.

Marcus Badger, Lecturer in Earth Sciences, The Open University:

This is a misunderstanding of the way that oxygen isotopes work.

“The new research showed that [oxygen isotopes in foraminifera] can change”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

There is not enough information here. This research specifically only showed that they could change when heated to 300˚C. By not saying what the circumstances are under which the temperature estimates can be altered, the article throws undue doubt on what is in most settings (despite what the authors of the study seem to be suggesting) pretty robust.

“This means that the paleotemperature estimates made up to now are incorrect”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

This is a huge overstatement. It in fact means that some paleotemperature estimates made up to now may be incorrect. An interesting finding, but being over-stated in the extreme.

“The changes in the amount of oxygen in the shells isn’t a reflection of changing temperatures – just a consequence of the fact that the amount of oxygen seen changes over time anyway.”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

It doesn’t just change over time anyway. Firstly, we are talking about the isotope ratio of oxygen, not the amount. Secondly, the authors show evidence that in some depositional settings this sort of “resetting” of temperatures could occur. By over-simplifying here the author of the article loses and obscures the original study.

“To revisit the ocean’s paleotemperatures now, we need to carefully quantify this re-equilibration, which has been overlooked for too long. For that, we have to work on other types of marine organisms so that we clearly understand what took place in the sediment over geological time”

Michael Henehan, Postdoctoral Researcher, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam:

Or use other temperature proxies to compare with the oxygen isotope data to see if they are consistent—which is what has been done for years.

Marcus Badger, Lecturer in Earth Sciences, The Open University:

There are already other methods based both on different organisms and different proxy methods which the authors ignore.