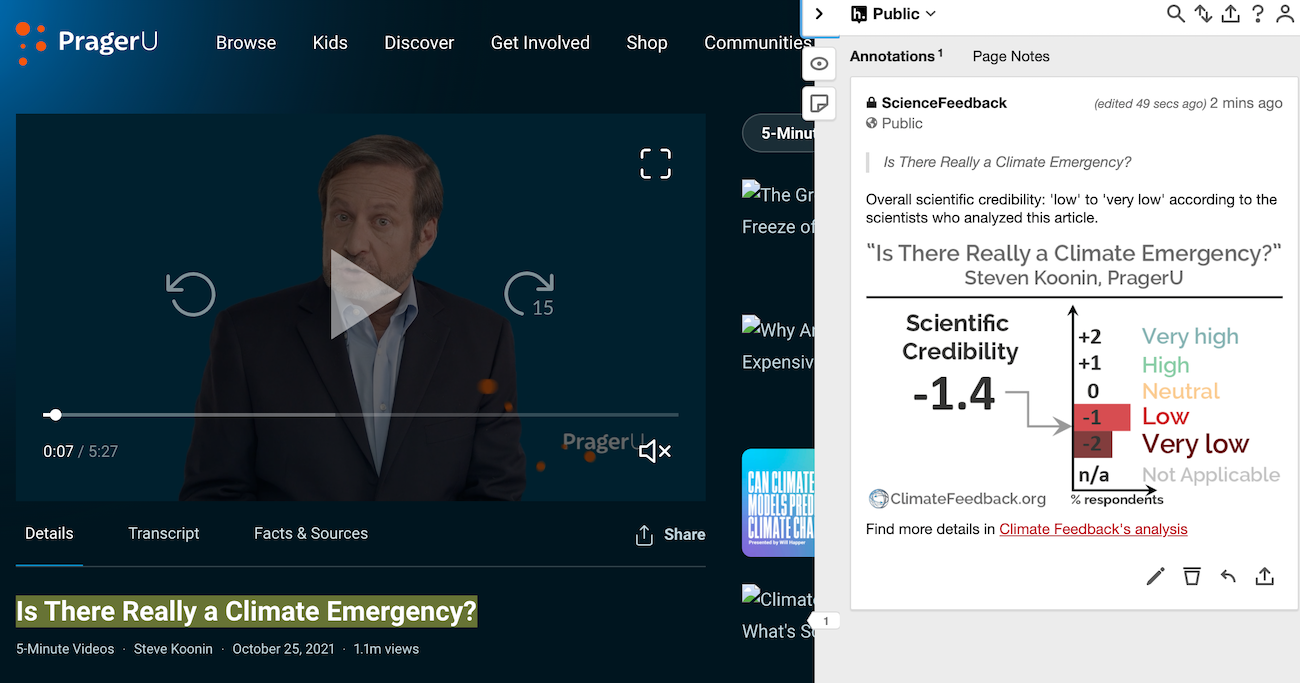

Nine scientists analyzed the video and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be low to very low. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Inaccurate, Misleading.

SUMMARY

A popular PragerU video (viewed more than 1 million times) outlines a range of claims on climate change by Steve Koonin, a theoretical physicist and professor at the New York University Stern School of Business. The claims, many of which Koonin has previously stated in his book, “Unsettled,” seek to downplay the severity of a range of climate findings.

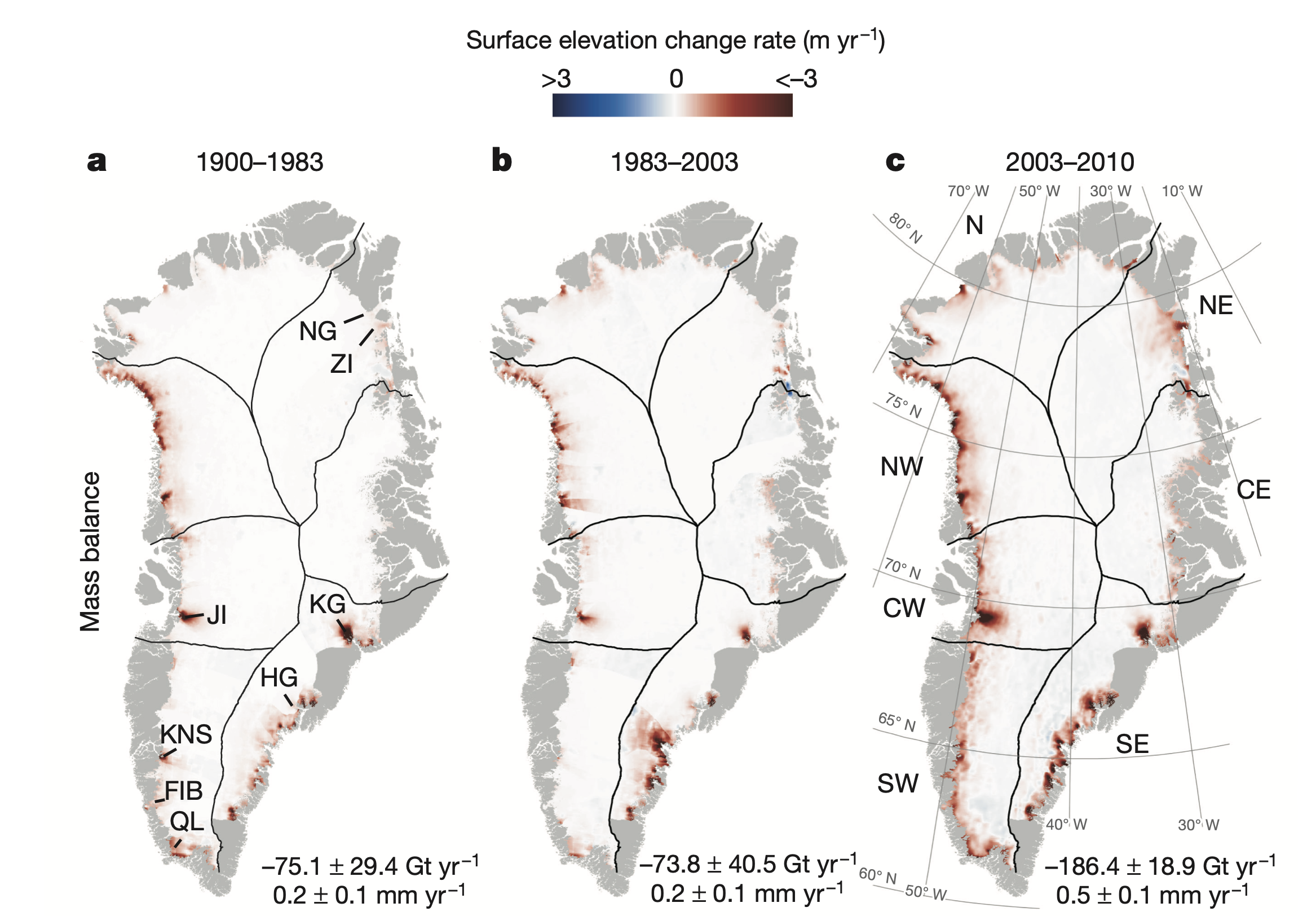

Scientists who reviewed the post – some of whom have reviewed past claims by Koonin – found inaccuracies among his claims. “Many statements are misleading and others are simply incorrect,” said Justin Schoof, director of the School of Earth Systems and Sustainability at Southern Illinois University. As an example of a factually inaccurate statement, Koonin claims that “Greenland’s ice sheet isn’t shrinking any more rapidly today than it was 80 years ago”. In fact, as Climate Feedback noted in April 2021, “the per year average ice loss during 2003-2010 is roughly 2.5 times higher than during 1900-2003. Furthermore, this melting has generated a measurable sea level rise over the last 20 years.”[19]

Surface elevation change rates in Greenland during 1900-1983 (a), 1983-2003 (b), and 2003-2010 (c). The numbers listed below each panel are the integrated Greenland-wide mass balance estimates expressed as gigatonnes per year and as millimetre per year GMSL (global mean sea level) equivalents. From Kjeldsen et al. 2015.

“The Greenland Ice Sheet is currently melting at a rate comparable to (or greater than) any in the past 12,000 years, let alone 80 years ago,” Daniel Swain, climate scientist at the Institute of the Environment & Sustainability at UCLA, says.

Schoof points to Koonin’s claim that “government reports state clearly that heat waves in the US are now no more common than they were in 1900”. In fact, science shows heat waves are occurring more frequently and have become more intense as a result of climate change. The 2018 U.S. National Climate Assessment shows that the heat wave season in the United States has increased in length since the 1960s, and according to the Environmental Protection Agency, heat wave frequency has increased as well.[1]

This graph, from the 2018 National Climate Assessment, shows the upward trend in Heat Wave Season length in the United States. As the assessment states, “the season length of heat waves in many U.S. cities has increased by over 40 days since the 1960s. Hatched bars indicate partially complete decadal data.”

Heat waves have also increased globally, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report states:[2]

“It is virtually certain that hot extremes (including heatwaves) have become more frequent and more intense across most land regions since the 1950s, while cold extremes (including cold waves) have become less frequent and less severe, with high confidence that human-induced climate change is the main driver of these changes.”

Climate contrarians have been known to try to confuse viewers by cherry-picking local or regional cases in an attempt to undermine these findings. Koonin is doing that here by focusing on a time series that includes the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, which was exacerbated by poor land use and years of drought and brought about heat waves that “remain the most severe in recorded U.S. history,” according to the EPA.

“Parts of the early 20th century, particularly the 1930s, were very warm in the United States”, Schoof explains. “This was regional rather than global, but can be used to make recent changes in the US seem less relevant than they are”.

Koonin also makes a claim about hurricane activity, stating that it “is no different than it was a century ago”. Research shows the opposite: Knutson et al (2019) found that tropical cyclone activity had changed over the last several decades, and that human-caused climate change was likely playing a role in these changes[3]. As Kevin Walsh, co-author of the study and a professorial fellow at the School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Melbourne notes, the study found that tropical cyclones have increased in intensity in recent decades, and the proportion of very intense tropical cyclones has increased globally. Among other findings, the study also concluded that intense precipitation events associated with tropical cyclones in the Gulf of Mexico are on the rise.

“It was also concluded that these changes were likely due to anthropogenic climate change,” Walsh continues. “So I’m not sure how this leads the author to state that there has been no change in hurricane activity in the last 100 years.”

The physics of hurricanes also make scientists expect that climate change will continue to influence their strength and the amount of rain they generate: Knutson et al (2021) found that “the proportion of category 4-5 storms (winds 58 m/s or higher) is projected to increase substantially under a warming climate”.[4]

Koonin makes a similar claim about flooding, stating that “floods have not increased across the globe over more than seventy years”. This statement – as well as many other statements in the post – is a result of cherry-picking data, says Mark Richardson, Research Associate at Colorado State University/NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It’s true that, while scientists have determined that extreme precipitation is on the rise globally due to climate change, they are still working to determine exactly how those precipitation extremes will impact flooding risk.[5]

However, Richardson notes that there are several kinds of floods – including flash flooding, coastal flooding and river flooding. In the United States, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that, over the last several decades, “annual frequencies of high tide flooding are found to be linearly increasing in 31 locations (out of 99 tide gauges examined outside Alaska) mostly along the coasts of the Northeast/Southeast Atlantic and the Eastern/Western Gulf of Mexico, and to a lesser extent, along the Northwest and Southwest Pacific coasts”.[7] And Richardson cites the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report in stating that, even as some regions become drier, “the general tendency is therefore higher flash-flood risk (our recent work supports this)”.[2,8]

“Dr. Koonin chooses not to report the increased flash or coastal flooding risk, but instead states that global floods haven’t increased,” Richardson continues. “This is not supported by the report he claims to be using.”

Koonin points out that clouds play a big role in our climate, and that, because we can’t predict global cloud coverage “say 10, let alone 50 years from now,” climate models are built on a “shaky foundation”. Koonin is correct that clouds, which can have both a warming and a cooling effect on the planet, are an important part of understanding the climate and remain a challenge for climate modelers.[9,10] However, that challenge does not negate the projections of our current climate models. “The truth is that cloud changes can only modulate warming, not stop or reverse it,” says Mark Zelinka, research scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. “There is no conceivable scenario in which cloud feedback prevents warming in the face of rising human emissions of greenhouse gases. In a world with rising CO2 emissions, how clouds respond determines whether the future is hotter or much hotter; steady or colder temperatures are simply off the table”.

Koonin also claims that “the media, the politicians, and a good portion of the climate science community attribute every terrible storm, every flood, every major fire to ‘climate change.’” Though it’s a subjective claim, it’s not accurate when it comes to the “climate science community,” Swain says. “In fact, an entire sub-field of climate and atmospheric science has developed in recent years specifically aimed at developing and implementing scientifically valid methods of attributing specific extreme events to climate change (known as ‘extreme event attribution.’)”.[11,12] That sub-field does not find that every extreme event can be tied to climate change – this CarbonBrief graphic, for instance, shows extreme events around the world that have been tied to climate change, and those that haven’t.

“It is the case that climate change is worsening many extreme weather events, particularly heatwaves, but this conclusion is founded on a large and growing number of peer-reviewed studies,” says Andrew King, ARC DECRA Fellow and Senior Lecturer in Climate Science at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes at the University of Melbourne.

Koonin claims that “Greenland’s ice sheet isn’t shrinking any more rapidly today than it was 80 years ago.” In fact, as Climate Feedback noted in April 2021, “the per year average ice loss during 2003-2010 is roughly 2.5 times higher than during 1900-2003. Furthermore, this melting has generated a measurable sea level rise over the last 20 years.”[19]

“The Greenland Ice Sheet is currently melting at a rate comparable to (or greater than) any in the past 12,000 years, let alone 80 years ago,” Swain says.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

Mark Richardson, Research Associate, Colorado State University/NASA JPL:

The author of this video, Dr. Steven Koonin, says he is following the scientific reports published by the UN and US government, but by subtly changing wording and choosing not to mention important context this video is very likely to mislead readers.

This style of selective wording and lack of context, an approach called “cherry picking”, applies to every one of Dr. Koonin’s scientific comments.

Justin Schoof, Professor and Chair, Southern Illinois University:

Many statements are misleading and others are simply incorrect.

Mark Zelinka, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:

I believe most of Dr. Koonin’s talking points have been refuted in several other places, most notably here on climatefeedback.org.

It appears as though most of the PragerU talking points are the same as those in his book and have not been updated to reflect being repeatedly corrected by the climate science community.

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

This video has many major errors and it is difficult to review the veracity of many claims due to the lack of referencing of sources.

Ilissa Ocko, Climate Scientist, Environmental Defense Fund:

This piece is very misleading and uses borderline inaccurate/cherry-picked “facts” and flawed reasoning to make its case. For example, there is myriad evidence that many extreme weather events are intensifying and/or becoming more frequent in most parts of the world (see Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report Working Group I Chapter 11, 2021); the extent depends on the region and the type of event, and therefore sweeping generalities (e.g. global flooding) or cherry-picked examples (e.g. heat waves in the U.S) do not adequately convey the severity of climate change in impacting communities and ecosystems worldwide.

ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the video; comments are from the reviewers (and are lightly edited for clarity).

Claim: “For example, government reports state clearly that heat waves in the US are now no more common than they were in 1900.”

Justin Schoof, Professor and Chair, Southern Illinois University:

Many statements are misleading and others are simply incorrect. As a single example, there is a statement regarding heat waves in the U.S. being no worse than they were in 1900, according to government reports. Figure 1.2 of the 2018 U.S. National Climate Assessment clearly shows an increase in heat waves in recent decades. Heat waves are getting worse in the United States, especially in recent decades. Parts of the early 20th century, particularly the 1930s, were very warm in the United States. This was regional rather than global, but can be used to make recent changes in the US seem less relevant than they are. Lastly, we expect warming from greenhouse gases to impact minimum temperatures more than maximum temperatures and that’s exactly what’s happening. It makes for less dramatic warming in the maximums relative to the minimums.

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

There is now extensive evidence that heatwaves are increasing due to global warming, both globally and also specifically in the United States–and recent government reports (in addition to peer-reviewed research in other venues) reflect this. For example: The EPA and the National Climate Assessment. It is true that heatwaves in the United States, although they are indeed increasing in aggregate, have increased at a slower rate than across much of the rest of the globe. But the reality is that the United States is indeed experiencing more extreme heat today than it was decades ago.

Claim: “Hurricane activity is no different than it was a century ago.”

Kevin Walsh, Professor of Meteorology, University of Melbourne:

The most recent authoritative assessment of this particular issue (Knutson et

2019), of which I was a co-author, concluded the following (among other conclusions):

1. There has been a poleward migration of tropical cyclone tracks in the western North Pacific region.

2. There has been an increase in the global proportion of very intense tropical cyclones

in recent decades, as well as an overall increase in tropical cyclone intensity.

3. There has been an increased incidence of intense precipitation events associated with tropical cyclones in the Gulf of Mexico region.

It was also concluded that these changes were likely due to anthropogenic climate change.

So I’m not sure how this leads the author to state that there has been no change in hurricane activity in the last 100 years.

Kerry Emanuel, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, MIT:

[Comment from a previous evaluation of a similar claim.]

This statement is flat out wrong. In the first place, the theoretically predicted trends would not have been detectable in the sparse and noisy hurricane record until recently, and in fact they HAVE recently been detected. The most up-to-date research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences demonstrates an increase in the proportion of hurricanes that become major hurricanes (Category 3-5) globally, supporting theoretical predictions that date back to 1987 (see figure below).

The proportion of major hurricane intensities to all hurricane intensities globally from 1979-2017. Data is binned into 3-year periods. The proportion of global major hurricanes increased by 25% over the 39-year time period analyzed. From Kossin et al. (2020).[20]

Claim: “Floods have not increased across the globe over more than seventy years.”

Mark Richardson, Research Associate, Colorado State University/NASA JPL:

Regarding floods, there are several types including flash, coastal and river flooding. The UN report [2] states that heavy rain events have gotten more extreme and more common “over a majority of land regions with good observational coverage since 1950”, and although some regions dried, the general tendency is therefore higher flash-flood risk (our recent work supports this[7]). Meanwhile, at tide gauges scattered around Earth’s coasts there has been a “median 165% increase in high-tide flooding over 1995—2014 relative to 1960—1980”. Changes in high river levels depend on the region, but the data are sparse so there is “low confidence” in global changes. Dr. Koonin chooses not to report the increased flash or coastal flooding risk, but instead states that global floods haven’t increased. This is not supported by the report he claims to be using.

Claim: “Greenland’s ice sheet isn’t shrinking any more rapidly today than it was 80 years ago.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

The Greenland Ice Sheet is currently melting at a rate comparable to (or greater than) any in the past 12,000 years, let alone 80 years ago.

For more on this claim, see our article review from April 2021.

Claim: “The media, the politicians, and a good portion of the climate science community attribute every terrible storm, every flood, every major fire to “climate change.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

This statement is not a quantitative claim, but it appears to connote that scientists are systematically attributing extreme events to climate change without evidence. This is simply not correct. In fact, an entire sub-field of climate and atmospheric science has developed in recent years specifically aimed at developing and implementing scientifically valid methods of attributing specific extreme events to climate change (known as “extreme event attribution.”) It’s impossible to make a blanket statement about all kinds of extreme events (global warming is increasing the frequency and intensity of global heatwaves, for example, but decreasing the intensity of global cold snaps), but numerous scientists around the world now conduct research on this specific topic, and often find physically and statistically overwhelming evidence that climate change has increased the risk of specific events such as individual extreme heatwaves and extreme downpours (among other types of events).

Some overviews of how “extreme event attribution” is conducted, as well as examples of applications to specific events, include:

- https://www.cell.com/one-earth/fulltext/S2590-3322(20)30247-5

- https://www.nap.edu/read/21852/chapter/5

- https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate2657

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

This video has many major errors and it is difficult to review the veracity of many claims due to the lack of referencing of sources. Here, I’ll just focus on the claim that scientists, the media and politicians attribute every extreme event to climate change. A community of climate scientists has worked to develop a robust and comprehensive methodology for thorough analysis of how human-caused climate change affects extreme weather events.[10,11] This approach has indeed been used to demonstrate that there are often very large effects of human-caused climate change on some events, such as the Siberian heat event of 2020.[16] It is incorrect to say that scientists link climate change to every single extreme event as some studies have not identified a clear link to some extreme events (a comprehensive set of the findings of these studies can be found here). It is the case that climate change is worsening many extreme weather events, particularly heatwaves, but this conclusion is founded on a large and growing number of peer-reviewed studies.

Claim: “Natural fluctuations in the height and coverage of clouds have at least as much of an impact on the flows of sunlight and heat as do human influences. But how can we possibly know global cloud coverage say 10, let alone 50 years from now? Obviously, we can’t. But to create a climate model, we have to make assumptions. That’s a pretty shaky foundation on which to transform the world’s economy.”

Timothy Myers, Research Scientist, University of Colorado, Boulder / NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory:

These statements are very misleading and not logically coherent. While it is true that natural fluctuations in clouds can have impacts on the fluxes of heat and solar radiation as large or larger than those associated with climate change, this is neither a profound statement nor does it provide insight into how clouds will respond to planetary warming. To take another example, the natural fluctuations of Earth’s temperature in a given hemisphere from winter to summer are larger than the temperature rises due to human influences. But this tells us absolutely nothing about what the human influence on Earth’s temperature actually is.

Moreover, there is indeed large climate model uncertainty with respect to how certain cloud types will respond to climate change[8]. But observations, theory, and high-resolution cloud models collectively provide evidence for how a variety of cloud types will change as unabated global warming continues[12-15]). In general, multiple lines of independent evidence inform our understanding of the human influence on climate – we do not rely on climate models alone[12]. This variety of evidence overwhelmingly suggests that the world’s economy must phase out the use of fossil fuels to ensure that the planet remains hospitable to organized human life.

Mark Zelinka, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:

Koonin is correct that subtle variations in cloud height, amount, and reflectivity can strongly modify Earth’s ability to absorb sunlight and emit heat to space. He is also correct that the need to model the entire planet’s climate for centuries precludes simulating the very small-scale processes that are involved in cloud formation, and this means that assumptions must be made around clouds in models. The upshot of this is that climate models disagree on how clouds will respond to warming[9]. This is why a grand challenge in climate research is to determine the extent to which clouds can act as a feedback on global warming [21]. If, say, low-level highly reflective clouds increase in coverage as the planet warms, this will decrease the amount of sunlight absorbed by the planet and put the brakes on warming. But if these clouds decrease in coverage with warming, this will allow more sunlight to be absorbed, thereby exacerbating warming relative to what it would be if clouds didn’t change – a positive feedback.

There are, however, several key points left out of Koonin’s cloud argument.

- Koonin’s statements may lead you to believe that predictions of future warming are built on a house of cards, with everything resting on poorly-simulated clouds. The truth is that cloud changes can only modulate warming, not stop or reverse it[8]. There is no conceivable scenario in which cloud feedback prevents warming in the face of rising human emissions of greenhouse gases. In a world with rising CO2 emissions, how clouds respond determines whether the future is hotter or much hotter; steady or colder temperatures are simply off the table.

- Moreover, a plethora of evidence from detailed analyses of satellite cloud observations as well as very high resolution modeling (which do not require assumptions about key cloud processes) indicates that cloud changes provide an amplifying feedback[13][14[15][22][23]. This means that climate models, on average, predict the right sensitivity of climate to CO2 – around 3 C (5.4 F) for a doubling of CO2[12]. Moreover, satellite-based cloud records are now long enough that we can see trends that confirm many of the cloud responses that climate models predict to occur with warming [24][25].

- Finally, climate scientists do not blindly follow climate model projections. We are well-aware that uncertainties surrounding clouds affects our ability to know precisely what future warming holds, and focus on predictions from models that better match observations. This means down-weighting models that are very insensitive to CO2 as well as those that are too sensitive to CO2. The latest IPCC report[2] in particular does this for most if not all projections.

Summary: To correctly note that clouds lead to uncertainties in future climate prediction without simultaneously clarifying (1) that “no big deal” is not in the range of plausible futures (unless emissions are reduced), and (2) that a huge body of evidence now points to clouds providing an amplifying feedback on warming, is very misleading. To position oneself as a rogue truth-teller, bringing to light uncertainties that climate scientists are trying to bury or ignore despite abundant evidence to the contrary is, well, hubris.

Claim: “Projecting future climate is excruciatingly difficult. Yes, there are human influences, but the climate is complex. Anyone who says that climate models are “just physics” either doesn’t understand them or is being deliberately misleading.”

Mat Collins, Professor, University of Exeter:

This is a bit of a tricky one, I think. Much of what he says is at least partially true and the same points have been used to argue that we must urgently do something about climate change. It is really just the general dismissive tone and language of the piece. Deconstructing [this claim], for example,

- Yes making climate projections is complex

- He admits human influence

- Yes climate models do make approximations to the laws of physics

For a general rebuttal, I think I would invoke the precautionary principle. Yes we don’t know everything we would like to about the complex details of climate change but we know enough that we should do something about it.

Claim: “It takes centuries for the excess carbon dioxide to vanish from the atmosphere. So, any partial reductions in CO2 emissions would only slow the increase in human influences—not prevent it, let alone reverse it.”

Ilissa Ocko, Climate Scientist, Environmental Defense Fund:

An example of flawed reasoning is that while the author is correct that CO2 can last for a long time in the atmosphere, and therefore partial reductions would only slow the increase in warming (and not prevent or reverse it), this does not mean that reductions in CO2 are not beneficial compared to what would happen otherwise. In fact, it is the opposite; every ton of CO2 we emit can commit us to warming for generations to come, meaning that every ton we reduce can help us avoid warming for centuries as well. Further, emissions goals are not just to reduce CO2 emissions, but to achieve “net zero” emissions by midcentury (a state in which we are not adding CO2 to the atmosphere beyond what can be removed) and then ultimately achieving negative CO2 emissions (more CO2 removed from the atmosphere than added); these actions *would* prevent additional warming and could even reverse warming.

REFERENCES

- [1] Reidmiller et al. (2018) Chapter 1: Overview. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States, Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II.

- [2] IPCC (2021) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contributions of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- [3] Knutson et al. (2019) Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: Part I, Detection and attribution. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

- [4] Knutson et al. (2021) Climate change is probably increasing the intensity of tropical cyclones. Science Brief.

- [5] Swain et al. (2020) Increased Flood Exposure Due to Climate Change and Population Growth in the United States. American Geophysical Union.

- [6] Sweet et al. (2018) Patterns and Projections of High Tide Flooding Along the U.S. Coastline Using a Common Impact Threshold. NOAA Technical Report NOS CO-OPS 086.

- [7] Chinita et al. (2021) Global mean frequency increases of daily and sub-daily heavy precipitation in ERA5. Environmental Research Letters.

- [8] Zelinka et al. (2017) Clearing clouds of uncertainty. Nature Climate Change.

- [9] Zelinka et al. (2020) Causes of Higher Climate Sensitivity in CMIP6 Models. Geophysical Research Letters.

- [10] Van Oldenborgh et al. (2021) Pathways and pitfalls in extreme event attribution. Climatic Change.

- [11] Philip et al. (2020) A protocol for probabilistic extreme event attribution analyses. Advances in Statistical Climatology, Meteorology and Oceanography.

- [12] Sherwood et al. (2020) An Assessment of Earth’s Climate Sensitivity Using Multiple Lines of Evidence. Reviews of Geophysics.

- [13] Myers et al. (2021) Observational constraints on low cloud feedback reduce uncertainty of climate sensitivity. Nature Climate Change.

- [14] Ceppi et al. (2021) Observational evidence that cloud feedback amplifies global warming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- [15] Cesana et al. (2021) Observational constraint on cloud feedbacks suggests moderate climate sensitivity. Nature Climate Change.

- [16] Ciavarella et al. (2021) Prolonged Siberian heat of 2020 almost impossible without human influence. Climatic Change.

- [17] Swain et al. (2020) Attributing Extreme Events to Climate Change: A New Frontier in a Warming World. One Earth.

- [18] Trenberth et al. (2015) Attribution of climate extreme events. Nature Climate Change.

- [19] Kjeldsen et al. (2015) Spatial and temporal distribution of mass loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet since AD 1900. Nature.

- [20] Kossin et al. (2020) Global Increase in Major Tropical Cyclone Exceedance Probability over the Past Four Decades. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- [21] Bony et al. (2015) Clouds, circulation and climate sensitivity. Nature Geoscience.

- [22] Klein et al. (2017) Low-Cloud Feedbacks from Cloud-Controlling Factors: A Review. Surveys in Geophysics.

- [23] Bretherton (2015) Insights into low-latitude cloud feedbacks from high-resolution models. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A.

- [24] Marvel et al. (2015) External Influences on Modeled and Observed Cloud Trends. Journal of Climate.

- [25] Norris et al. (2016) Evidence for climate change in the satellite cloud record. Nature.