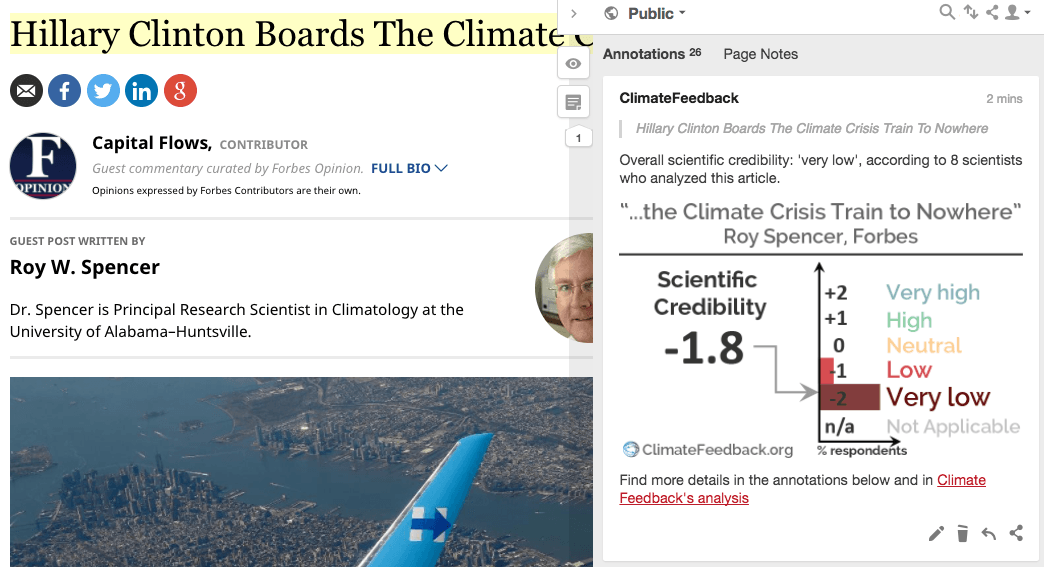

Eight scientists analyzed the article and estimated its overall scientific credibility to be ‘very low’. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Biased, Inaccurate, Misleading.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This commentary by Dr. Roy Spencer published in the opinion section of Forbes makes a number of inaccurate and misleading scientific claims. For instance the article claims that climate change would be so slow that “it cannot be observed by anyone in their lifetime”, which is demonstrably wrong. It also misrepresents the impacts of climate change and makes claims about sea level and temperature records that are not supported by the evidence.

Note: This article was evaluated only for scientific accuracy—Climate Feedback does not endorse or oppose political opinions.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

If the link does not work due to the landing page ads on Forbes, install the Hypothesis extension in your browser and switch it on from the article page.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Kerry Emanuel, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, MIT:

The article is inaccurate in several places and conveys that one must choose between solving immediate problems, such as poverty, and long-term risks such as climate change. We can do both, and indeed must do both if we take poverty seriously, since climate change disproportionately affects the poor.

Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor, First Street:

The author makes a number of statements that are not supported by the science or by established scientific process. He is basically playing by a different set of rules than the scientific community at large, which allows him to say anything he wants in order to make his case. A number of statements are misleading and some are obfuscating, particularly in terms of potential impacts of climate change on humans.

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

This article by Roy Spencer is misleading when it comes to his own work on tropospheric temperature changes and several times severely wrong outside of his expertise. It does not give a fair overview of the state of the science.

Peter Gleick, President Emeritus and Chief Scientist, Pacific Institute:

Almost every claim in this article is scientifically inaccurate or misleading.

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

This articles uses a number of misleading statements, logical flaws and unsubstantiated claims to try to defend the erroneous idea that climate change is nothing to worry about, that there is nothing to do about it anyway, and that wanting to address it is all a power play by politicians.

Benjamin Horton, Professor, Earth Observatory of Singapore:

The discussion on sea level rise is misleading.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

The statements quoted below are from Roy Spencer; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Global warming and climate change, even if it is 100% caused by humans, is so slow that it cannot be observed by anyone in their lifetime. Hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, droughts and other natural disasters have yet to show any obvious long-term change.”

Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor, First Street:

This statement is far too broad to be supportable, and is misleading in a few ways. Among the many aspects and impacts of climate change, some are evolving slowly and others more quickly (quickly enough to be detected within a 70-year human lifetime). There is a very important difference between saying “there has been no change”, versus “the data records are not long enough to formally detect a change”. For example, our present records of hurricanes do in fact show very large and statistically significant increasing trends in a number of measures since the 1800s. But we also know that the older data are of a lower quality than modern data, so we are uncertain of what part of the trends are due to the data issues and what part may be due to human influences.

The scientific community has established a very strict set of rules for formally establishing whether or not a trend has been detected, and we constrain our statements within this rigid framework. The author’s statement here violates those rules and is unsupportable

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

As others have noted, this is flat out wrong. With barely 1C of global warming there are already changes in temperatures, humidity precipitation patterns, sea ice, land ice, sea level, vegetation, etc., that i) can be observed, and ii) can be attributed to human-made global warming. And certainly in the coming decades, that is, within our “lifetime”, further changes are going to be even more obvious.

“Furthermore, the overall increases in such things as hurricanes and tornadoes have not materialized.”

Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor, First Street:

Again, this statement is not supported by the science. We are seeing changes. We just don’t have long enough data records to formally detect the changes and attribute them to human influence. The rules of detection and attribution are well established, strict, and conservative. The author’s statement here is outside of the rules and can’t be supported in any true formal scientific sense. […] It’s wrong and unsupportable to say that there have been no changes. Our theory of hurricanes and our best numerical models inform us that hurricanes will become stronger as the world warms, and that the increase will be most evident in the strongest hurricanes. These are the hurricanes that kill the most people and do the most damage.

Furthermore, increases in strength or number are not the only ways that hurricanes can change. There is mounting evidence that tropical cyclones in various regions of the world are migrating poleward. This creates significant changes in hazard exposure and human mortality risk, even in the absence of any changes in strength.

“Drought in the western U.S. pales in comparison to the mega-droughts tree rings tell us existed in centuries past.”

Peter Gleick, President Emeritus and Chief Scientist, Pacific Institute:

There are many scientific papers, going back years now, that show the influence of climate changes on the western US droughts. The fact that there have been “mega-droughts” in the past is irrelevant to whether climate changes are now influencing current droughts.

See:

- Swain et al. (2014) The Extraordinary California drought of 2013/2014: Character, Context, and the role of climate change, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

- Mann and Gleick (2015) Climate change and California drought in the 21st century, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

In Swain et al. (2014)*, we do find that global warming has increased the likelihood of one of the “ingredients” of the California drought—specifically, very high middle atmospheric pressures. A more direct reference might be Diffenbaugh et al. (2015)*, where we specifically quantify the degree to which human caused warming has increased the likelihood of drought in California. There are other papers, as well, that find at least a fractional contribution of warming to this event.

I also agree with Peter Gleick’s remark that the existence of past droughts of large magnitude is largely irrelevant when seeking causes of the present one, and does not disprove a human role in modern droughts.

- Swain et al. (2014) The Extraordinary California Drought of 2013/2014: Character, Context, and the Role of Climate Change, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

- Diffenbaugh et al. (2015) Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

Note the comparing reconstructions of past droughts with climate model projections suggests that “future drought risk will likely exceed even the driest centuries of the Medieval Climate Anomaly (1100–1300 CE) in both moderate (RCP 4.5) and high (RCP 8.5) future emissions scenarios, leading to unprecedented drought conditions during the last millennium”.

- See Cook et al. (2015) Unprecedented 21st century drought risk in the American Southwest and Central Plains, Sciences Advances.

“Lake-bottom sediments in Florida tell us that recent major hurricane activity in the Gulf of Mexico has been less frequent than in centuries past.”

Kerry Emanuel, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, MIT:

The lake-bottom sediment study, in which I participated, catalogued hurricanes at a particular location over several thousand years. There are indeed centennial-scale variations at particular locations that are not strongly correlated across different locations, so the authors interpreted these fluctuations in terms of changing [hurricane] tracks. The technique cannot distinguish between a weak event nearby and a strong one at a distance, so there is little data pertaining to storm intensity.

“ It has now, even after Hurricane Matthew, been over 4,000 days since a major hurricane (Category 3 or stronger) has made landfall in the U.S. ”

Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor, First Street:

The definition of US major hurricane landfall is strict but also arbitrary, and isn’t a particularly good measure of coastal risk. The threshold of a major hurricane, and the restriction that the center of a hurricane must move over land is somewhat ad hoc and may obfuscate the points of relevance. For example, many coastal communities have experienced major hurricane landfalls over the past 4,000 days. They just don’t happen to be within the geopolitical border of the contiguous US. Matthew is in fact a good example for why the author’s statement is misleading. Matthew did a great deal of damage as a major hurricane without technically having its center touch land. The fact that it didn’t make formal landfall as a major hurricane is not particularly relevant when considering coastal hazard exposure and human mortality risk.

Kerry Emanuel, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, MIT:

One can always cherry-pick a sufficiently narrow statistic, like major landfalling continental US hurricane, that will support one’s prejudice. The fact is that there has been no pause in ALL Atlantic basin or landfalling (including regions outside the US) storms.

“Sea level rise, which was occurring long before humans could be blamed, has not accelerated and still amounts to only 1 inch every ten years. If a major hurricane is approaching with a predicted storm surge of 10-14 feet, are you really going to worry about a sea level rise of 1 inch per decade?”

Benjamin Horton, Professor, Earth Observatory of Singapore:

Proxy analysis has clearly shown an acceleration in rate of sea-level rise. Our research* found that the rate of sea-level rise on the US Atlantic coast is greater now than at any time in the past 2,000 years. The research also shows a consistent link between global mean surface temperature and changes in sea level for the past millennium. The study shows that after relatively subtle changes in temperature and sea-level rise over the last 2,000 years, the rate of sea-level rise increased in the late 19th century.

Sea-level rise contributes significantly to the frequency of flooding from hurricanes. The contribution from sea-level rise to flood height works in together with other factors such as timing of the storm relative to high tide, and the strength and direction of individual hurricanes. Sea-level rise between hurricanes raises the “baseline” water level and makes flooding more likely. We published another paper* showing that New York City can expect nine-foot floods, as intense as that produced by 2012’s Superstorm Sandy, at least four times more frequently over the next century. We report that floods as intense as Sandy’s would have occurred about once every 400 years on average under present day sea-level rise conditions, but that over the 21st century are expected to be about four times more probable (once every 100 years) due to an acceleration in the rate of sea-level rise.

- Kemp et al. (2011) Climate related sea-level variations over the past two millennia, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Lin et al. (2016) Hurricane Sandy’s flood frequency increasing from year 1800 to 2100, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Peter Gleick, President Emeritus and Chief Scientist, Pacific Institute:

A major storm that has a sea-level higher than it would otherwise have been without climate change will simply be more damaging. It doesn’t matter that current sea-level rise changes are slow. Sandy’s storm surge hit at high tide—a tide that was higher than it would otherwise have been because of human-caused climate change. Some estimates are that damages were many billions of dollars higher as a result.

Kerry Emanuel, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, MIT:

Sea level rise is indeed accelerating and is currently tracking predictions that are consistent with a roughly 1 meter (3 foot) rise by the end of the century. We are already seeing bad effects in places like Miami Beach. And 1 meter makes a large difference, so if one is concerned about one’s descendants, then yes, it is something to worry about.

Jim Kossin, Distinguished Science Advisor, First Street:

Sea level rise and its impacts vary considerably by region. To state a global mean number is misleading and irrelevant to those regions that are most vulnerable. With or without hurricanes added to the mix, the impacts on humans from sea level rise can be seen now. The author’s comparison of hurricane storm surge to sea level rise is very misleading and blurs the relevance of sea level rise to humans. Sea level rise is creating nuisance flooding in a number of places. The fact that hurricane storm surge is bigger is irrelevant and does not change the fact that people are being impacted.

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

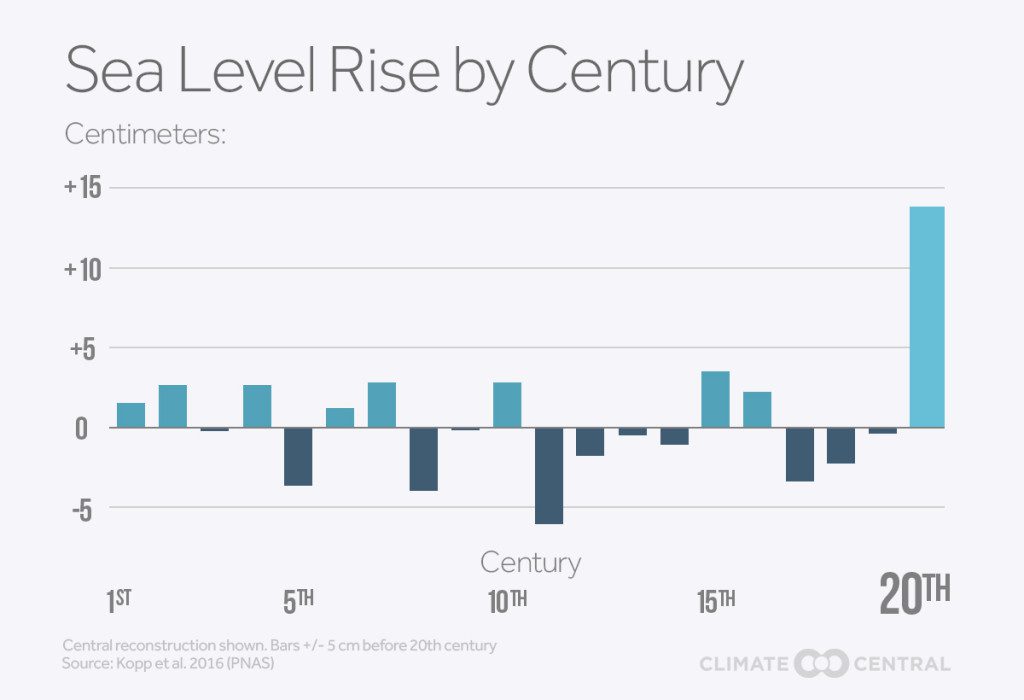

Sea level rise started before we had good instrumental observations, which makes it harder to see the acceleration. If you look sea level rise for longer periods based on indirect (proxy) evidence, it is clear that the current sea level rise is much faster than it was during the last 1000 years.

See for example this article on RealClimate on a recent study for the last 2000 years.

It will depend on our actions whether sea level rise will accelerate much more. See this article on the expected sea level rise for the coming century.

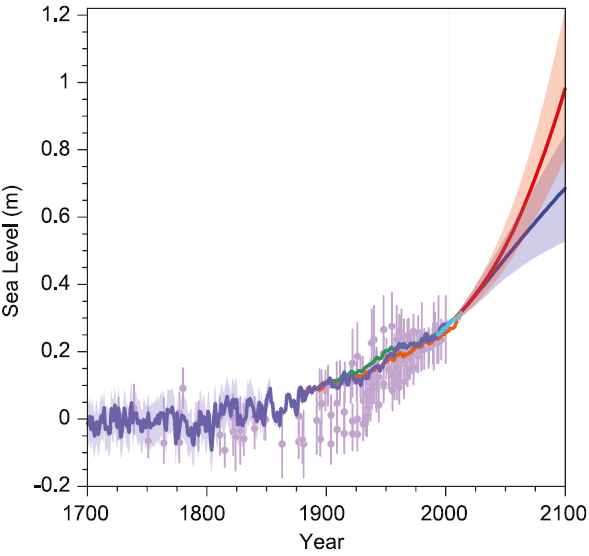

Figure – Past and future sea-level rise. For the past, proxy data are shown in light purple and tide gauge data in blue. For the future, the IPCC projections for very high emissions (red, RCP8.5 scenario) and very low emissions (blue, RCP2.6 scenario) are shown. Source: IPCC AR5 Fig. 13.27

“If Hillary would have fact-checked her example of sea level rise in Norfolk, Virginia, she would have found out that the experts already know this is mostly due to the land there sinking.”

Benjamin Horton, Professor, Earth Observatory of Singapore:

Without global warming, global sea level would have risen by less than half the observed 20th century increase and might even have fallen. We published another paper in PNAS (Kopp et al., 2016*) that showed that with global warming global sea level rose by about 14 centimeters, or 5.5 inches, from 1900 to 2000. That is a substantial increase, especially for vulnerable, low-lying coastal areas. The sinking of land in Virginia is responsible for the slow sea-level rise from 3000 years ago to the beginning of the industrial revolution. The 20th century rise was extraordinary in the context of the last three millennia—and the rise over the last two decades has been even faster. The study’s global sea-level reconstruction calculated how temperatures relate to the rate of sea-level change. Based on this relationship, the study found that, without global warming, 20th century global sea-level change would very likely have been between a decrease of 3 centimeters (1.2 inches) and a rise of 7 centimeters (2.8 inches). A companion report finds that, without the global warming-induced component of sea-level rise, more than half of the 8,000 coastal nuisance floods observed at studied US tide gauge sites since 1950 would not have occurred.

- Kopp et al. (2016) Temperature-driven global sea-level variability in the Common Era, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

“[…]even if the countries of the world agree to do what they promised on climate change, […]the promised actions will have no measurable effect on future global temperatures.”

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

The current promises of governments around the world (INDCs) are not enough to stay below a warming of 2 °C, but they do make a difference. In an article in Nature this June, Joeri Rogelj and colleagues: “The INDCs collectively lower greenhouse gas emissions compared to where current policies stand, but still imply a median warming of 2.6–3.1 degrees Celsius by 2100.”

“[…]until we develop a practical, cost-competitive alternative to fossil fuels, it is unlikely that renewable energy will ever make up more than 15-20% of global energy requirements.”

Celine Guivarch, Senior researcher, CIRED, Ecole des Ponts:

In many countries renewables are already competitive compared to fossil fuels, and represent a larger share than the 15-20% mentioned here. Costs of renewable are still falling. And the investment in renewable is accelerating. For instance, the IEA has revised its renewable forecasts upwards. Many scenarios and studies foresee that renewables could represent a much larger share than 15-20%.

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:

Dr. Spencer provides no evidence to back up his assertion that renewables are necessarily limited to 15%-20% of generation. Prices of renewable technologies have been falling rapidly over the past decade, with solar power alone falling 60% and wind falling 40%. In more and more parts of the world renewables are cost-competitive with traditional fossil fuels. And unlike traditional fuels, renewables are not mature technologies and likely have additional price reductions to come.

In some areas additional storage might be needed to balance out high renewable penetration. Even here storage costs have fallen dramatically due to advances in battery technologies. Additionally, electric vehicles and natural gas both enable additional renewables through grid balancing.

“And since the biggest risk to humanity is poverty, if we allow policymakers to have their way, the resulting energy poverty will indeed cause the deaths of some of our children and grandchildren.”

Celine Guivarch, Senior researcher, CIRED, Ecole des Ponts:

Poverty and energy poverty are indeed a risk for humanity; but current understanding shows that unmitigated climate change would hinder the efforts of poverty alleviation, because climate change impacts bear on most vulnerable countries and people.

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:

There is no necessary tradeoff between fighting poverty and climate change. There are actually a number of co-benefits to a more sustainable development pathway. For example, outdoor air pollution driven largely by coal use currently kills well over a million people annually*, and represents one of the most urgent public health crises on the planet. Addressing it by transitioning from coal to renewables, nuclear, and natural gas could benefit both health and the environment in developing countries.

- Rohde (2015) Air Pollution in China: Mapping of Concentrations and Sources, PLOS ONE

“But the observed warming as monitored by satellites (our only truly global monitoring system) has been only about half of what computerized climate models say should be happening.”

Carl Mears, Senior Research Scientist, Remote Sensing Systems (RSS):

The statement is fairly accurate but leaves the inference of causes up to the reader. A recent paper by Santer et al. (2016)* investigated this issue in considerable detail. For middle tropospheric temperatures the paper found that, on average, models showed 1.71 times more warming than the mean of the most recent version of the satellite data for the 1979-2015 period. This is for near global mean temperatures. For the lower troposphere, the models show about 2 times more warming than the satellites. Note that the Remote Sensing Systems lower tropospheric dataset has not yet been upgraded to the latest version, which is likely to show more warming.

The article does not discuss possible reasons for this discrepancy, but given the tone of the rest of the article, the reader is expected to use the trend differences as evidence that long-term projections by climate models are suspect. These ratios do not provide such evidence. At least part of the discrepancy is known to be caused by errors in the forcings used to drive the CMIP-5 climate models. After the year 2000, the CMIP-5 models were driven by forecast values for important parameters such as volcanic aerosols, solar output, and stratospheric ozone. The forecasts turned out to be slightly inaccurate, causing the models to predict more warming than they would have if the correct forcings had been used. (Of course, these correct forcings were in the future and thus unknowable at the time the model computations were performed). Other possible causes include natural variability in the real world (which might produce a period of reduced warming) and errors in the model physics. Only errors in the model physics would cause long-term global warming to be overestimated, and there is no significant evidence that supports large errors in the model physics. Over a much longer time period, 1880-present, the warming at the surface agrees well with that expected by the CMIP-5 models. The longer time period is important because the effects of random fluctuations due to natural variability tend to average away as the time period considered gets longer.

- Santer et al. (2016) Comparing tropospheric warming In climate models and satellite data, Journal of Climate