Five scientists analyzed the article and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be low to very low. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Cherry-picking, Flawed reasoning, Lack of context, Misleading.

SUMMARY

The Wall Street Journal published a range of misleading claims about Greenland’s ice melt in an op-ed by Steve Koonin, a theoretical physicist and professor at the New York University Stern School of Business. The op-ed downplays the impact climate change has on Greenland and how much it’s expected to continue to cause Greenland’s ice to melt in the future.

The Wall Street Journal op-ed asserts that it is “climate alarmism” to claim that Greenland’s ice sheet “is shrinking ever more rapidly because of human-induced climate change,” pointing out a recent headline in the Washington Post – “Greenland ice sheet on course to lose ice at fastest rate in 12,000 years” – as an example. However, scientists dispute the assertion that this finding and the Washington Post headline is exaggerated.

“There’s nothing about this statement that is incorrect or exaggerated”, Jason Briner, lead author of the study on which the headline was based, said. His 2020 study found “unprecedented mass loss from the GIS [Greenland Ice Sheet] this century, by placing contemporary and future rates of GIS mass loss within the context of the natural variability over the past 12,000 years.”[1] While Koonin notes in his op-ed that “climate unfolds over decades,” and thus smaller timescales shouldn’t be used to determine climatic changes, Briner emphasizes that his study modeled rates of ice loss per century.

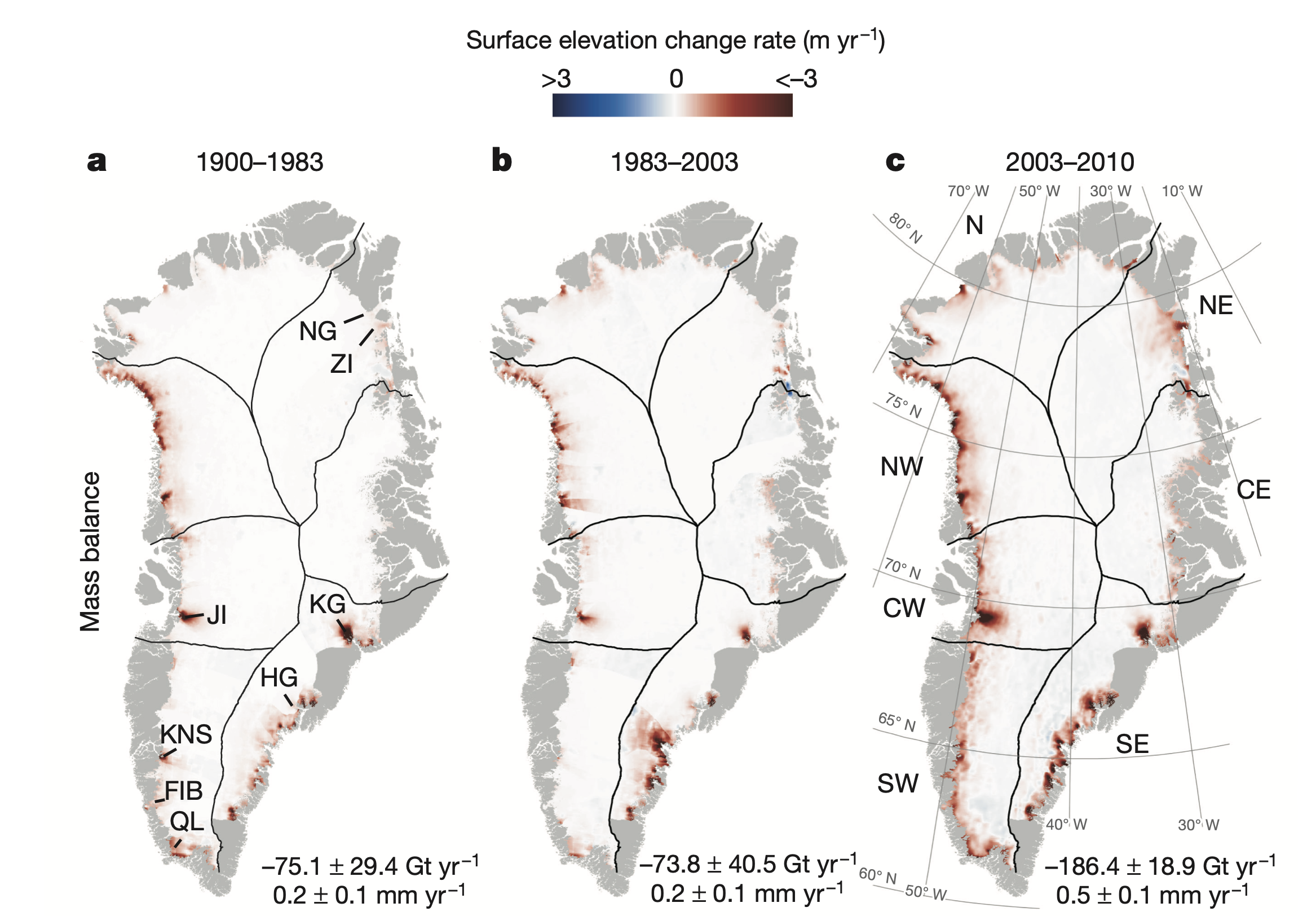

Koonin claims that the idea that human-caused climate change is to blame for Greenland’s melt is “simplistic” and that “the annual loss of ice has been decreasing in the past decade even as the globe continues to warm.” Greenland’s ice melt is impacted by more than just climate change, and scientists are still working to better understand how both natural forcings and human-caused climate change affects Greenland’s ice melt. However, a 2019 study by IMBIE, an international collaboration of polar scientists, found that just over half of ice losses between 1992 and 2017 are a result of reduced SMB [surface mass balance] (mostly meltwater runoff) associated with changing atmospheric conditions”, and that the “rate of ice loss has generally increased over time” since the early 1990s.[4] Though Koonin claims that Greenland’s ice loss “is no larger today than it was in the 1930s,” Kjeldsen et al found that ice loss between 2003 and 2010 “not only more than doubled relative to the 1983–2003 period, but also relative to the net mass loss rate throughout the twentieth century.”[5]

Figure 1 — Surface elevation change rates in Greenland during 1900-1983 (a), 1983-2003 (b), and 2003-2010 (c). The numbers listed below each panel are the integrated Greenland-wide mass balance estimates expressed as gigatonnes per year and as millimetre per year GMSL (global mean sea level) equivalents. From Kjeldsen et al. 2015[3].

Human-caused climate change is already accelerating Greenland’s melting and is predicted to continue to accelerate it in the future[1]. In addition to Greenland, most glaciers around the planet are also melting at an accelerating pace[6]. This melt, in addition to the expansion of the ocean as it warms, contributes to sea level rise, which research has shown has accelerated in the last few decades.[9]

As Twila Moon, research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, explained in a 2021 Climate Feedback review of another set of misleading claims made by Koonin, Greenland’s average per year ice loss during 2003-2010 was roughly 2.5 times higher than during 1900-2003. In 2018, Trusel et. al examined observed and modeled ice melt rates in Greenland over the last 350 years, finding:[2]

“Today, surface melting and melt-induced runoff in Greenland occur at magnitudes not previously experienced over at least the last several centuries, if not millennia. Melt–temperature nonlinearity and general circulation changes mean that further twenty-first-century warming has important implications for the ice-sheet mass balance, by accelerating the intensity of surface melting and amplifying [Greenland Ice Sheet] GrIS contributions to global sea-level rise.”

Koonin also makes claims about sea level rise in the op-ed, stating that, in a likely emissions scenario, ice melt from Greenland causes sea level to rise by 3 inches by the end of the century. This is supported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (which Koonin cites), which stated in 2013: “Based primarily on Nick et al. (2013), we assess the upper limit of the likely range of this dynamical effect to be 85 mm for RCP8.5 and 63 mm for all other RCP scenarios for the year 2100.”[7] A 2019 study, however, concluded that the contribution could be greater: 5 to 33 cm [1.9-12.99 inches] to sea level by 2100.[8] And Briner notes that figure leaves out critical context about sea level rise from other sources: Antarctica, mountain glaciers, and thermal expansion of the ocean, for instance.

“While the article uses real data on ice mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet, the message of slower rate of ice mass loss in the past 8-9 years does not mean that human-induced warming is not a concern, or less of a concern now,” said Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Virginia. “Overall, the article is, I believe, intentionally misleading and flawed, by presenting real data to support inaccurate interpretations and potential outcomes.”

UPDATE (28 Feb. 2022): On 27 February 2022, seven scientists, including Marco Tedesco, published a response to Koonin’s article in the Wall Street Journal. Koonin’s argument, the scientists write, is “based on an incorrect interpretation of the plotted data, which comes from research by one of us, Mr. Mankoff.

Mr. Koonin claims that ‘the annual loss of ice has been decreasing in the past decade even as the globe continues to warm.’ While that is factually correct, it is an invalid interpretation, considering only the last decade and excluding previous periods. This is often referred to as ‘cherry picking.’”

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:

While the article uses real data on ice mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet, the message of slower rate of ice mass loss in the past 8-9 years does not mean that human-induced warming is not a concern, or less of a concern now. The slower rates of ice mass loss highlight the dynamic, non-linear, and often asynchronous response of the ice sheet to short (annual and sub-annual) changes in weather; yet the long-term, multi-decadal trends in climate and ice mass loss are where we should focus our attention. Overall, the article is, I believe, intentionally misleading and flawed, by presenting real data to support inaccurate interpretations and potential outcomes.

Marco Tedesco, Lamont Research Professor, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University:

The article picks only the last 10 years, excluding the remaining time series for the context, hence “cherry-picking” that period and not considering many climatic factors when describing the downward trend.

Eric Rignot, Professor, University of California Irvine & Jet Propulsion Laboratory:

The article does not quote clear sources and time periods for mass loss, which is increasing with time. Quoted numbers, 110gt/yr, is low and obscure.

The article does not discuss the linkage between physical processes driving the mass loss and human activities, hence has little logic and physical basis for making claims.

The article’s claims exaggerate the statements made by scientists about the urgency of the situation but the argument is vague, not quantitative and hand wavy.

The old argument that the 30s were warmer than present is false.

Anders Anker Bjork, Assistant professor, University of Copenhagen:

Science knows what caused the early 20th century warming and what is causing the current warming. The WSJ title could just as well have been: ‘Last decade showed highest mass loss from Greenland ever measured’.

ANNOTATIONS

“The average annual ice loss … would cause sea level to rise by 3 inches by the end of this century,

Jason Briner, Professor, Department of Geology, University at Buffalo:

Of course keep this 3” in perspective. This does not include sea level coming from Antartica, from mountain glaciers, from thermal expansion of the oceans. It is a little narrow (and sure, maybe underwhelming for some) to consider just one of these sources in isolation.

“and if losses were to continue at that rate, it would take about 10,000 years for all the ice to disappear, causing sea level to rise more than 20 feet”

Jason Briner, Professor, Department of Geology, University at Buffalo:

This is only true if the rate of annual ice loss were to remain the same as today’s rate for a long time. That said, highly vetted and peer-reviewed climate and ice sheet models, which are very good at correctly modeling Earth’s past, suggest that the present rates of ice sheet mass loss will not stay the same, but will increase.[1]

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:

Rather than extrapolating cumulative ice loss, a peer-reviewed study that uses fine-scale ice sheet model with uncertainty quantification indicates the Greenland Ice Sheet could disappear entirely in 1,000 years.[8]

The “notion that humans are melting Greenland” is “simplistic”, “There are large swings in the annual ice loss and it is no larger today than it was in the 1930s, when human influences were much smaller”, “the annual loss of ice has been decreasing in the past decade even as the globe continues to warm.”

Jason Briner, Professor, Department of Geology, University at Buffalo:

Of course such a statement is simplistic, yet still likely more or less true. And of course there are large swings in the annual ice loss rate – these swings have tracked well both Arctic climate (on decadal scales) and with modes of climate variability and weather patterns (on the sub-decadal scale).

Annual loss has been decreasing in the past decade

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:

The rate of ice mass loss has decreased since 2013, yet the annual loss of ice is still considerable and reflects the long-term impact of atmospheric warming and ice dynamic response to such.[4]

[The WSJ article also criticizes the following statement made by, according to Koonin, “the media and politicians”:]

“Greenland ice sheet on course to lose ice at fastest rate in 12,000 years.”

Jason Briner, Professor, Department of Geology, University at Buffalo:

Of course this hits home, as the author of the paper with more or less that title. There’s nothing about this statement that is incorrect or exaggerated. It is important to know that it is based on a study that compiled and modeled rates of mass loss PER CENTURY and relies on the well-vetted models mentioned above to provide best estimates (with ranges given uncertainties) for this century (which isn’t over yet!). Our model, which performed well in simulating Greenland’s history, and stacks up well against other models that took part in a state-of-the-art model comparison effort, suggests that rates this century will, on average, have higher mass loss rates than at present as the Arctic is expected to heat up.

It is all this information that goes into that quote.

Its shrinking has been a major cause of recent sea-level rise, but as is often the case in climate science, the data tell quite a different story from the media coverage and the political laments

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:

The data reflect major losses of ice, via ice thinning, ice mass loss, and accelerated ice discharge, despite a lower magnitude of overall ice mass loss since 2013; but the mass balance is still negative and on track (based on the multi-decadal trend) to continue to lose mass.

Since human warming influences on the climate have grown steadily—they are now 10 times what they were in 1900— you might expect Greenland to lose more ice each year. Instead there are large swings in the annual ice loss and it is no larger today than it was in the 1930s, when human influences were much smaller.

Lauren Simkins, Assistant Professor, University of Virginia:

This is a really simplistic interpretation that negates physics of glacial ice and its response to annual ocean and atmospheric temperatures. The non-linear response of the Greenland Ice Sheet to warming and the lag time between, for example, a warm month or couple of months and ice mass loss means that there are asynchronous changes in climate and ice mass balance.

REFERENCES

- [1] Briner et al. (2020). Rate of mass loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet will exceed Holocene values this century. Nature.

- [2] Trusel et al (2018) Nonlinear rise in Greenland runoff in response to post-industrial Arctic warming. Nature.

- [3] 1 – Kjeldsen et al. (2015) Spatial and temporal distribution of mass loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet since AD 1900. Nature.

- [4] The IMBIE Team (2019). Mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2018. Nature.

- [5] Kjeldsen et al. (2015). Spatial and temporal distribution of mass loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet since AD 1900. Nature.

- [6] Hugonnet et al (2021). Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature.

- [7] Church et al. (2013). Sea Level Change. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- [8] Aschwanden et al. (2019). Contribution of the Greenland Ice Sheet to sea level over the next millennium. Science advances.

- [9] Nerem et al. (2018) Climate-change–driven accelerated sea-level rise detected in the altimeter era. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.