Seven scientists analyzed the article and estimated its overall scientific credibility to be ‘high’. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Accurate, Sound reasoning.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

The article reports on the historic floods that recently occurred in Louisiana and discusses the influence of human-induced climate change on heavy-precipitation events.

Overall, the article correctly places this event in its climatic context: science clearly shows one should expect to observe more frequent intense rain events as the planet continues to warm, since it allows the atmosphere to contain more moisture. However, an increase in “flooding” severity related to global warming has not yet been clearly established.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

GUEST COMMENTS

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

Overall, the article does a good job of putting the recent heavy rainfalls in Louisiana into the broad context of climate change. While generally we expect to see more heavy downpours as the climate warms, there is a crucial caveat that’s missing- changes in the frequency of some weather systems may mean that for particular locations we wouldn’t see more extreme rainfall events. In the absence of a specific attribution study examining the role of human-induced climate change in this kind of event, we cannot say for certain that climate change increased the likelihood or intensity of these recent rains.

This detail is particularly important in places like Louisiana where extreme rainfall events can arise from different weather systems, like hurricanes for example, and there is uncertainty in how climate change is influencing some of these weather events.

Michela Biasutti, Lamont Associate Research Professor, Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University:

This piece gives a pretty standard overview of the state of the science as it pertains to extreme rainfall events and their link to climate: theoretical and model evidence (and, increasingly, observations) suggest that daily extreme precipitation will become more intense, so that high-intensity thresholds will be exceeded more often.

The piece is also careful in providing some clarification that this general trend will not necessarily be universal. One possible nuance that might be worth noting is that the link between rainfall and flooding depends heavily on landscape modification as well.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

In my view, this article does a good job reporting on the recent floods in Lousiana and, more generally, the climate-change-induced changes in the water cycle that underlie scientists’ concerns about future increase in floods. However, “heavy rainfall” is not strictly synonymous to “flooding”, and I think it could have provided more context on what is known (or not known) about current, observed changes in floods.

Ben Henley, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Melbourne:

The article is accurate. The issue of increasing precipitation extremes due to climate change is presented well. Heavy precipitation increases have been observed, and are projected to worsen with climate change. The complexities of ocean-atmosphere circulation changes due to climate change are an area of active scientific research. Increased research in this area will help us answer the public’s questions on the human fingerprint on extreme events.

Laurens Bouwer, Senior risk advisor, Deltares:

The article provides a good representation of the facts, and adds an evaluation of uncertainties, as well as pertinent quotes from experts. Various references to appropriate scientific documentation are provided as well.

Further, evidence exists attributing the increase in extreme rainfall to global warming, as summarized in the IPCC 5th report, and more importantly, there is a long line of work attributing changed likelihood of occurrence of single events -like the Louisiana flooding- to climate change (called ‘event attribution’).

Both of these topics are not mentioned explicitly, which makes the article quite careful and modest on these issues.

James Renwick, Professor, Victoria University of Wellington:

Very well-written and well-explained article, using the latest scientific understanding.

Rasmus Benestad, Senior scientist, The Norwegian Meteorological institute:

This is an important news report, however, the actual problem is somewhat under-communicated since it mixes return value analysis for a single site with occurrences taking place over many sites. The situation is more dramatic because extreme rains and flooding could happen in many places, and the likelihood for seeing such events is much higher than the probability associated with one specific site.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

The statements quoted below are from Oliver Milman; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“as surface temperatures of the oceans warm up, the immediate response is more water vapor in the atmosphere. We’re in a system inherently capable of producing more floods.”

James Renwick, Professor, Victoria University of Wellington:

Exactly. Every degree C of warming equates to around 7% more water vapor in the air. Not only does this lead to heavier rain, it adds to the warming as water vapor is a potent greenhouse gas.

“While the north-east, midwest and upper great plains have experienced a 30% increase in heavy rainfall episodes – considered once-in-every-five year downpours – parts of the west, particularly California, have been parched by drought.”

Rasmus Benestad, Senior scientist, The Norwegian Meteorological institute:

It is expected that an increased greenhouse effect will result in wet areas becoming wetter and dry regions drier because the atmospheric overturning (convection) will respond to the atmospheric opacity [1]. Overturning means air rising in some parts and sinking in others. Rising air (convection) brings moisture aloft where it cools, condenses, forms clouds, and precipitates. The descending air is dry as it is air that previously ascended and where the moisture has precipitated out during the ascent.

“The contrast in precipitation between wet and dry regions and between wet and dry seasons will increase, although there may be regional exceptions.”

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

While this picture might provide a leading order approximation, it is mostly valid over the oceans. Over land, recent research has shown that the “wet get wetter, dry get drier” picture does not really apply and things are a little more complex (e.g., see: Byrne and O’Gorman. “The Response of Precipitation Minus Evapotranspiration to Climate Warming: Why the “Wet-Get-Wetter, Dry-Get-Drier” Scaling Does Not Hold over Land” Journal of Climate (2015).)

“On Tuesday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) is set to classify the Louisiana disaster as the eighth flood considered to be a once-in-every-500-years event to have taken place in the US in little over 12 months.”

Laurens Bouwer, Senior risk advisor, Deltares:

This last sentence seems to imply that this is exceptional. However, in a country as large as the USA, it is very well possible to have multiple events each year, that exceed 100 or 500-year frequency thresholds for a particular location. Note that for this case, for multiple locations, the 500-year rainfall amount was exceeded, which is indeed exceptional.

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

As others pointed out, over a large area like the US, it is not necessarily out of the ordinary to have several places experience rare events – like record floods – in the same year. Further analysis would be required to see if the combination of these events is really unusual.

Overall, while there is an observed increase in heavy rainfall event that has been attributed to man-made global warming, changes in floods are more difficult to observe and attribute. The 2012 report on climate extremes from the IPCC indicates that “There is limited to medium evidence available to assess climate-driven observed changes in the magnitude and frequency of floods at regional scales because the available instrumental records of floods at gauge stations are limited in space and time, and because of confounding effects of changes in land use and engineering. […] Further, it points out that, so far, there is “Low confidence that anthropogenic warming has affected the magnitude or frequency of floods at a global scale.” […]

So the picture appears complex and uncertain, and while the title of this article is broadly consistent with the last quote above, caution is warranted when interpreting recent flooding events with respect to climate change.

For the US in particular, recent research indicates an increase in flooding frequency (but not necessarily magnitude) in the Northern Central US (see Mallakpour and Villarini. “The changing nature of flooding across the central United States.” Nature Climate Change (2015))

James Renwick, Professor, Victoria University of Wellington:“Noaa considers these floods extreme because, based on historical rainfall records, they should be expected to occur only once every 500 years.”

This means that such a flood is expected to have a 1 in 500 chance of happening in any given year. It does not imply that such event occurs regularly every 500 years though.

That statistic would hold if the climate were not warming. Since warming is occurring, and the amount of moisture in the air is increasing, the odds of getting these floods are getting larger/more likely.

“The National Weather Service balloon released in New Orleans on Friday showed near-record levels of atmospheric moisture, prompting the service to state: “We are in record territory.”

Emmanuel M Vincent, Research Scientist, University of California, Merced: Emmanuel Vincent, Research Scientist, Editor, Science Feedback:

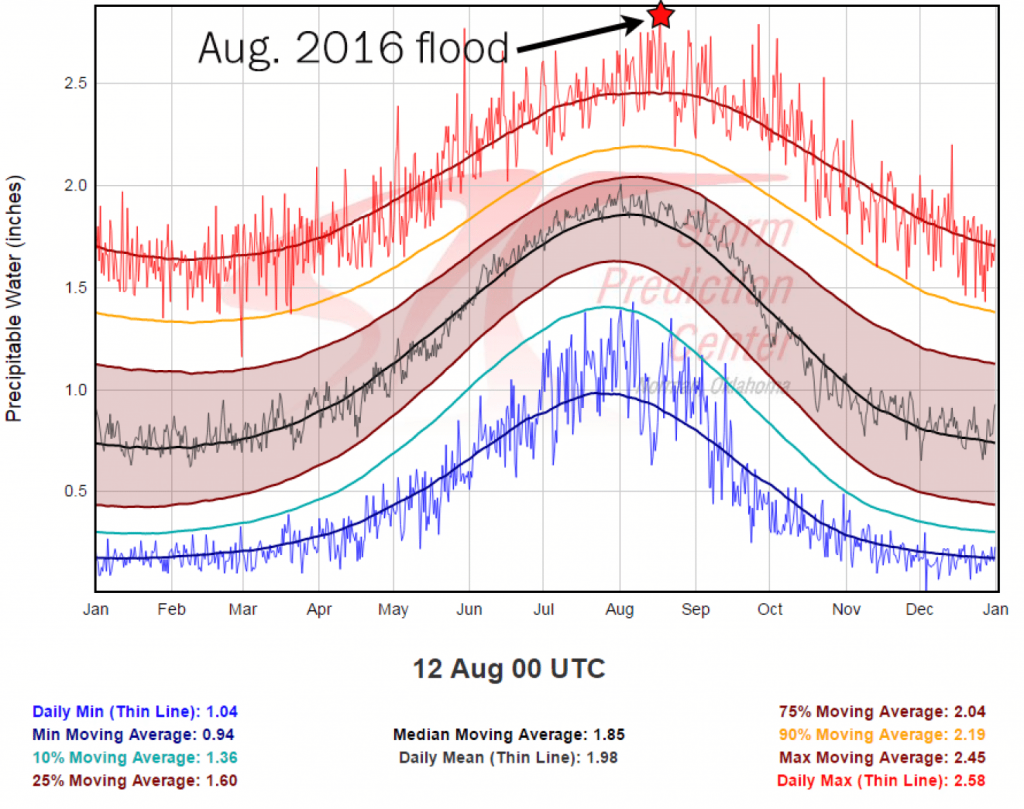

The chart below from the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center shows that the amount of ‘Precipitable Water’ in the atmosphere over southern Louisiana (Baton Rouge) was unprecedented just before the flood.

This flood fits a pattern: a recent study found that most urban flood events over the past 40 years exhibit very high amounts of precipitable water in the atmosphere.

see Schroeder et al Insights into Atmospheric Contributors to Urban Flash Flooding across the United States… (2016) Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology.

“While scientists are loathe to attribute any single event to changes in the climate, they state that warming temperatures are helping tip the scales towards altered precipitation. Some, however, bristle at the belief that because floods and storms have always occurred, they should not be linked to climate change”

Rasmus Benestad, Senior scientist, The Norwegian Meteorological institute:

It is true that floods and storms always have occurred, but they have always ocurred for a physical reason. This may be evidence suggesting that these phenomena are rather sensitive to a climate change, if modest natural changes in physical conditions already give rise to variations in the floods and storm activity. We now know that the earth’s atmosphere is changing (increased CO2 and a global warming). It would be naive to think that floods and storms do not change when important factors change while they have always changed in the past. It is also important to think about these concepts in a risk-analysis frame, and it is important to plan for various plausible scenarios.

Adam Sobel, Professor, Columbia University:

Observations over the US and many other places around the world show that heavy rain events have been becoming heavier over the last several decades. Climate models very consistently predict that this should happen as the climate warms, and basic physics leads us to interpret this change as, in large part, a consequence of increasing water vapor in the atmosphere. On this basis we can say that climate change has most likely increased the probability of an event like this. One still can’t say that climate change ’caused’ this event, as each event has many causes and no event can be viewed solely as a consequence of long-term trends.

No study can tell us that climate change caused an event like this to happen, full stop. Every weather event has many causes. Climate change is just one of them, and usually not the most immediate. At most it can push things a bit in one direction, making the weather more severe if it was going in that direction anyway. Attribution studies can describe and quantify that push. (more details in this article)