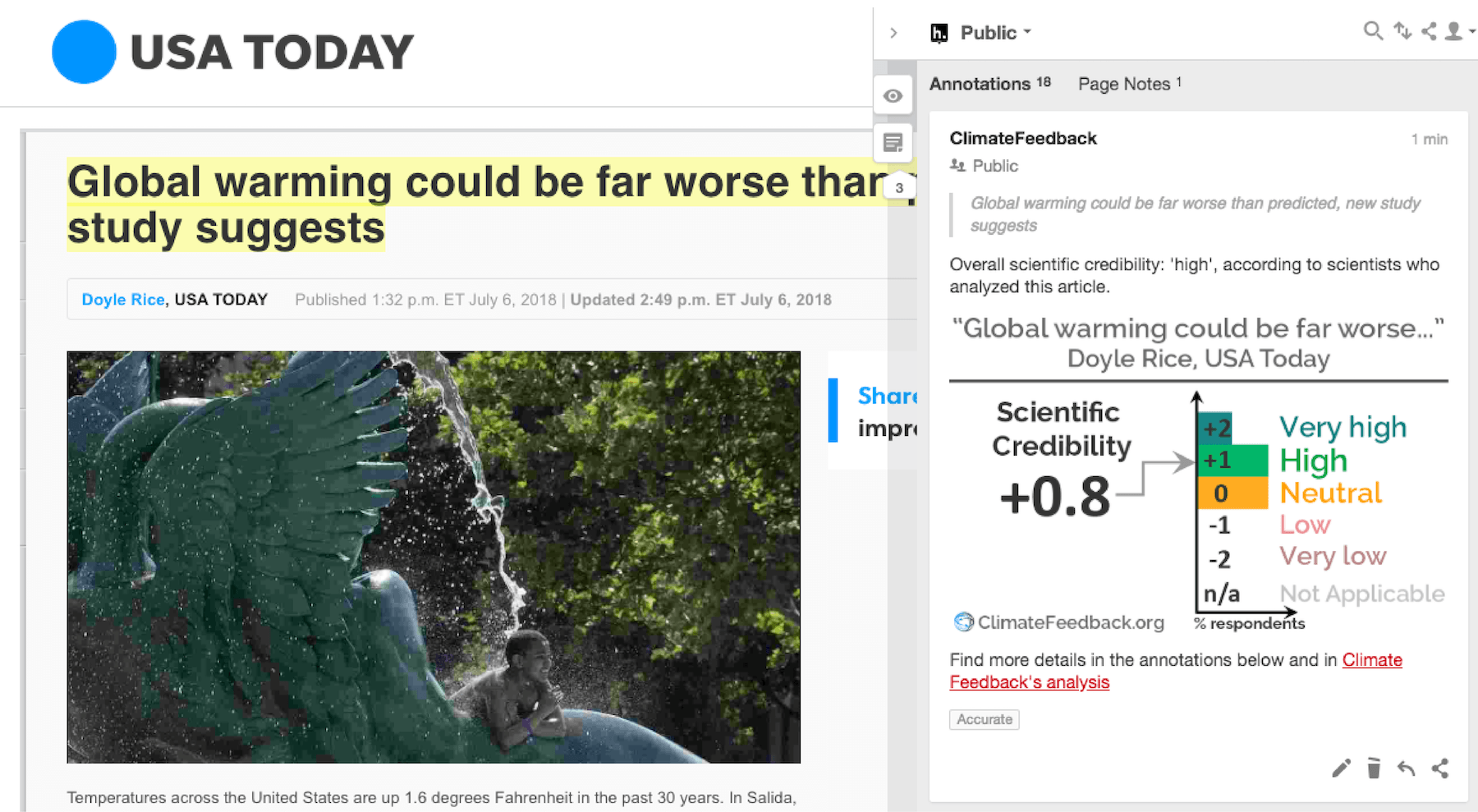

Five scientists analyzed the article and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be 'high'. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Accurate.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This story in USA Today covers a new study that compared past climate changes to model simulations, concluding that models can underestimate future warming over thousands of years.

Scientists who reviewed the article found that it described the study accurately. However, it implies relevance for projections of future climate change without making it clear to readers that this refers to projections far beyond the end of this century. The study does not indicate that the oft-discussed climate model projections of warming by 2100 are underestimated—an important distinction.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall assessment of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Willem Huiskamp, Postdoctoral research fellow, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:

This article accurately articulates how studying past climates as an analogue for present day warming can show how we may be underestimating the long-term equilibrium temperature rise of the planet.

The only thing missing is an extra sentence or two detailing the reason for the discrepancies between models and observations and a clearer expression of the time-scales considered (end of century vs millennia from now).

Kelly McCusker, Research Associate, Rhodium Group and Climate Impact Lab:

The article is accurate but could be improved with additional context, in particular emphasizing that the timescale over which the listed changes could occur is centuries-to-millennia.

Irene Brox Nilsen, Researcher, Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate:

I think the text accurately represents the current status of knowledge on projected climate change.

Stephen Po-Chedley, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:

This article presents analysis from a scientific review article that uses past Earth climates as an analogue for future climate change. Although the article does not contain major inaccuracies, some of the discussion deserves more context to ensure that readers are not misled.

Mark Richardson, Research Associate, Colorado State University/NASA JPL:

An accurate and balanced article that gives readers a good flavour of the research but the reference to “Earth’s history” might confuse some when it otherwise refers to the studied period: the past 3.5 million years. Neatly explains a lot of the key points in a small word count, but I would have liked a sentence to emphasise that this reviews a lot of other work so it isn’t a shocking outlier result but is likely a reliable representation of current understanding.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

Stephen Po-Chedley, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:Collapsing polar ice caps, a green Sahara Desert, a 20-foot sea-level rise. That’s the potential future of Earth

Although background on the underlying research is provided further down, it is important to put this information into the context of the original study to give a sense of timescale and uncertainty.

The underlying study reviews the paleoclimate record and finds periods in which the Earth’s climate may serve as an analogue for the future. The authors note that the Earth, with increased atmospheric carbon dioxide and a warmer global temperatures, exhibited reductions in ice at the poles, savanna expanded into the region where the Sahara desert currently exists, and sea levels were higher. It’s important to keep in mind a few points:

- drastic changes (e.g. 20-foot sea-level rise) are expected to occur over long timescales (i.e., not in our lifetime)

- these past climate analogues don’t exactly match our current situation (Earth’s orbit, for example); so we should not expect that the past is a perfect predictor of the future

- the magnitude of these changes does depend on human actions over the next century (i.e.., how much carbon dioxide will we emit?)

Stephen Po-Chedley, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:global warming could be twice as warm as current climate models predict.

The study suggests this is an upper bound. This is important, since this seems to be a factor motivating the attention-grabbing headline.

From the study: “model-based climate projections may underestimate long-term warming in response to future radiative forcing by as much as a factor of two” and “models may underestimate observed polar amplification and global mean temperatures of past warm climate states by up to a factor of two on millennial timescales”.

This “factor of two” is also derived using model simulations of large increases of CO2 (~4x pre-industrial levels) and comparing the model simulated warming to paleoclimate data from the early Eocene climatic optimum, which was roughly 50 million years ago. During this time, the Earth’s continental configuration (land mass locations and elevation) differed from the present and these continental configuration differences were not reflected in this model/paleo-data comparison. When the authors account for this, the differences between the models and the paleoclimate record appear to be substantially reduced. This “factor of two” seems to arise in part due to an apples-to-oranges comparison.

This is slightly misleading and warrants some clarification. There is a difference between the typical warming we think of with regards to IPCC targets (i.e., 2°C by 2100), which considers the next several decades and equilibrium climate sensitivity, which will take millennia to reach and involves slow processes such as ice sheet dynamics and aspects of the carbon cycle. This study deals with the latter.

Willem Huiskamp, Postdoctoral research fellow, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:current climate predictions may underestimate long-term warming by as much as a factor of two

I would have liked the article to include, specifically, the time-scale as stated in the paper. Namely, that this is only true on millennial timescales.

Stephen Po-Chedley, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:The rate of warming is also remarkable: “The changes we see today are much faster than anything encountered in Earth’s history…”

An example of this (over the last 65 million years) is noted in this study*.

- Diffenbaugh and Field (2013) Changes in Ecologically Critical Terrestrial Climate Conditions, Science

Stephen Po-Chedley, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:This could mean the landmark Paris Climate Agreement – which seeks to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels – may not be enough to ward off catastrophe.

This paragraph is well-qualified by the author quotes in the subsequent paragraphs and the conclusion from the original study: “…we can conclude that even for a 2°C (and potentially 1.5°C) global warming – as targeted in the Paris Agreement – significant impacts on the Earth sustem are to be expected.

Stephen Po-Chedley, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:In looking at Earth’s past, scientists can predict what the future will look like

Somewhere in here, it should be noted that the past is not expected to be a perfect predictor of the future (or at least give some sense of the uncertainties involved in this research). The periods considered in the original study had important differences relative to the current Earth: different Earth-sun orbits, continental configurations, and land ice, for example. These differences affect the Earth’s climate response to greenhouse gases.

Willem Huiskamp, Postdoctoral research fellow, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:This is true, but it should be clarified that past warming events are not perfect analogues for current warming and that there is a growing body of research currently being done on the state-dependence of climate sensitivity.

Mark Richardson, Research Associate, Colorado State University/NASA JPL:Human-inflicted climate change is caused by the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas, which release heat-trapping greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane into the the atmosphere.

This is a fair statement of the scientific understanding. I applaud the author for sticking to credible scientific findings rather than opinions from bloggers or PR sheets produced by political think tanks.

Stephen Po-Chedley, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:But as the change gets larger or more persistent … it appears they underestimate climate change

This is an important point: that the potential discrepancies between models and paleoclimate data are mainly for large increases in carbon dioxide (and warming).

Stephen Po-Chedley, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:The research also revealed how large areas of the polar ice caps could collapse and significant changes to ecosystems could see the Sahara Desert become green and the edges of tropical forests turn into fire-dominated savanna.

This paragraph is more appropriately caveated (using the word “could” and “large areas” and “edges”) in comparison to the leading sentence, “collapsing polar ice caps,” which is a little less clear. A useful way to frame this information would be that: past climate have seen these profound changes and it is plausible that the future may look similar.

Mark Richardson, Research Associate, Colorado State University/NASA JPL:“we cannot comment on how far in the future these changes will occur.”

This is an important caveat. Meissner phrases it well and Rice deciding to include it was a good choice.

Mark Richardson, Research Associate, Colorado State University/NASA JPL:lead author Fischer said that without serious reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, there is “very little margin for error to meet the Paris targets.”

This is a fair summary of the necessary policy response to have a good chance of expecting we could hit the Paris targets.

It also avoids making a value judgment on the Paris Agreement and the scientists stick to technical issues.

Willem Huiskamp, Postdoctoral research fellow, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:A point that is not made often enough. Even with drastic cuts to carbon emissions, this still only gives us a moderate chance* of keeping warming under 2 degrees C.

- Raftery et al (2017) Less than 2 °C warming by 2100 unlikely, Nature Climate Change

This is a good point to make: research* indicates that there is a non-negligible chance we have already emitted sufficient greenhouse gases to commit the Earth to 1.5 degrees C of warming.

- Mauritsen and Pincus (2017) Committed warming inferred from observations, Nature Climate Change