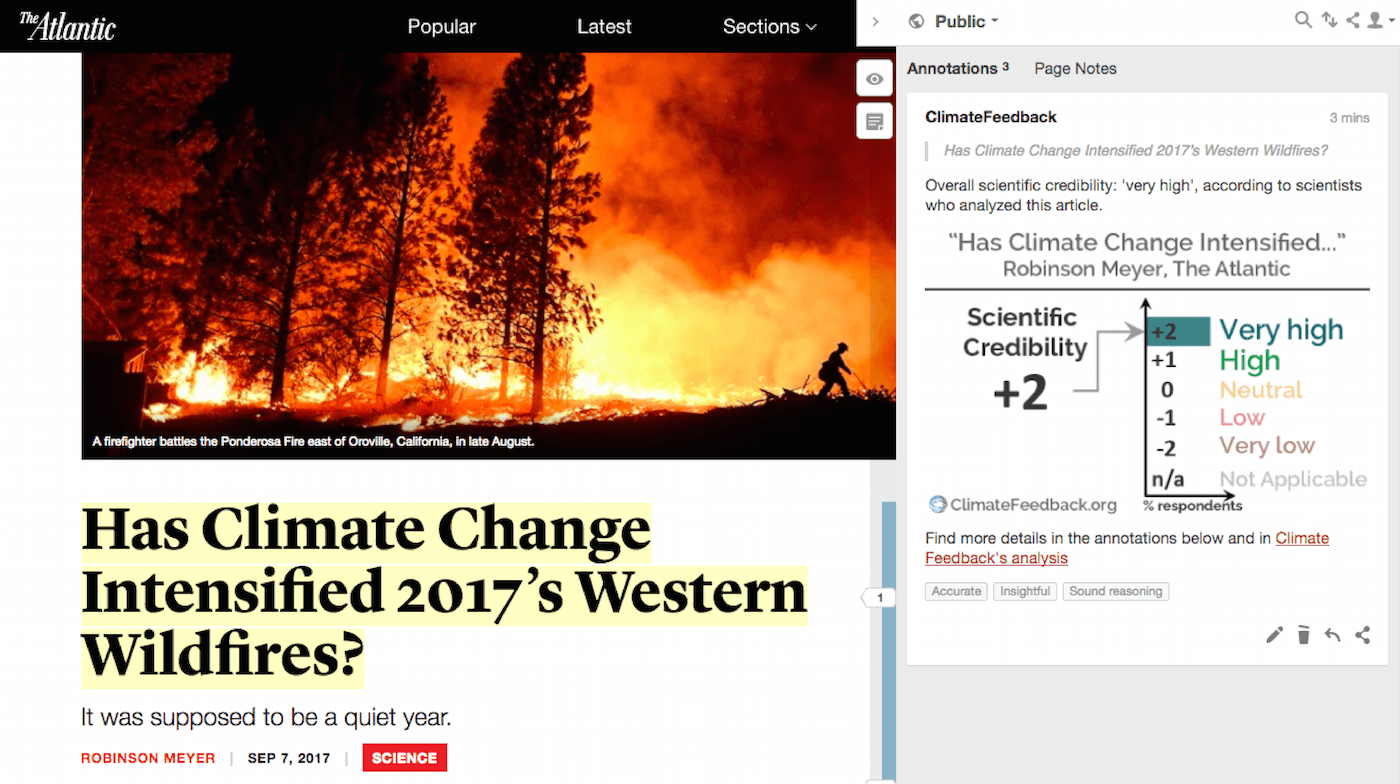

Three scientists analyzed the article and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be ‘very high’. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Accurate, Insightful, Sound reasoning.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This story in The Atlantic describes the conditions that have contributed to this year’s widespread wildfires in the western United States, including the influence of a changing climate.

Scientists who reviewed the story found that it was an accurate summary of the factors involved in this fire season—warm temperatures as well as past fire-suppression practices that have increased the density of fuel available for fires to burn.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Logan Berner, Assistant Research Professor, Northern Arizona University:

The article provides an excellent summary of how rising air temperatures are leading to drier conditions and more fire activity among forests in parts of the western United States. The article is strengthened by including multiple interviews with scientists who have produced seminal studies of fire-climate interactions in this region. One minor error is that the “paper published in Science last year” was actually published in 2006, not 2016, yet this oversight detracts little from the overall accuracy of the article.

Ben Poulter, Research Scientist, NASA:

The article highlights clearly the challenges that scientists and managers face in disentangling how changes in ignitions, fuel loading, past-management legacies and climate interact to start and sustain fires.

William Anderegg, Associate Professor, University of Utah:

The article is well-supported by the peer-reviewed literature.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

FEATURED ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“How did a wet Western winter lead to a sky-choking summer?

The answer lies in the summer’s record-breaking heat, say wildfire experts. Days of near-100-degree-Fahrenheit temperatures cooked the Mountain West in early July, and a scorching heat wave lingered over the Pacific Northwest in early August.”

Logan Berner, Assistant Research Professor, Northern Arizona University:

Exceptionally high summer air temperatures undoubtedly contributed to the extensive forest fire activity that occurred during the summer of 2017 in the western United States. Forest flammability is affected by both winter snowfall and seasonal rain, as well as by spring and summer air temperatures that regulate the timing of snowmelt and how much water the atmosphere will suck out of the forest.

“the total area burned in the western United States over the past 33 years was double the size it would have been without any human-caused warming.”

Anthony LeRoy Westerling, Associate Professor, University of California, Merced:

I would say: “the total area burned in the western United States over the past 33 years was at least double the size it would have been without any human-caused warming.”

“Fires have not only been increasing in size due to climate change. In the early 20th century, state and federal governments began aggressively fighting wildfires and trying to keep them as small as possible. This has caused denser and more fire-prone forests than the long-term average for the West, which has led to more massive and uncontrollable fires.”

Logan Berner, Assistant Research Professor, Northern Arizona University:

This statement should have included a citation and also noted that the influence of fire suppression on subsequent fire activity varies with the frequency of historical fires. The century of fire suppression has potentially increased fuel accumulation in dry forests that historically experienced very frequent fires (e.g. every 5-20 years). On the other hand, fire suppression has likely had far less of an impact on wetter forests, such as those in coastal Oregon and Washington, that historically went centuries without fire.