Seven scientists analyzed the article and estimated its overall scientific credibility to be ‘very low’. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Cherry-picking, Flawed reasoning, Inaccurate, Misleading.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

The Telegraph published a brief article by Christopher Booker discussing recent Arctic temperatures and sea ice cover in the context of climate change. It is largely based on claims made in a blog post that refers to data from the Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI). But DMI scientists explain that the article “fundamentally misrepresents both our research and the operational data products we provide”.

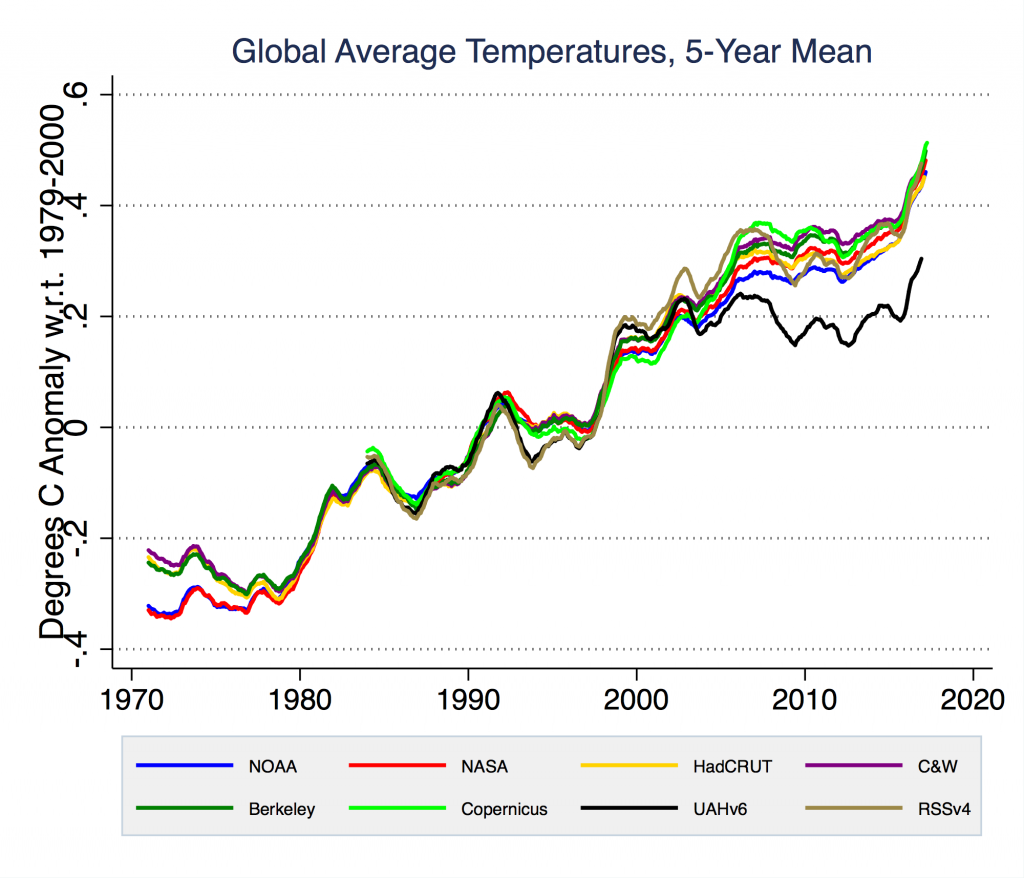

The scientists who have reviewed the article indicate that its claims are misleading or inaccurate. For instance, the article emphasizes that global average temperature has decreased since the end of the 2016 El Niño event, which was expected, but fails to note that this recent decrease by no means reverses the long-term increase in temperature. It also inaccurately claims that global temperature has not warmed over the past 19 years—in direct contradiction with observations. The author claims that last winter in the Arctic was “cold” (-20°C), but fails to recognize that this temperature is much warmer than the norm for the Arctic (by about 5°C), making it the second warmest winter on record.

[This article has been used as a reference by another article in the Daily Wire, which expands on false claims made in this Telegraph article.]

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

GUEST COMMENTS

Ruth Mottram, Martin Stendel, Peter Langen, Danish Meteorological Institute

(with contributions from Mads Ribergaard and Gorm Dybkjær)

The articles in The Telegraph and The Daily Wire fundamentally misrepresent both our research and the operational data products we provide freely to the public. Below are the details of where the Telegraph and the Daily Wire stories are misleading or simply wrong based on our data.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Dan Jones, Physical Oceanographer, British Antarctic Survey:

This article suffers from a common error in reasoning. The author focuses on individual “snapshots” of the state of the climate while ignoring the long-term trends. Those trends occur over many decades and must be observed/considered over those time scales.

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

This paper peddles common misconceptions about climate change to suggest that global warming is not a problem. It’s extremely misleading and can be easily debunked based on peer-reviewed literature.

William Anderegg, Associate Professor, University of Utah:

This article is highly misleading and factually inaccurate.

Jan Lenaerts, Assistant Professor, University of Colorado, Boulder:

This article mixes short-term weather phenomena and long-term climate trends, and uses logical fallacies and cherry-picked evidence to make a false claim.

Alek Petty, Postdoctoral associate, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center:

Terrible article: Making up facts, cherry picking data, consulting non-scientists, and spouting nonsense.

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

For its short length, this article contains an impressive number of falsehoods and willful misinterpretations of data. Essentially all the climate-related claims therein are either demonstrably false or “cherry picked.”

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“ever since December temperatures in the Arctic have consistently been lower than minus 20 C”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

It is indeed true that the Arctic is cold in winter—it’s hard to argue with that. But this statement belies the fact that winter 2017 was actually extraordinarily warm by historical standards, and second only to the record-shattering warmth observed just last year (in 2016). The attached plot, created by Zachary Labe and available at http://sites.uci.edu/zlabe/arctic-temperatures, shows that the -20 °C temperatures this winter are nearly 10 °C degrees above the long-term average of -30 °C! Therefore, the fact that temperatures were -20 °C this winter in the Arctic is actually a testament to just how much the Arctic has warmed in recent years.

(with contributions from Mads Ribergaard and Gorm Dybkjær)

This statement is both wrong and misleading.

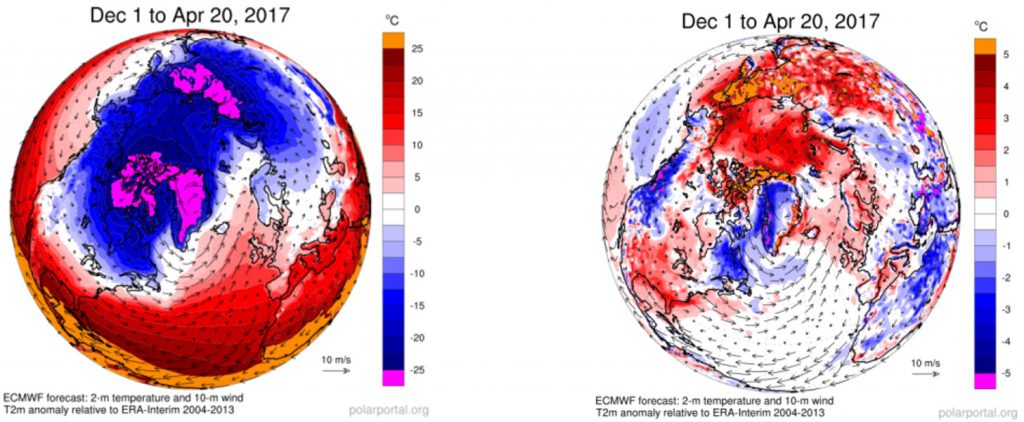

Firstly, most of the Arctic has in fact been consistently warmer than -20 °C this winter. For the period 1 December 2016 to 20 April 2017, the average temperature was above -20 °C everywhere in the central Arctic except north of Greenland and the Canadian Archipelago. Over the Greenland Ice Sheet and in Eastern Siberia (and only there), the temperature was below -25 °C.

Secondly, it should not be a surprise that the Arctic is very cold in winter (a period with little to no sunlight). It is much fairer to consider the difference between this winter and the average winter temperatures. Compared to our baseline of 2004-2013 everywhere in the Arctic region was at least 4 °C warmer than the average of 2004-2013 (in itself a warmer baseline period than the 1958-2002 baseline used elsewhere). Around Svalbard, it was about 4.5 °C warmer than average and in Northern Greenland, including Kap Morris Jesup, the world’s northernmost weather station (where a record +3 °C temperature was recorded on one day in February), Ellesmere Island in northeastern Canada, and large parts of eastern Siberia this winter were more than 5 °C warmer than the average as you can see below:

Figure: Left, Average temperature over the Arctic for the period December 2016 to April 2017; Right, Deviation of temperature for the period December 2016 to April 2017 from the average 2004-2013.This makes the winter 2016/2017 the second warmest on record in the Arctic (after winter 2015-16), according to the European Copernicus climate service.

Figure: Left, Average temperature over the Arctic for the period December 2016 to April 2017; Right, Deviation of temperature for the period December 2016 to April 2017 from the average 2004-2013.This makes the winter 2016/2017 the second warmest on record in the Arctic (after winter 2015-16), according to the European Copernicus climate service.

“record temperatures brought in 2016 by an exceptionally strong El Niño”

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

Last year the annual global temperature was about 1.1 °C above a late-19th century baseline but only about 0.1°C of this was due to the El Niño—the other 1 °C is due to human influences.

So while the record occurred in 2016 due to El Niño, most of the anomaly was due to climate change.

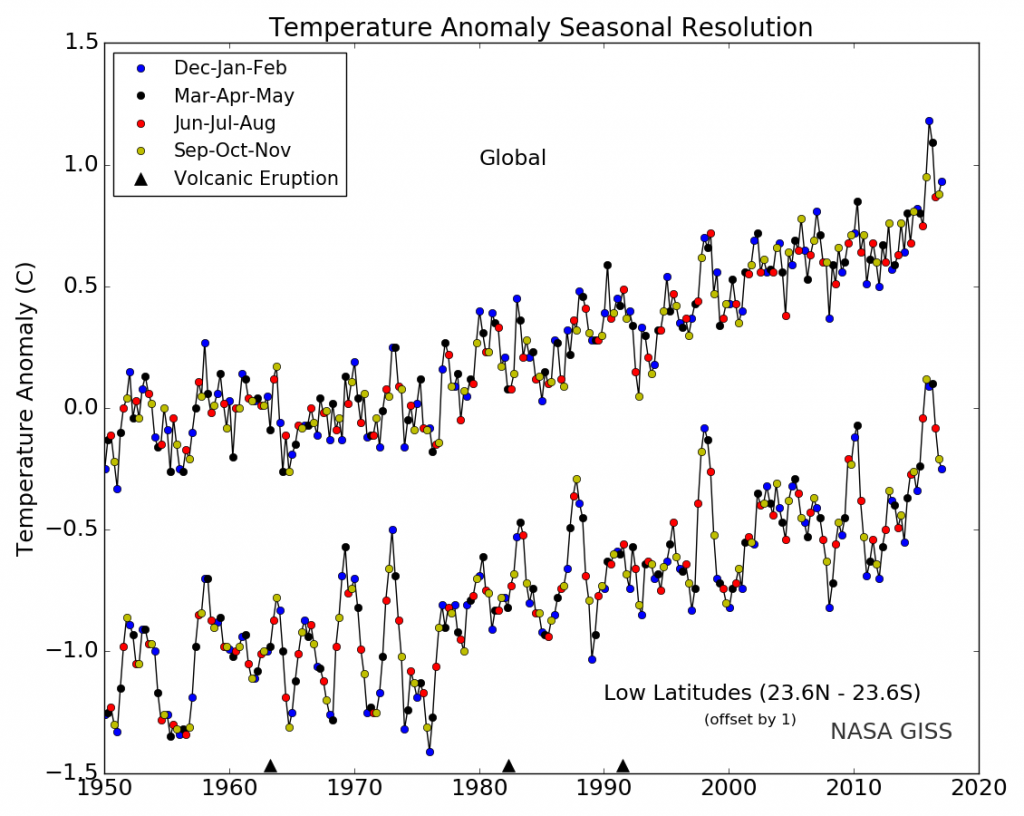

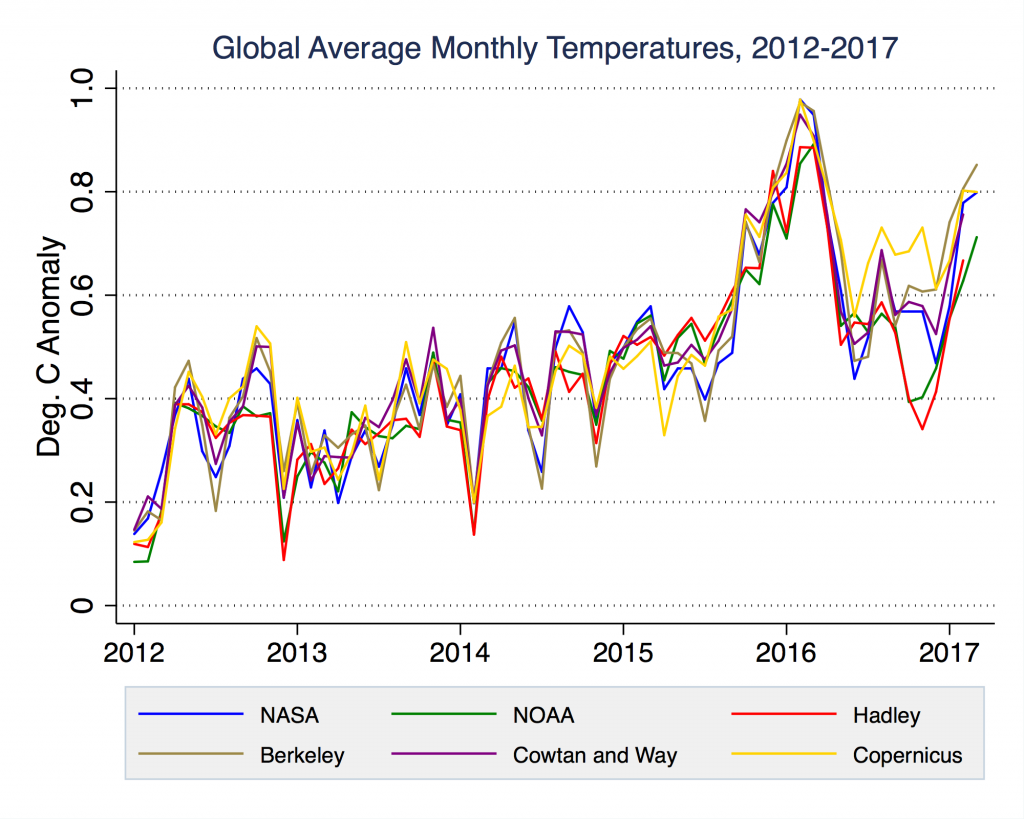

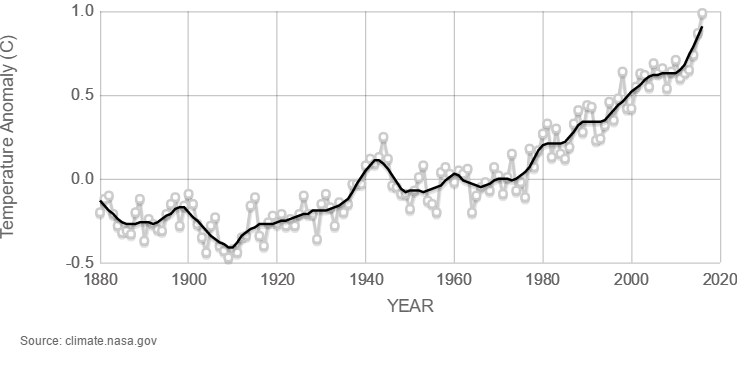

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:“the satellites now show that in recent months global temperatures have plummeted by more that [sic] 0.6 degrees”

El Niño events do indeed elevate global temperatures temporarily, and this is partly why global temperatures in 2016 were so extreme. But as the attached plot from NASA GISS shows, temperatures so far in 2017 have still been extraordinarily warm in a historical context, and in fact would have been record-breaking if not for the large temperature spike that occurred in 2016. In any case, it is not scientifically meaningful to measure global temperature “trends” over a two year period; the large and statistically significant long-term warming signal overwhelms short-term variations on multi-decadal timescales.

William Anderegg, Associate Professor, University of Utah:

While true (and not necessarily in agreement with the more robust thermometer records for this period, this has no bearing on the long-term climate trend, which is driven by human emissions of greenhouse gases. It is misleading and a logical fallacy to claim this says anything about climate change, which is the long-term change in temperatures.

Zeke Hausfather, Director of Climate and Energy, The Breakthrough Institute:

While temperatures have declined modestly from the peak of the El Niño event, this is expected behavior, particularly in satellite records where El Niño is amplified. However, temperatures in January through April are quite above average to-date, and while we may not set a record temperature in 2017 compared to 2016, it will very likely be the second warmest year on record (at least on the surface).

Through present there is no sign of any sort of pause or slowdown in any of the surface records or one of the two satellite records (the RSS groups latest version 4 record). The only record showing a continued pause is the one produced by the University of Alabama, Huntsville (the UAH record).

The differences between these records and their causes is an area of active research, though we have strong reason to suspect that the surface record is quite accurate.

“This means the global temperature trend has now shown no further warming for 19 years”

Andrew King, Research fellow, University of Melbourne:

This is both cherry-picking of the data (starting with 1998), and not correct anyway.

William Anderegg, Associate Professor, University of Utah:

This is blatantly false. Examine the trend here:

Furthermore, a short time period of a few months in 2017 cannot say anything whatsoever about the long-term change in climate.

Andreas Schmittner, Associate Professor, Oregon State University:

This statement is false. Global temperatures continue their long-term warming trend.

“In April the extent of Arctic sea ice was back to where it was in April 13 years ago”

Ed Hawkins, Principal Research Fellow, National Centre for Atmospheric Science:

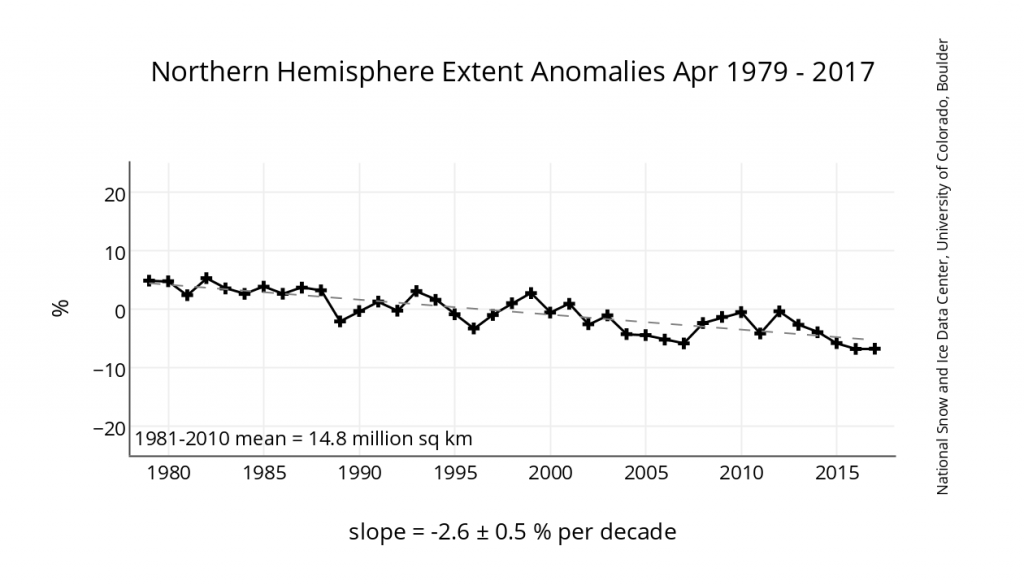

In the NSIDC dataset, April 2017 was actually the equal of the lowest Northern Hemisphere extent on record (tied with 2016 on 13.83 M km2).

This statement is misleading. Arctic sea ice extent in April was significantly lower than the long-term average—but varies substantially from day to day and year to year as processes such as wind and waves and short-term weather variability have a substantial effect on sea ice extent, particularly at this time of year. However, over the long term since 1979, the April sea ice extent has declined by around 3% per decade, at other times of the year the decline is even more marked. This is an example of cherry-picking dates in order to try and state that the sea ice is recovering (it’s not). It also confuses climate variability with trends over short periods.

“Furthermore, whereas in 2008 most of the ice was extremely thin, this year most has been at least two metres thick.”

Daniel Swain, Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles:

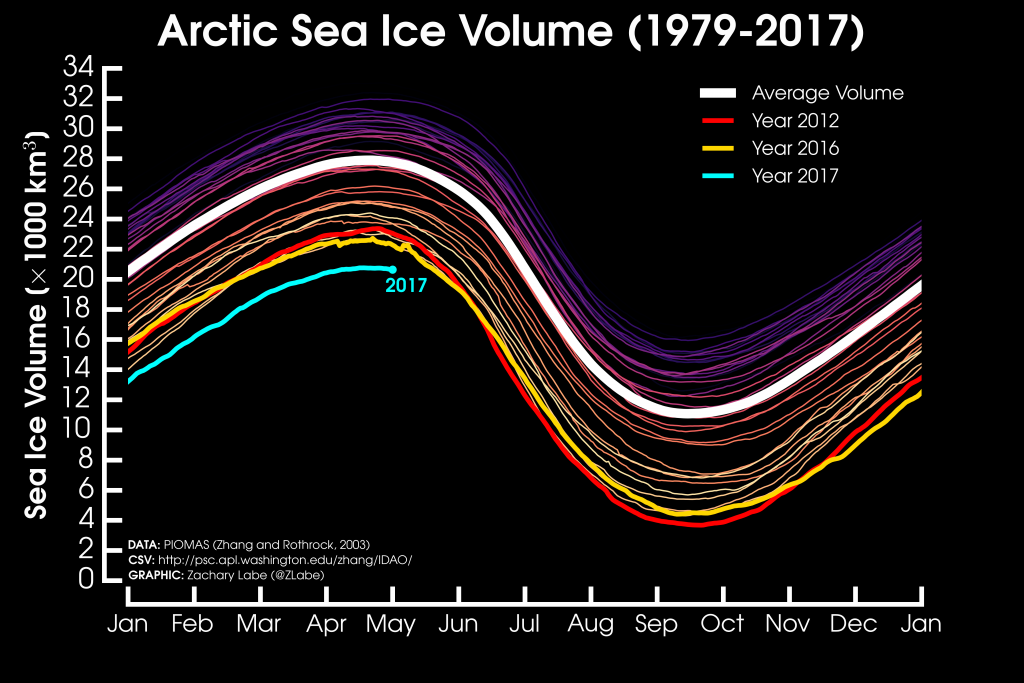

Arctic sea ice volume has actually exhibited record thinness so far during 2017—beating the previous record years of 2012/2016 by a wide margin. Another nice visualization by Zachary Labe illustrates this quite clearly:

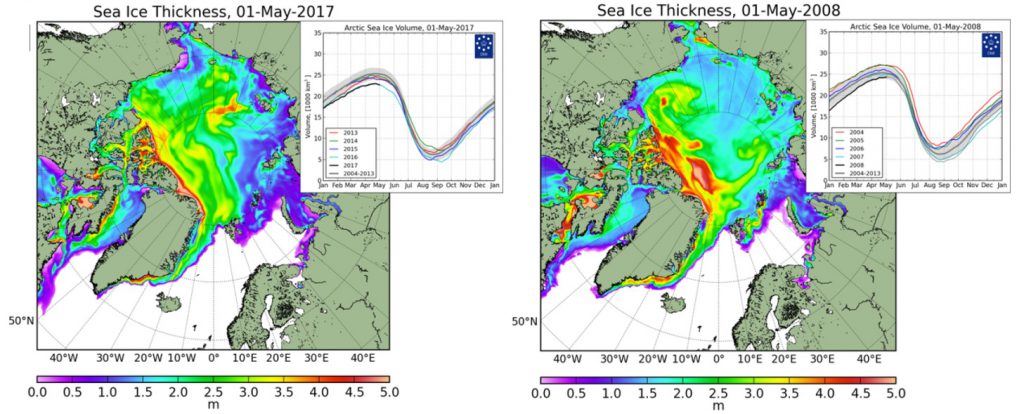

“Whereas in 2008 most of the ice was extremely thin, this year most has been at least two metres thick.”

Ruth Mottram, Martin Stendel, Peter Langen, Danish Meteorological Institute

This is a misleading statement, as “extremely thin” is not defined and what is also not stated is that there were also substantial areas of much thicker ice in 2008. If we look at the total ice volume, which averages these effects out, on 1st May 2017 it was about 6% lower than the ice volume for the same date in 2008 according to the operational ocean and sea ice model. Again, in addition to air and ocean temperature, ice thickness depends on winds and ocean currents and shows large variations from year to year so choosing two years arbitrarily is misleading without considering the long term trend.

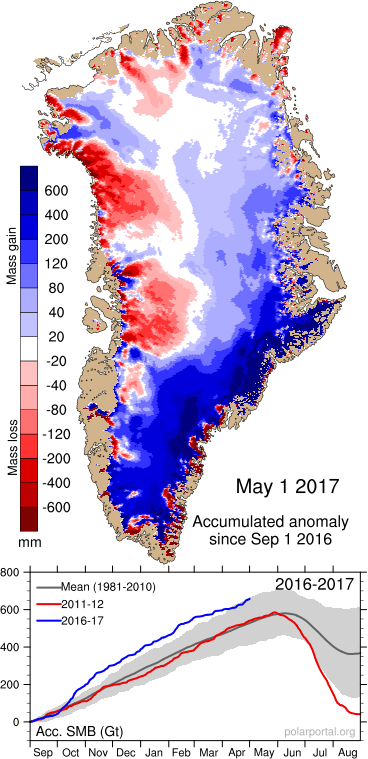

“The Greenland ice cap last winter increased in volume faster than at any time for years.”

Jan Lenaerts, Assistant Professor, University of Colorado, Boulder:

This is not per se completely incorrect, but the author does not tell us the whole story. The author refers to the growing of the ice sheet volume through snowfall throughout winter. The snow accumulated on Greenland in past winter (September-April) has indeed been remarkably high:

However, this does not imply that the volume of the ice sheet is increasing, because (1) the ice sheet also loses ice through discharging icebergs; it is the difference between snowfall-driven growth and solid ice discharge that determines if the ice sheet gains or loses volume, and (2) the snow that accumulated during the winter will (at least partly) melt over the summer. That’s why we analyse changes to the ice sheet volume/mass on (at least) annual time scales. Only after the summer we will know how much of the accumulated snow has (not) been melted.

uring the past years, the amount of melting has been record-high, and much of snow that accumulated over the winter melted and ran off into the ocean. Concurrently, ice discharge continued, so the Greenland ice sheet LOST considerable volume. We will know in September how much the ice sheet has changed volume this year.

Two additional remarks:

(a) The word “faster” should not have been used here. We are not talking about the rate of speed, but rather about the total change in volume. Also, it is easier to talk about “mass changes” than “volume changes” since the former is not sensitive to the density of the medium we are talking about (snow has a lower density than ice!).

(b) The enhanced snowfall, ironically, is most probably also a signal of the strongly warming Arctic: as the atmosphere warms, it contains more moisture, and generates more precipitation. Also, record-low fall and winter sea ice extent led to large streaks of open water that might have contributed to additional moisture loading of the air.

Here the author confuses short-term variability (i.e., weather) with a significant change to the Greenland ice sheet. Until a full annual cycle is considered, it is impossible to say if the volume is increasing or not. We can confirm that there has been a record amount of snow and rain over Greenland this winter, most of it fell in October due to extra-tropical hurricane Nicole. However this “extra” winter snowfall is not yet part of the Greenland ice sheet but a snow layer sitting on top of it and the extra gain in snow may be easily wiped out by a warm sunny summer. The summer is by far the most important time of year for the ice sheet—it determines if the ice sheet will grow or shrink so we will not know until September if this winter’s extra snow will have any effect on the overall ice sheet mass budget. Furthermore, we should bear in mind that extra snowfall in Greenland is actually predicted in most climate models, (a warmer atmosphere = more moisture = more snowfall in Greenland) as a consequence of climate change. We should also note that almost all of the additional above average snow fell in the East and South, and north-western Greenland actually has less snow than usual (which you can see in the figure above).