Thirteen scientists analyzed the article and estimated its overall scientific credibility to be ‘high’ to ‘very high’. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Accurate.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This article in The New York Times serves as a primer by briefly answering seventeen basic questions about the cause and consequences of—and possible solutions to—climate change.

Thirteen scientists reviewed the article, and generally found the answers to be highly accurate distillations of the research on that topic. There are only a few instances where answers—mainly to questions about efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—are worded in an imprecise way that could lead to readers misunderstanding the state of scientific knowledge.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

This is part of a series of reviews of 2017’s most popular climate stories on social media.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Ted Letcher, Research Scientist, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab:

The article provided a quick and remarkably concise “listicle” style explanation of the key questions surrounding climate change. I saw no red flags, or blatant attempts to mislead the reader. Furthermore, every major scientific claim has a link to a peer reviewed article.

The article largely avoids hyperbole as well as alarmist and inflammatory language, which is laudable. I also want to highlight the section that talks about the various solutions and opportunities for action.

Overall, a good article that hits all the key point, speaks in plain English, and treats the reader with enough respect to look deeper into any one issue.

Joeri Rogelj, Research Scholar, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA):

The article provides a fair and correct account of the state of the science in my area of expertise. Some statements could be slightly more informative when the article speaks about “experts”. It is not clear who these experts are. In some cases “expert” views are used to support statements which are dependent on societal value judgments, and would benefit from some clarification.

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

The accuracy of the climate information provided in this piece is generally quite high. Further, the “question and answer” format distills complex, ongoing scientific conversations into a form more readily accessible to a broad audience.

Benjamin Horton, Professor, Earth Observatory of Singapore:

Climate change is one of the most complex areas of scientific study, so it is understandable that the general public find the topic difficult to grasp. But this article provides the readers of The New York Times the chance of understanding the topic.

Lennart Bach, Postdoctoral research fellow, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel:

The article is well written. The author used little “alarmist” jargon and used “strong” adjectives only in cases where there is good scientific evidence for strong impacts.

Devaraju Narayanappa, Postdoctoral research fellow, Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin (UVSQ-CEA-CNRS):

The article provides a simple answer to overarching questions on global warming/climate change and its footprints.

Malte Stuecker, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Washington:

The article presents short but accurate statements on climate change and its framing.

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

As far as I can judge, very accurate. A pleasure to read. There should be more science reporting like this.

Frank Vöhringer, Dr. rer. pol, Scientist, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL):

The article provides an informative overview of climate and climate policy facts with only minor inaccuracies.

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

Overall the article frames the questions correctly and provides generally good answers. However, it presents some aspects in a rather simplified and incomplete manner (e.g. consequences of global warming or mitigation solutions).

Didier Swingedouw, Researcher, CNRS (French National Center for Scientific Research):

The article is mainly accurate for most of its assertions. Some of them are bit subjective and possibly alarmist, but generally speaking the author is very well informed concerning general understanding that we have of global warming and its impact (as released in IPCC report for instance).

Dan Jones, Physical Oceanographer, British Antarctic Survey:

Although there are places where the language is a little imprecise (e.g. the word “ever” in the statement “Geologists say that humans are now pumping the gas into the air much faster than nature has ever done”), overall the article is an accurate, concise summary of climate change as a scientific and social issue.

Kelly McCusker, Research Associate, Rhodium Group and Climate Impact Lab:

The article does a good job of succinctly answering complex questions without misrepresenting the scientific evidence.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

FEATURED ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

How much is the Earth heating up?

“Climate change? Global warming? What do we call it? […]You can think of global warming as one type of climate change. The broader term covers changes beyond warmer temperatures, such as shifting rainfall patterns.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

This is a good way to describe the difference in language. It would also be reasonable to say that global warming (the increase in Earth’s average temperature) causes climate change (shifts in the location/frequency/intensity of weather patterns). In practice, the two terms are often used somewhat imprecisely and interchangeably (even in the scientific literature).

Kelly McCusker, Research Associate, Rhodium Group and Climate Impact Lab:

It is also worth noting that global warming refers to global average temperature rising, but this does not necessarily mean that all locations across the globe are warming at all times.

“the oceans are rising at an accelerating pace”

Kelly McCusker, Research Associate, Rhodium Group and Climate Impact Lab:

Because more than 90% of the energy added to the climate system is being stored in the ocean, causing sea level rise through thermal expansion. The latest IPCC report states, “Ocean warming dominates the increase in energy stored in the climate system, accounting for more than 90% of the energy accumulated between 1971 and 2010 (high confidence).”

“Two degrees is more significant than it sounds. […]The number may sound low, but as an average over the surface of an entire planet, it is actually high”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

This is an important point. “Global mean temperature” (GMT) is a pretty abstract quantity, since it doesn’t reflect any particular location on Earth. Instead, GMT serves as a useful indicator of how much the Earth’s climate has changed overall. While a helpful statistical construct, it masks the fact that the Earth is warming much faster than the global average in some regions (over land, in the Arctic) than in others (over the oceans).

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

Note that the warming over land is about twice as large as the warming over the ocean. Over the ocean, more of the additional heat goes into evaporation of water rather than warming of the air. It furthermore takes time to heat up the oceans, just like a water kettle takes time to boil.

Because there is more land in the Northern Hemisphere, it will warm more than the Southern Hemisphere.

One way to see how much of a difference two degrees makes is to look at a region closer to the equator that is two degrees warmer. Nature will look very different.

“We’ve known about [the greenhouse effect] for more than a century. Really.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

As the author correctly notes, the underlying chemistry dates back to the late 1880s.

“The first prediction that the planet would warm as humans released more of the gas was made in 1896.”

Ed Hawkins, Principal Research Fellow, National Centre for Atmospheric Science:

Arrhenius didn’t actually discuss human emissions in 1896—he was speculating about causes of the ice ages. But, he did effectively make a prediction that warming would occur if carbon dioxide levels increased (whatever their source).

“[CO2] has increased 43 percent above the pre-industrial level so far”

Lennart Bach, Postdoctoral research fellow, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel:

Indeed! I get to a slightly different number, however, (45 %) maybe because I used a different basis (280 ppm) and/or current CO2 value (i.e., 405 ppm from Maona Loa, August 2017). The message is correct!

How do we know humans are responsible for the increase in carbon dioxide?

“Hard evidence, including studies that use radioactivity to distinguish industrial emissions from natural emissions, shows that the extra gas is coming from human activity.”

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

Also important is that we have good estimates of how much fossil fuel we have burned, from which one can estimate the CO2 emissions. The increase in CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is about half of those emissions (the rest was taken up by the vegetation and the oceans).

It would have been more accurate to say that we can see that the CO2 increase is from burning fossil fuels by measuring isotopes (differences in the number of nuclear particles of atoms). Not all relevant isotopes are radioactive and the ones that are only a little.

“Geologists say that humans are now pumping the gas into the air much faster than nature has ever done.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

“Ever” is a long time, and it’s not clear this is strictly true for the entire length of Earth’s history. But there is strong evidence that this statement is true for all human-relevant timescales: in other words, the rate of CO2 emissions caused by humans is unprecedented since the age of the dinosaurs (i.e., at least 66 million years ago*).

- Zeebe et al (2016) Anthropogenic carbon release rate unprecedented during the past 66 million years, Nature

Could natural factors be the cause of the warming?

“Could natural factors be the cause of the warming? Nope.”

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

We are sure that natural factors alone could not have caused the observed warming—without the increase of greenhouse gases there would not be so much warming—but they could have contributed.

For the period 1951 to 2010 our best estimate is that all of the warming was due to human activities. But natural factors could have warmed or cooled the Earth a bit. In the period around 1900, part of the warming was probably natural due to fewer volcanic eruptions and a stronger Sun.

[Also see this related Claim Review. ]

“The warming is extremely rapid on the geologic time scale, and no other factor can explain it as well as human emissions of greenhouse gases.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

This accurate statement succinctly summarizes decades of scientific research across a wide range of disciplines.

Why do people deny the science of climate change?

“Instead of negotiating over climate change policies and trying to make them more market-oriented, some political conservatives have taken the approach of blocking them by trying to undermine the science.”

Victor Venema, Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany:

This is mostly just in the USA. In the rest of the world, conservative parties accept the science of climate change.

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

On the scientific community side, the consensus is broad. It’s worth revisiting Cook et al. 2015*. In their review they find a 97% consensus about human-induced global warming in published climate studies.

- Cook et al (2016) Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming, Environmental Research Letters

What could happen?

“Over the coming 25 or 30 years, scientists say, the climate is likely to gradually warm”

Ted Letcher, Research Scientist, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab:

While the exact details and timing of warming are subject to unpredictable decadal (semi-decadal) climate variability (e.g. El Niño Southern Oscillation, Pacific Decadal Oscillation, Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation), this statement is largely true.

“Longer term, if emissions rise unchecked, scientists fear climate effects so severe that they might destabilize governments, produce waves of refugees, precipitate the sixth mass extinction of plants and animals in the Earth’s history, and melt the polar ice caps, causing the seas to rise high enough to flood most of the world’s coastal cities. The emissions that create those risks are happening now, raising deep moral questions for our generation.”

Ed Hawkins, Principal Research Fellow, National Centre for Atmospheric Science:

This paragraph suggests that the emissions that will precipitate the sixth mass extinction are happening now, which I think is misleading. We can stop those impacts by reducing our emissions.

How much will the seas rise?

“The ocean has accelerated and is now rising at a rate of about a foot per century[…] The risk is that the rate will increase still more. Scientists who study the Earth’s history say waters could rise by a foot per decade in a worst-case scenario, though that looks unlikely. Many experts believe that even if emissions stopped tomorrow, 15 or 20 feet of sea level rise is already inevitable, enough to flood many cities unless trillions of dollars are spent protecting them. How long it will take is unclear. But if emissions continue apace, the ultimate rise could be 80 or 100 feet.”

Benjamin Horton, Professor, Earth Observatory of Singapore:

It is accurate to say sea-level rise is approximately one foot per century. Present-day sea-level rise is a major indicator of climate change. Since the early 1990s, sea level rose at a mean rate of ~3.1 mm/yr (~1 foot over 100 years).

It is virtually certain that global mean sea level rise will continue for many centuries beyond 2100, with the amount of rise dependent on future emissions. The latest IPCC report estimates 1 to more than 3 m (up to ~10 feet) for high emission scenarios by 2300. But, those projections of sea-level rise may be limited by uncertainties surrounding the response of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. For example, the report projected a likely contribution of the Antarctic ice sheet (AIS) of -8 to +15 cm under the high emissions scenario by 2100, but a recent coupled ice sheet and climate dynamics model suggests that the AIS could contribute more than 1 m by 2100, and more than 10 m by 2300, under that high emissions scenario.

Is recent crazy weather tied to climate change?

“Is recent crazy weather tied to climate change? Some of it is.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

This is a reasonable short answer to an extremely challenging scientific question.

“Scientists have published strong evidence that the warming climate is making heat waves more frequent and intense. It is also causing heavier rainstorms”

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

It is hard to attribute each particular event to human-induced climate change. The article correctly frames the influence in terms of increasing frequency and intensity of extremes, and directs the reader to a good reference page with clear explanations for non-experts.

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

Indeed, there is now observational evidence that global warming has already increased the likelihood and magnitude of extreme heat and intense downpours across much of the globe*.

- Diffenbaugh et al (2017) Quantifying the influence of global warming on unprecedented extreme climate events, PNAS

“In many other cases, though — hurricanes, for example — the linkage to global warming for particular trends is uncertain or disputed.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

The question of whether global warming will affect the frequency of hurricanes is indeed an open one, and research continues. There is stronger evidence, however, that warming will increase the maximum “intensity ceiling”/intensification rate1 of the strongest storms, the maximum rainfall associated with tropical cyclones2, and the magnitude of oceanic “storm surges”3 that occur in an era of rising seas.

- 1- Emanuel (2017) Will Global Warming Make Hurricane Forecasting More Difficult?, BAMS

- 2- Scoccimarro et al (2017) Tropical Cyclone rainfall changes in a warmer climate

- 3- Lin et al (2016) Hurricane Sandy’s flood frequency increasing from year 1800 to 2100, PNAS

Are there any realistic solutions to the problem?

“But as long as there are still unburned fossil fuels in the ground, it is not too late to act.”

Joeri Rogelj, Research Scholar, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA):

This statement is imprecise, and depends on value judgments of what “too late” means. Even emitting only a fraction of the available unburned fossil fuels would eliminate important ecosystems like coral reef habitats. For these ecosystems it will thus be too late. Because part of the CO2 that is emitted will remain in the atmosphere for many centuries, climate change constitutes a cumulative problem. Halting CO2 emissions before the last fossil fuel has been burned thus indeed commits the world to less impacts than the theoretically maximum. However, whether this is not “too late” depends on whether no irreversible or societally unacceptable impacts were reached before that point. The latter requires societal value judgments informed by scientific assessments, but is ultimately not a scientific question.

Frank Vöhringer, Dr. rer. pol, Scientist, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL):

This is incorrect, at least if we want to stay anywhere near the 2 degree C target. Especially coal reserves are so abundant (and there is coal gasification and coal liquefaction) that by far the largest part of them have to stay in the ground.

“The warming will slow to a potentially manageable pace only when human emissions are reduced to zero.”

Joeri Rogelj, Research Scholar, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA):

The current understanding of interactions between the global carbon cycle and the climate system is that when global CO2 emissions are reduced to zero, the warming will remain approximately constant. This is very often confused by estimates of committed “warming in the pipeline” which instead of assuming that global emissions are reduced to zero, assume that concentrations (and therewith to a large degree forcing) are kept constant. Keeping CO2 concentrations constant would require continuous emissions of CO2 that perfectly counter the uptake by natural sinks. If CO2 emissions are reduced to zero, atmospheric CO2 concentrations will gradually decline. For heat-trapping emissions other than CO2, the requirement to reduce them to zero to stabilize warming depends on their residence time in the atmosphere. For gases and particles that only stay in the atmosphere for shorter time periods (days to a decade) achieving constant emissions would also achieve approximately stabilized warming.

“But experts say the energy transition needs to speed up drastically to head off the worst effects of climate change.”

Joeri Rogelj, Research Scholar, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA):

This is correct. While many countries show gradual declines in their emissions, global emissions are not yet declining. The past few years, global annual CO2 emissions have not increased as much as they did previously and remained roughly constant. However, to halt global mean temperature rise annual CO2 emissions have to become zero.

Does clean energy help or hurt the economy?

“Converting to these cleaner sources [of energy] may be somewhat costlier in the short term, but they could ultimately pay for themselves by heading off climate damages and reducing health problems associated with dirty air.”

Kenneth Gillingham, Associate Professor, Yale University:

The basic idea of this sentence is correct—that these cleaner sources may be somewhat costlier in the short run, but they also provide benefits that offset the short-run costs. The second part of the sentence is technically correct given that it uses the word “could,” which provides a lot of leeway. A more complete story is that a switch towards these cleaner technologies on the margin for electricity would pay for itself given reasonable estimates of the health costs of fossil fuel generation and the social cost of carbon. It’s also worth noting though that an immediate switch entirely to these technologies would incur transition costs that would likely tip the balance in the cost-benefit analysis, depending on the social cost of carbon used and what sectors we are talking about (are we talking about just electricity? industry? transport?). The vagueness of the statement means that it is less meaningful, but more difficult to critique.

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

The article does not mention the huge subsidies to the fossil fuel industry worldwide. According to the World Energy Outlook 2016, fossil-fuel subsidies were around $325 billion in 2015 ($490 billion in 2014) against 150 billion for renewables.

“Burning gas instead of coal in power plants reduces emissions in the short run, though gas is still a fossil fuel and will have to be phased out in the long run.”

Frank Vöhringer, Dr. rer. pol, Scientist, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL):

It is arguable whether natural gas is a reasonable solution even in the short run. I argued in favor of this 20 years ago, but nowadays we have to cut emissions more drastically than would be possible by switching to another fossil fuel. The CO2 coefficient of natural gas is still about 2/3 of that of coal. Efficiency factors of power plants are also somewhat better for natural gas than for coal. Overall, we might save a bit more than half of the emissions by switching to natural gas while renewables can save much more. Furthermore, given the long technical lifetime of power stations, the “short run” could easily extend to 2060 or more.

“‘Clean coal’ is an approach in which the emissions from coal-burning power plants would be captured and pumped underground.”

Joeri Rogelj, Research Scholar, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA):

It is important to note that up to the present, the capture of CO2 is not perfect. While theoretically some CO2 emissions could be avoided, a residual amount would still leak into the atmosphere. As CO2 accumulates in the atmosphere, it would either lead to continued (yet slower) warming, or have to be compensated by the active removal of CO2 from the atmosphere, which is also not yet proven to work economically.

“some countries are already talking about banning the sale of gasoline cars after 2030”

Frank Vöhringer, Dr. rer. pol, Scientist, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL):

It’s not only talk. Great Britain has already decided in favor of such a ban by 2040.

Climate change seems so overwhelming. What can I personally do about it?

“Experts say the problem can only be solved by large-scale, collective action”

Kenneth Gillingham, Associate Professor, Yale University:

This is correct. Our atmosphere is a global public good and addressing the issue requires large-scale action by most players.

“Entire states and nations have to decide to clean up their energy systems”

Kenneth Gillingham, Associate Professor, Yale University:

This is correct. It cannot be done by only a few nations—it requires collective action to make a substantial difference.

“Entire states and nations have to decide to clean up their energy systems, using every tool available and moving as quickly as they can.”

Kenneth Gillingham, Associate Professor, Yale University:

This is not universally agreed upon by experts. The key issue is that it is imprecisely written. I would not be surprised if the intent is correct. But taking it as it is written, it is not clear what “every tool available” includes. Technically, this should include truly everything, including simply shutting down all manufacturing that uses fossil fuels at all. Banning the driving of any vehicle except electric vehicles run on renewables. Banning flying. I doubt that was the intent of the sentence. The same issue holds for “moving as quickly as they can.” What are the limits to”as quickly as they can”? Does it including shutting down the economy? Or is the intended sentence “moving as quickly as they cost-effectively can”? Thus, in short, while the idea is correct, this is imprecisely worded and can easily be critiqued.

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

“Using every tool available” is highly debatable, as even tools which are usually perceived to help mitigating climate (e.g. reforestation), may not result in mitigation effects, depending on how they are implemented. A study on European forests* has shown that afforestation since 1750 was responsible for an increase of 0.12 watts per square meter in the radiative imbalance at the top of the atmosphere, rather than a decrease, because of management choices.

- Naudts et al (2016) Europe’s forest management did not mitigate climate warming, Science

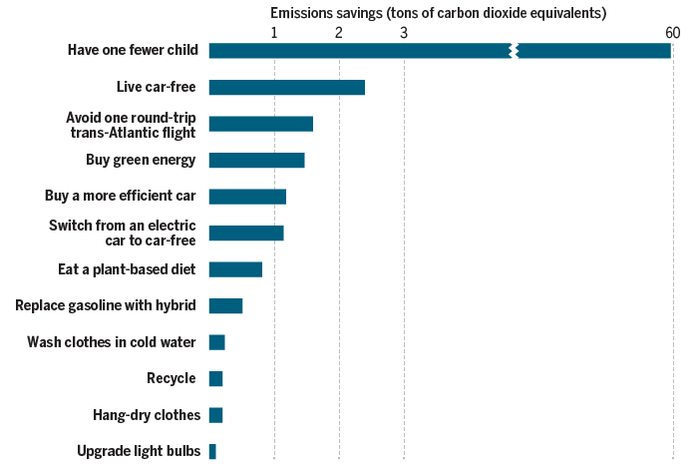

“You can plug leaks in your home insulation to save power, install a smart thermostat, switch to more efficient light bulbs, turn off unused lights, drive fewer miles by consolidating trips or taking public transit, waste less food, and eat less meat.”

Ana Bastos, Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry:

According to a recent study*, having fewer children has the largest impact on personal carbon footprint.

- Wynes and Nicholas (2017) The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions, Environmental Research Letters