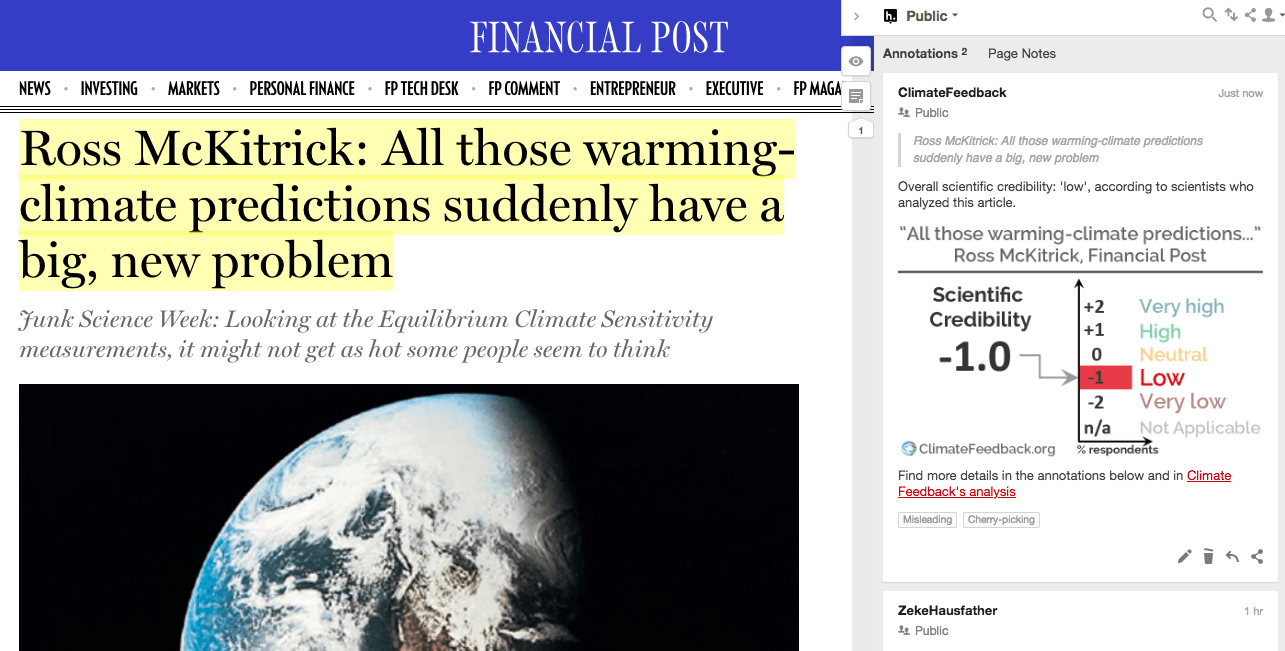

Five scientists analyzed the article and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be 'low'. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Cherry-picking, Misleading.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This opinion published by the Financial Post, written by economist Ross McKitrick, claims that Earth’s climate is much less sensitive to additions of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide than climate scientists think. The article further claims that global warming is, therefore, not an important problem—and may even be beneficial.

Scientists who reviewed the article found that this argument is misleading, and relies on ignoring all but a select few of the many studies that exist on this topic. These studies use a particular method for estimating this “equilibrium climate sensitivity” that other research has shown to be problematic. An informed opinion should consider all the scientific lines of evidence available instead of picking the ones that agree with the author’s predetermined conclusion. Taken together, that evidence does not support the article’s argument.

For a detailed summary of what we know about Earth’s equilibrium climate sensitivity, see this article at Carbon Brief.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Reto Knutti, Professor, ETH Zürich:

This is an opinion piece in the “lukewarm” category, arguing that climate models are wrong, future warming will be small, based on carefully selected publications, misleading presentation, and incorrect reporting of the underlying data.

This opinion piece is a completely one-sided and misleading representation of what we know about the long-term response of temperature to greenhouses gases.

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:

This article selectively cherry-picks studies showing low climate sensitivity, leaving out whole lines of evidence (e.g. paleoclimate studies) that agree with the sensitivity estimates found in models. It also glosses over the many criticisms of instrumentally based (or “energy balance”) sensitivity estimates published in recent years.

Patrick Brown, Assistant Professor, San Jose State University:

The article makes a big deal about the fact that some methods of estimating equilibrium climate sensitivity tend to give smaller results than others. This is not a new finding and it is not under appreciated in the climate science literature or by the IPCC. The methods for estimating climate sensitivity discussed in the article are already incorporated into the uncertainty ranges of climate sensitivity considered by the IPCC and other assessments. Overall, it is best practice to consider results from a full range of methods and to not focus on the single method that produces the lowest estimate of climate sensitivity.

Mark Zelinka, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:

Rather than present the Lewis and Curry (2018) study in the context of the multitude of other estimates of equilibrium climate sensitivity, the article shows only results from studies using similar approaches that confirm the claim in the title. Such energy budget approaches consistently underestimate climate sensitivity primarily because they rely on a conceptual model of forcing and response that is too simple for the problem at hand, as an explosion of recent literature on the topic has shown. This body of evidence is either dismissed out of hand or ignored entirely in the article.

Andrew Dessler, Professor, Texas A&M University:

This paper misrepresents that state of science. It selectively quotes analyses that support the author’s opinion, while ignoring all contrary evidence. Putting all of the evidence together, there’s no reason to think that climate models are wrong.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

Patrick Brown, Assistant Professor, San Jose State University:People who study the impacts of global warming have found that if ECS is low — say, less than two — then the impacts of global warming on the economy will be mostly small and, in many places, mildly beneficial. If it is very low, for instance around one, it means greenhouse gas emissions are simply not worth doing anything about.

This passage is misleading. It seems to imply that society has already decided to exactly double CO2 concentrations and has committed to emitting no further greenhouse gasses after that. If that were the case, then we could in fact assess climate change impacts in the manner done here.

However, society is far from committing to stabilizing CO2 concentrations at “only” twice their preindustrial levels. We may go well beyond that. In that case, lower equilibrium climate sensitivity just means that it takes longer to reach a given level of warming. So even if climate sensitivity turns out to be very low, all the worst impacts could still be realized—they would just be delayed.

Patrick Brown, Assistant Professor, San Jose State University:We may not be able to stop it, but we’d better get ready to adapt to it.

The magnitude of equilibrium climate sensitivity has nothing to do with whether or not we can stop climate change. Global temperatures will stabilize when the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gasses stabilize. So regardless of the climate sensitivity value, we can “stop” climate change by stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations.

Their ECS estimate is 1.5 degrees, with a probability range between 1.05 and 2.45 degrees.

Reto Knutti, Professor, ETH Zürich:

The opinion piece claims that Lewis and Curry account for changes in feedback and incomplete observational coverage, yet quotes the range that does not! The range that does include those effects has a median of 1.76 K (5−95%: 1.2−3.1 K). Whether this is deliberate or an oversight is hard to know, but it certainly does not add to the credibility of the piece.

But it is part of a long list of studies from independent teams (as this interactive graphic shows), using a variety of methods that take account of critical challenges, all of which conclude that climate models exhibit too much sensitivity to greenhouse gases.

Andrew Dessler, Professor, Texas A&M University:

While several groups have indeed done this calculation, and they all get the same answer, these groups are basically doing versions of the same calculation with the same data. Thus, their agreement means much, much less than is suggested here. If there is a problem with the methodology, which several recently published papers have suggested, then all of them are wrong.

Reto Knutti, Professor, ETH Zürich:

The text refers to a “long list of studies from independent teams“ using “a variety of methods”, but effectively they are all doing the same thing: relating forcing and ocean heat uptake to the observed warming. Dozens of other studies have demonstrated that the simple energy balance models provide climate sensitivity estimates that are too low1,2. The study by Lewis and Curry claims to account for that, but the effects could be much bigger3.

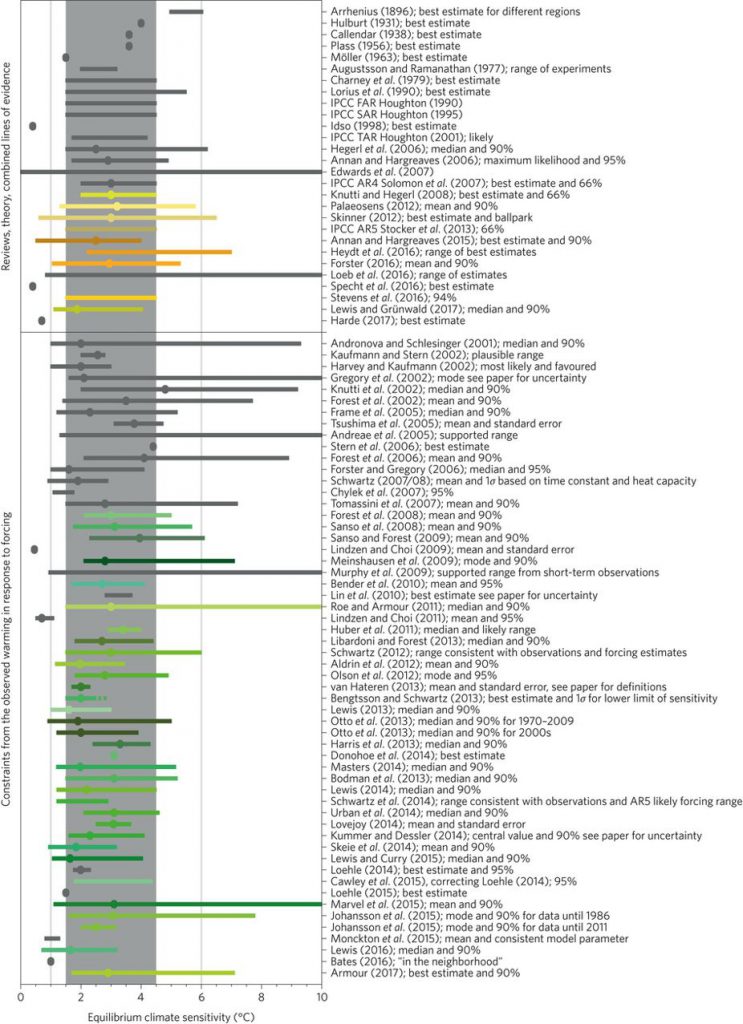

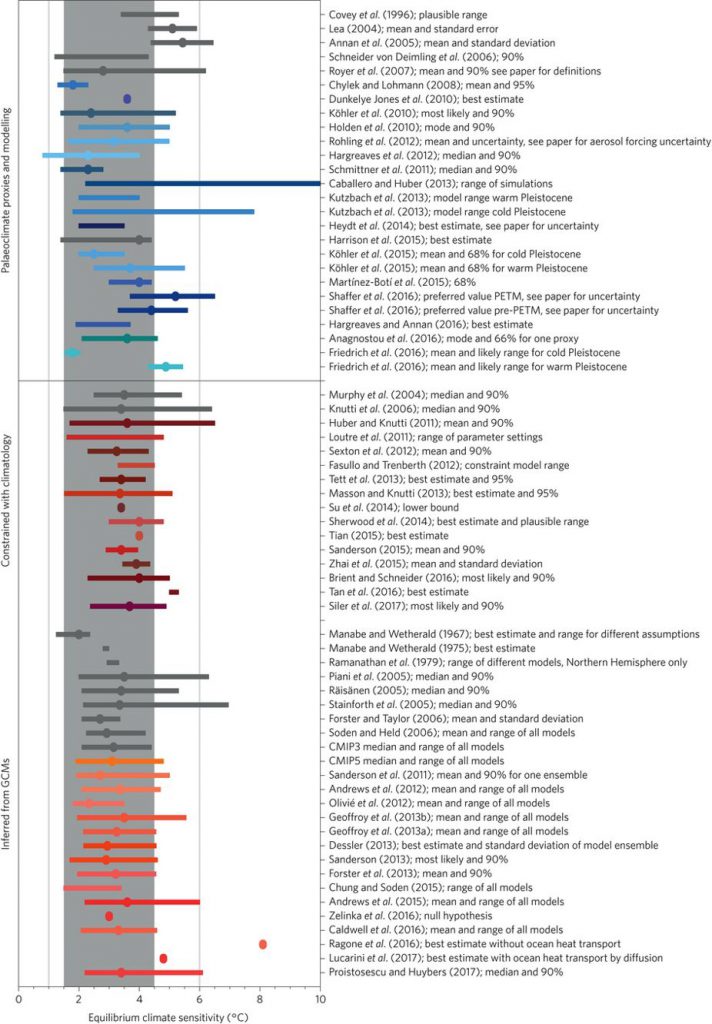

The text fails to discuss that there are literally hundreds of studies about climate sensitivity. We refer to over 400 in our review2. Taken together, they do show a substantial uncertainty range, but they do not support the “lukewarm” position. And there is no evidence that estimates of climate sensitivity have decreased recently.

- 1-Knutti and Rugenstein (2015) Feedbacks, climate sensitivity and the limits of linear models, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, A

- 2-Knutti et al (2017) Beyond equilibrium climate sensitivity, Nature Geoscience

- 3-Gregory and Andrews (2016) Variation in climate sensitivity and feedback parameters during the historical period, Geophysical Research Letters

Cherry pick much? For a better perspective, refer to the recent comprehensive literature review by Knutti et al*, which shows ECS estimates from a wide range of methodologies (see figures below). Notably, energy budget estimates are consistently biased low relative to other lines of evidence.

- Knutti et al (2017) Beyond equilibrium climate sensitivity, Nature Geoscience

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:

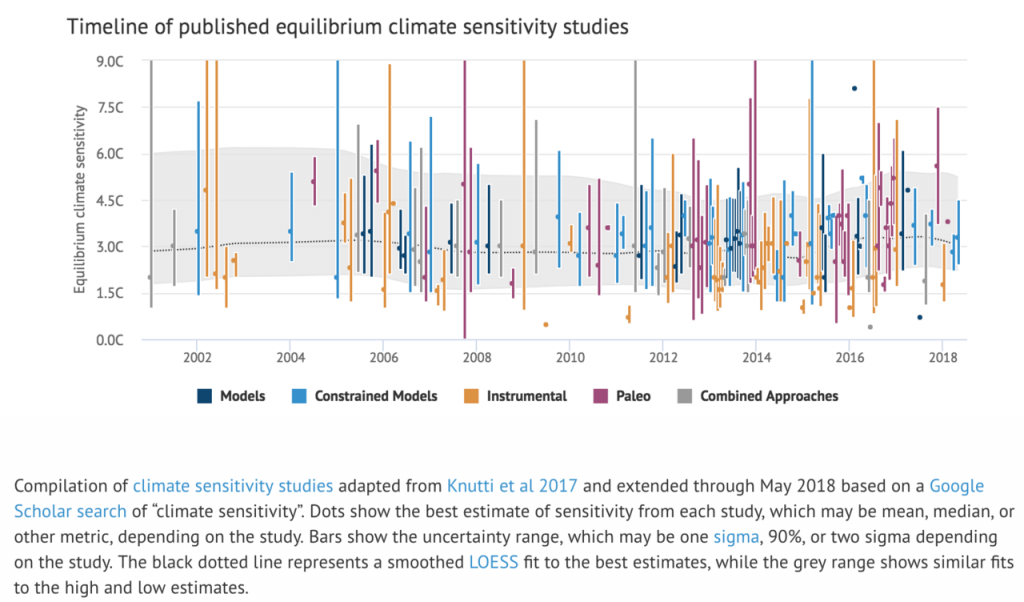

This is only true if you selectively pick studies with low sensitivity. We recently looked at all climate sensitivity studies published using all different methods and found no evidence of an overall decline in estimated ECS in recent years:

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:People who study the impacts of global warming have found that if ECS is low — say, less than two — then the impacts of global warming on the economy will be mostly small and, in many places, mildly beneficial.

This is not necessarily true, as the amount of future warming depends as much on future emissions trajectories as it does on climate sensitivity. A world with 1000 ppm CO2 and an equilibrium climate sensitivity of 2 would still be quite unpleasant.

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:A well-known statistical distribution derived from modeling studies summarizes the uncertainties in this method. It shows that ECS is probably between two and 4.5 degrees, possibly as low as 1.5 but not lower, and possibly as high as nine degrees.

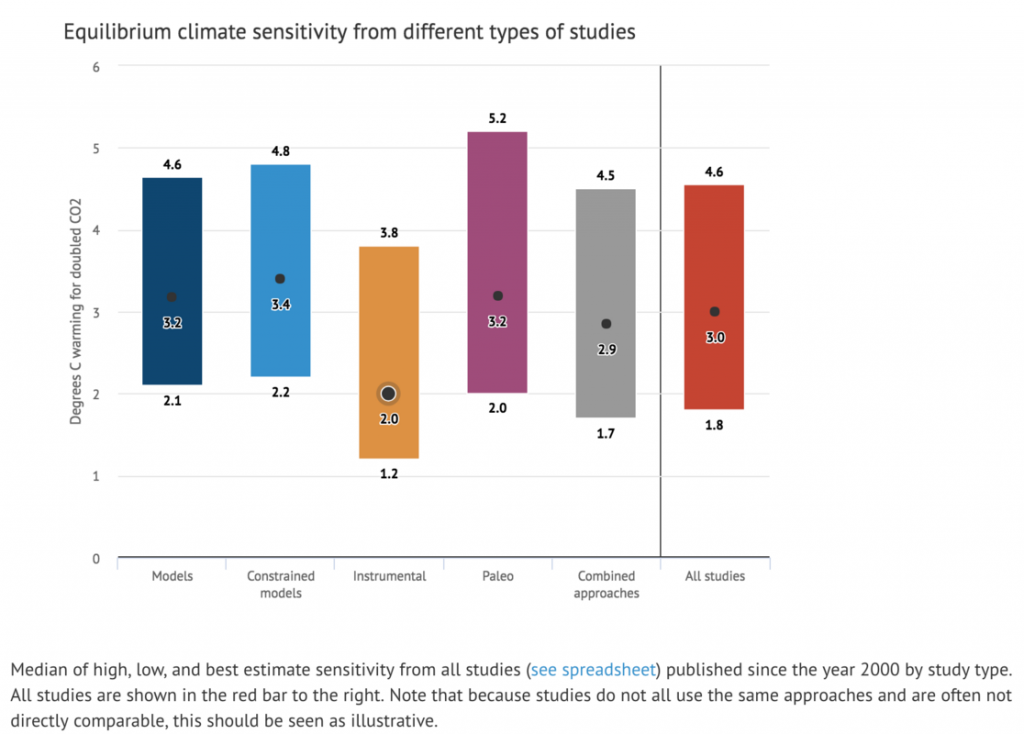

This is not particularly accurate. Virtually no model-based approaches yield equilibrium climate sensitivity estimates below 2 °C, and few yield estimates much above 5 °C. See Knutti et al* for a summary of climate sensitivity studies broken out by study type.

- Knutti et al (2017) Beyond equilibrium climate sensitivity, Nature Geoscience

Reto Knutti, Professor, ETH Zürich:

Uncertainty is not our friend. The fact that the different methods and studies do not fully agree should not be taken as an argument to pick one particular number that one happens to like and discard all the other evidence. As an analogy, when suddenly fog appears on a narrow windy road and the obstacles are hard to see, the normal reaction would be to slow down to be on the safe side, not to accelerate. Greater uncertainty in future warming should be an argument to prepare for the worst case, not to hope for the unlikely case that the impacts will be benign.

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:The surprising thing is that the Energy Balance estimates are very low compared to model-based estimates.

While on average Energy Balance-based approaches (or “instrumental” approaches) tend to give a lower sensitivity than model or paleoclimate results, not all do. See the figure below from Carbon Brief’s recent climate sensitivity explainer, which looks at 143 studies on equilibrium climate sensitivity between 2000 and present:

McKitrick also completely ignores all the climate sensitivity evidence from studies of the Earth’s past climate changes (Paleoclimate), which broadly agrees with the equilibrium climate sensitivity range from climate models.

Reto Knutti, Professor, ETH Zürich:

The text implies that one way to estimate equilibrium climate sensitivity is by using climate models, the other is by using the observed energy budget, and of course the “observed” is claimed to be better. The author fails to understand or convey that there is no way to “observe” climate sensitivity, and all estimates are using a model of some sort, and all models are constrained and evaluated by observations. The energy balance method assumes a simple energy balance framework where feedbacks are independent of timescale, forcing magnitude, and forcing type, which we know is a simplification. In addition is uses radiative forcing as an input that is model derived. It is not obvious that one method is better than the other, but it is clear that all are based on models and observations combined.

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:Climate modelers have put forward two explanations for the discrepancy. One is called the “emergent constraint” approach. The idea is that models yield a range of ECS values, and while we can’t measure ECS directly, the models also yield estimates of a lot of other things that we can measure (such as the reflectivity of cloud tops), so we could compare those other measures to the data, and when we do, sometimes the models with high ECS values also yield measures of secondary things that fit the data better than models with low ECS values.

McKitrick is a bit confused on this point; emergent constraints are useful to narrow down the range of estimates between models, but are not intended to reconcile energy balance/instrumental approaches with other lines of evidence.

Rather, scientists have focused on a number of different shortcomings of instrumental-based equilibrium climate sensitivity estimates. These include using different surface temperature fields (e.g. models use air over oceans, while observations use sea surface temperatures), incomplete data (observations are missing data in much of the Arctic), timescales of feedbacks (instrumental climate sensitivity estimates assume inferred feedbacks over the past few decades remain constant over time, while models show greater feedback magnitudes in the future than in the past), and many other issues. For a summary of these studies see our recent Carbon Brief explainer.

If ECS is as low as the Energy Balance literature suggests, it means that the climate models we have been using for decades run too hot and need to be revised.

Reto Knutti, Professor, ETH Zürich:

The text implies that the models are running too hot. From the period where we have observations, that is simply not correct, the observed warming is within the model range.